An Urban's Rural View

There's Good News and Bad News About Interest Rates

The question for interest rates is no longer how high they'll go but how long they'll linger around current high levels before coming down.

At its latest meeting, which ended Nov. 1, the Fed held its benchmark interest rate steady in the range of 5.25% to 5.5% for the second meeting in a row following 11 consecutive increases. (Average borrowers' rates move higher with the Fed's benchmark; the 30-year-mortgage fixed rate recently hit 8%.)

While Fed chair Jerome Powell held open the possibility of another increase at a future meeting, many analysts think any such increase would be small. Others think the Fed is done raising. There's an emerging consensus that rates have peaked, or nearly so.

There's less consensus on how long before rates come down, partly because analysts are divided on the outlook for the economy. Many bond investors have been thinking the answer is, "longer than we previously expected." Goldman Sachs is telling clients it doesn't see the Fed cutting rates until the end of next year.

Expecting short-term rates to remain high longer, bond investors have been demanding higher yields to compensate for what they perceive as an increase in the risk of holding long-term debt. The yield on the 10-year Treasury note recently hit 5%, though it has come down a bit since.

Investors could be wrong, of course, or forced by changing economic and financial conditions to reconsider. So, it's worth taking a look at what Federal Reserve policy makers themselves foresee.

P[L1] D[0x0] M[300x250] OOP[F] ADUNIT[] T[]

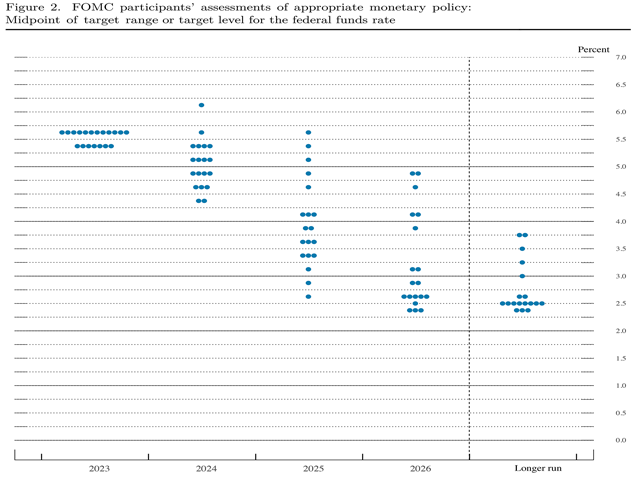

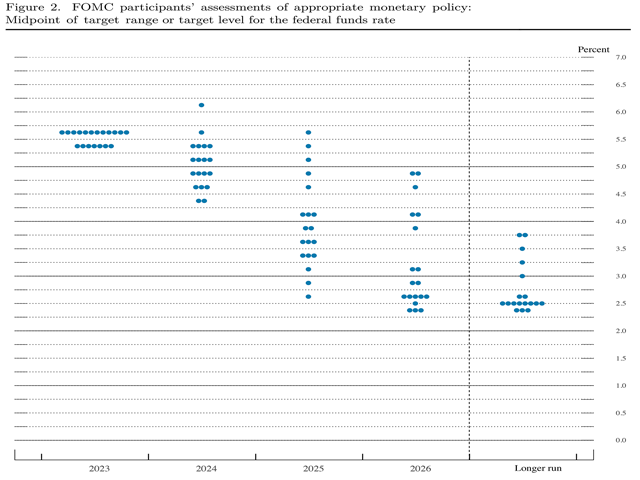

We can do that by reviewing the so-called "dot plot" that the Fed releases each quarter. It reflects the views of the 19 members of the Federal Open Market Committee, often shorthanded the FOMC or "the Fed." These are the policymakers who set monetary policy and interest rates.

Seven of the 19 are senate-confirmed governors of the Federal Reserve Board. The others are presidents of the 12 independent regional Federal Reserve banks. At any given time only 12 of the 19 vote -- the seven governors and five of the presidents. (Four of the five rotate annually; the New York president always votes.) All 19 take part in the meetings and the dot plot shows their interest-rate projections for the next three years and longer run.

In the latest dot plot, issued in September, 10 of the 19 see the Fed's benchmark rate above 5% at the end of 2024 and 17 see it above 4.5%. (https://www.federalreserve.gov/…). They're predicting rates will remain near current levels for another year, at least.

By the end of 2025, 12 of the 19 project a benchmark rate in the 3s to low 4s. Only by the end of 2026 do we get majority support for the 2s.

The good news for farmers ranchers and other business borrowers: Only one FOMC member sees the Fed's benchmark rate above 5.5% for the next three years.

Uncertainty about inflation is what's keeping the projections near recent highs. After its latest meeting, Fed chair Jerome Powell said the FOMC won't lower rates until it's convinced the inflation rate is on a sustainable path to 2%. We're a long way from 2% inflation, he said.

Of course, the FOMC members could be wrong, too. These dots are essentially forecasts. They change from meeting to meeting. And while the people making them know more than the average citizen about these things, no one has an infallible crystal ball.

You might wonder, then, is there anything that could happen that would render the consensus wrong and bring rates down earlier?

A recession might. So far the Fed seems to have engineered a "soft landing" for the economy but some analysts still see a hard landing and a recession ahead. Should those analysts be proven right, the Fed would come under intense pressure to lower rates. If the recession brought inflation down, a Fed decision to cut would be relatively easy. (A recession combined with stubborn inflation would be a nightmare for the Fed.)

There is another way for the consensus to be wrong and this way would be worse for business borrowers: Inflation could leap again.

Continuing war in the Middle East and Ukraine could send prices soaring. Inflation might also reignite if lots of other labor unions match the hefty wage increases the Teamsters and United Auto Workers and Air Line Pilots recently won. (Overall, though, wage increases have been coming down lately.)

Should inflation head north again, all bets are off; the Fed would almost certainly raise rates. But while surging inflation is imaginable, it's not the most likely outcome. For now and probably for some months to come, the question really is not how high, but how long.

Urban Lehner can be reached at urbanize@gmail.com

(c) Copyright 2023 DTN, LLC. All rights reserved.

Comments

To comment, please Log In or Join our Community .