An Urban's Rural View

What Happens When People No Longer Answer the Phone

Everyone's talking about artificial intelligence (AI) -- and rightly so. About its risks, which are many and frightening. About its rewards, which are many and alluring.

Among the rewards, AI has the potential to greatly expand mankind's ability to access information and turn it into knowledge. Yet as 2024 dawns, I find myself pondering the limits of the information and knowledge we already have.

The quality of the information we rely on seems to be declining. Our ability to interpret data or information and convert it into knowledge often seems questionable.

In 2023, the U.S. economy provided a disturbing example of our inability to interpret information accurately. As the year began, economists viewed with worry a variety of indicators, starting with rapidly rising interest rates and a slumping housing industry. To most analysts, the meaning of the data was clear: A recession was imminent.

It never came. And while it could still come in 2024, some of last year's pessimists now think the Federal Reserve may have pulled off a unicorn-like "soft landing." The S&P 500 ended the year up 24%.

When an economist's forecasts err -- and they often do -- there are, broadly speaking, two possible reasons. One is the design of the economist's model. Any model's equations incorporate assumptions about the importance of various indicators and the cause-and-effect relationships between indicators. Given the complexity of the economy and the nearly infinite number of possible surprises the future may deliver, it's a wonder economists' models occasionally come close to getting it right.

P[L1] D[0x0] M[300x250] OOP[F] ADUNIT[] T[]

The other cause of errors is GIGO -- garbage in, garbage out. The model can't come up with the right answer if the data, the information fed into the equations, is wrong. And the quality of the data is increasingly open to question.

In the agriculture world, there have long been complaints about the quality of the data, in particular USDA's reports on things like supply, demand and ending stocks. I don't question the integrity or competence of the people who put together these reports and I recognize the reports can move markets. Still, farmers and market analysts, including DTN analysts, often argue convincingly that reports are erroneous.

Fear that farmers were overly dependent on USDA reports was among the reasons DTN launched the DTN Six Factor Market Strategies nearly two decades ago. The Six Factors use data from the markets rather than the government to analyze where prices are headed and make buy-sell recommendations.

While the complaints about USDA reports go way back, non-agricultural government data has been hit with a different, more recent problem.

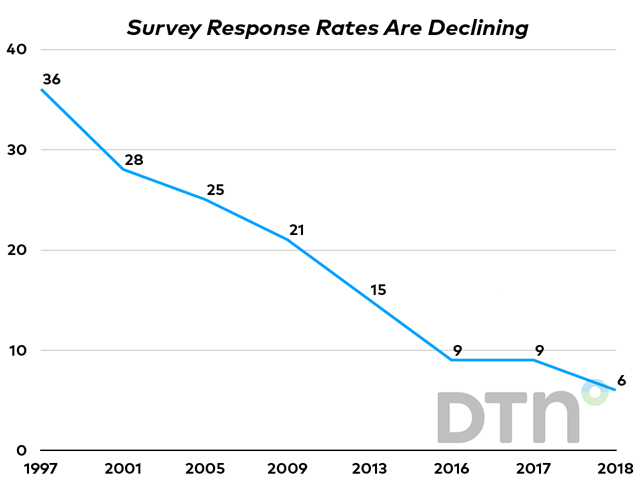

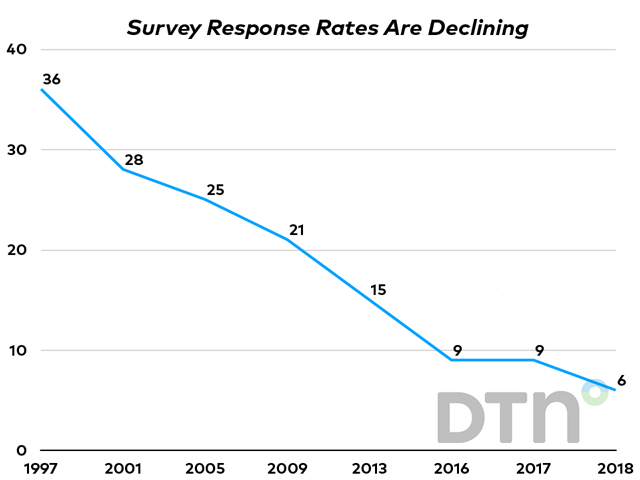

Some of the most important data comes from polling. But these days Americans are less and less likely to answer their phones or respond to requests to participate in written or electronic surveys. Response rates have been declining, sometimes dramatically. And while lower response rates don't automatically mean inaccurate results, they increase the risk of error.

COVID-19 made matters worse. Some government agencies, like the Bureau of Labor Statistics, collect some of their data through in-office visits with businesspeople. Owing to the pandemic, some of them are no longer in their offices. They work from home. The agency is scrambling to adjust. (https://www.bls.gov/…)

(Some people think the BLS's consumer price index, which showed rapidly declining inflation last year, must be flawed because prices of many things are higher than they were several years ago. But the CPI is comparing prices with last month and last year, not several years ago, so that's not a reason to think the CPI is off.)

Private pollsters have likewise seen response rates fall. Experts are still arguing about whether this decline was responsible for the missed calls in the 2016 and 2020 presidential elections, and if so to what extent.

What's known is that lower response rates have forced pollsters to wonder whether some kinds of voters are less likely to respond and are thus underrepresented in surveys. In 2020, for example, most polls predicted Biden would win but vastly overestimated his margin of victory. Could Trump voters have been underrepresented?

Most of the statisticians who devise polls, public and private, are smart folks who work hard to understand their mistakes and make adjustments. But getting the adjustments right is both difficult and expensive. Despite pollsters' best efforts, there's no guarantee they'll succeed.

This being an election year, you're going to see a lot of media reports of polls. Before taking the results too seriously, check out what the pollster says about how the survey was conducted, the margin of error and any compensatory adjustments to the sample. The best pollsters will divulge this information and more.

Could AI help pollsters improve their accuracy? Stay tuned.

Urban Lehner can be reached at urbanize@gmail.com

(c) Copyright 2024 DTN, LLC. All rights reserved.

Comments

To comment, please Log In or Join our Community .