Minding Ag's Business

CCC and Crop Insurance Backstop Farm Incomes But Could Face Challenging Future

Lower commodity prices and falling farm incomes took center stage at USDA's recent Agricultural Outlook Forum with the agency forecasting season-average corn and soybean prices of $4.40 and $11.20 per bushel, respectively.

Many farmers will be unable to turn a profit at those prices, which contributed significantly to USDA's projection that farm incomes will drop 25% from last year. Compared to 2022's record, farm incomes are expected to be nearly 45% lower when adjusted for inflation.

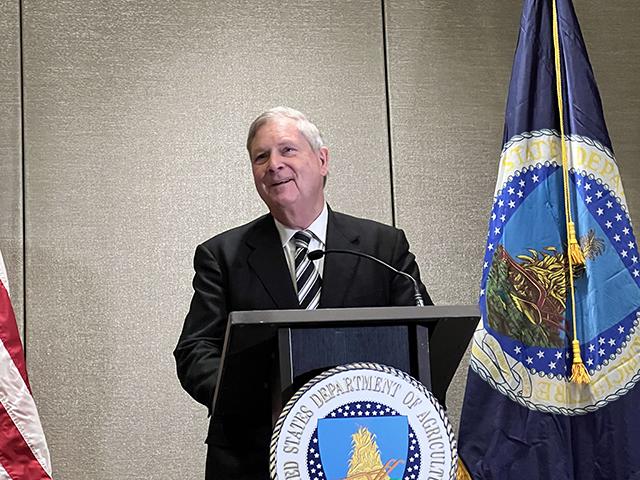

"First of all, it's not surprising that commodity prices are falling," Agriculture Secretary Tom Vilsack replied to a DTN question at a news conference during the event. "The past three years combined have been the best incomes in 50 years. I think what we're looking at potentially is probably incomes around relatively historic levels, getting back to sort of a normal pattern."

Nathan Kauffman, senior vice president of the Federal Reserve Bank of Kansas City, also urged the industry to think of 2024 incomes in long-term historical context.

"Yes, incomes are lower. Profit margins are tighter. Credit conditions are still strong but weakening a bit," he said. "If by chance we were to get another year -- maybe not 2024 but in 2025 -- where you see another reduction in farm income and a similar percentage decline in working capital, now we're starting to get into the territory that we were in agriculture between 2016 and 2019, and we know that those were not strong years."

It's why Vilsack then made the case for "more, new and better markets ... ways to generate more income from nontraditional sources," such as credits for sustainable agriculture practices.

But the secretary also leaned into using the Commodity Credit Corporation (CCC), pointing to USDA's recent purchase of $100 million of pork, to support producers. He touted the expansion of crop insurance as important support for the farm economy, noting that USDA has released 12 new policies and 15 modifications in the last three years.

"If you look at the history of RMA (Risk Management Agency), over the course of the last 20 years or so, there's been a rather dramatic increase in the number of policies sold, in the number of modifications and the number of varieties that are now covered that weren't covered in the past."

A panel of former USDA chief economists took issue with both of those and suggested that Congress may need to reign in the popular programs as the federal deficit climbs.

Robert Thompson, who served as USDA assistant secretary of economics from 1985-87, advocated most strongly for Congress passing new limitations on the use of the CCC.

P[L1] D[0x0] M[300x250] OOP[F] ADUNIT[] T[]

"The CCC is simply a license to steal," he said. He added that Congress would never approve its creation today because it essentially amounts to giving an agency "a blank check or line of credit at the Treasury. You don't have appropriated funds up front and you just go press the replenish button on your checking account when you spend it down. You couldn't create it if you wanted to."

Rob Johansson, who served as USDA chief economist from 2014-20, disputed the notion that the CCC is a blank check and said it allowed USDA to respond quickly to events outside of the purview of the farm bill, like the trade war with China and the pandemic. USDA's Market Facilitation Program payments in 2018 and 2019 were intended to offset the impact of reduced trade with China, and in 2020, the payments accounted for 39% of net farm income.

Johansson said that by comparison, the congressional appropriations process is slow.

Whether it's slow or not, Joe Glauber, who served as USDA chief economist from 2008-2014, said Congress needs to put more controls on the use of CCC. "If they want a supplemental bill or whatever, make them pass it."

While Vilsack touted the expansion of crop insurance programs over recent years to cover more producers and more crops, the group of economists raised warning flags over the additional costs of the program. Typically, USDA subsidizes farmers' premiums around 60%, and as insured liabilities go up, so does the government's outlay. According to the Congressional Budget Office, premium subsidies cost nearly $12 billion in 2023.

"I think I've spent most of my career writing about crop insurance, and every time I turn around, it's grown a few billion dollars in premium volume," Glauber said.

The economists generally made two arguments. First, many producers could accomplish the same risk protection goals using non-subsidized options markets, and second, the program has grown beyond insurance into pure price support.

The popularity of livestock insurance programs has boomed in recent years, and Johansson said that with no caps on the size of producers that can enroll in the programs, "you can get aggregators out there that are going to cause problems."

Dan Sumner, who served as USDA Assistant Secretary of Economics from 1992-93, was the most direct.

"It's not insurance, it's a subsidy program and let's just call it that," he said. "A dollar invested in crop insurance, on average, gets you back a couple of bucks. So that's a better investment than almost anything I know."

The expansion of crop insurance to try to serve the broader industry, and not just a few select commodity crops, is a part of the problem. As a professor at the University of California-Davis, he highlighted the expansion of the program into the wine grape industry. Prices for grapes can vary as much as 1,000% from one county to the next, depending on the variety.

"There's no way an insurance company would ever deal with that," he said. "And yet, these so-called specialty crops are pretty big industries, so I don't know how you justify not covering them given that you're going to cover everything else including livestock."

Glauber said the popularity of the crop insurance program makes it a particularly sensitive topic with farmers. "To me, I think it's time to start trimming back subsidies to some of these programs and really questioning why we're insuring price when there are private instruments available."

Thompson said agriculture's hand could be forced by the ballooning federal deficit. "I think in the next five to 10 years, agriculture may actually have to decide how to weed out redundancies between the commodity support programs and the crop insurance programs."

Also see:

"USDA Outlook: Growing Supplies, Lower Prices in First Look at 2024-25 Crops" https://www.dtnpf.com/…

"USDA Expects Farm Profits to Fall 25% in 2024"

"Vilsack Says CCC Fund Offers a Creative Solution to Raise Reference Prices in Farm Bill" https://www.dtnpf.com/…

Katie Dehlinger can be reached at katie.dehlinger@dtn.com.

Follow her on X, formerly known as Twitter, at @KatieD_DTN.

(c) Copyright 2024 DTN, LLC. All rights reserved.

Comments

To comment, please Log In or Join our Community .