An Urban's Rural View

No Longer the Arsenal of Democracy

The industrial revolution began in Britain in the late 18th century and came to the United States in the 19th. By the beginning of the 20th, the U.S. was the world's leading industrial nation. It remained No. 1 until 2010, when it was surpassed by China. (https://www.aei.org/…)

Today the U.S. and China are geopolitical rivals. Neither side wants rivalry to devolve into war, but both sides' militaries have to plan for that possibility. That's why China's rise as a manufacturing powerhouse and America's relative decline raise troubling questions.

Manufacturing might can win wars. The North's industrial base played an important role in its victory over the South in the U.S. Civil War. America's vastly larger industrial base was decisive in World War II. President Franklin D. Roosevelt rightly called the U.S. the "Arsenal of Democracy."

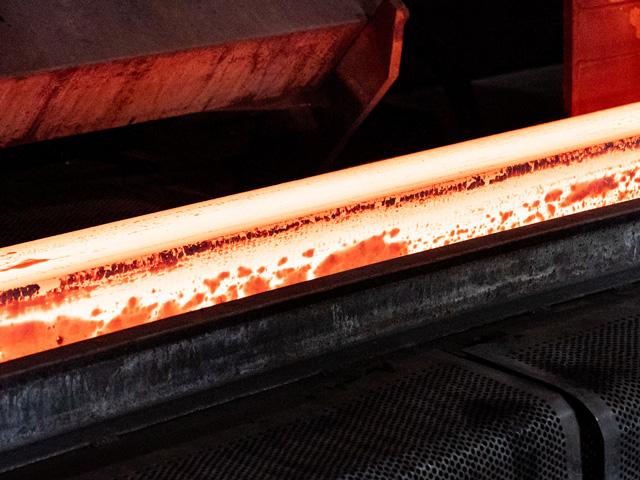

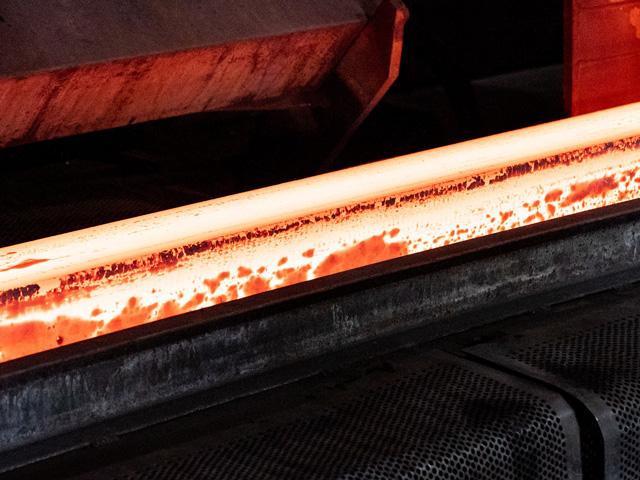

In the late 1940s, in that war's aftermath, the U.S. was producing more than half of the world's steel. Today, China produces half of the world steel. U.S. steel output is less than a tenth of China's.

And it isn't just steel; the U.S. and China have traded places in the manufacture of many other critical products. Should, God forbid, the U.S. and China ever become engaged in a lengthy war, China would replace depleted weapons supplies faster. According to a retired Air Force general, war games show that in a war with China over Taiwan, "We run out of munitions in the first week."

Indeed, the U.S. industrial base's limits are already being tested as the Russian invasion of Ukraine coincides with fears of a Chinese attack on Taiwan. Supplying Ukraine with the weapons it needs to defend itself is taxing the U.S., while the backlog of arms shipments to Taiwan has swelled to $19 billion. (https://www.nytimes.com/…)

According to the retired general, "Ukraine uses 20,000 rounds of artillery a day. We produce 20,000 rounds a month."

P[L1] D[0x0] M[300x250] OOP[F] ADUNIT[] T[]

U.S. industrial capacity, he says, "is a huge issue."

Two of the troubling questions arising from the U.S.-China industrial role reversal are why it happened and what to do about it.

An admittedly oversimplified answer to the why question is that U.S. post-World War II policies were based on economic logic rather than geopolitical logic. If we'd followed geopolitical logic, we'd have leaned over backward to protect our industrial base as a matter of national security even if it made our economy less efficient.

Economic logic offers lower prices and higher living standards through the free flow of goods and investment capital. In economic logic no country makes everything; nations produce the goods and services they can make competitively and trade for the rest. Financial markets allocate capital to the most profitable producers.

For many decades after World War II, economic logic yielded the prescribed economic benefits without undermining national security. The U.S. industrial base was strong enough to produce most of what was needed for national defense.

Two things have changed. In recent decades, economic logic took American companies beyond manufacturing overseas for overseas markets to manufacturing overseas for the American market. Worse, the "offshored" factories went heavily to China, a country that has gradually emerged as a geopolitical rival.

It's uncomfortable depending on a rival for vital products. American companies are increasingly "reshoring" (returning manufacturing to the U.S.) or "friend-shoring" (moving China manufacturing to friendlier countries) instead. Uncle Sam is promoting reshoring, offering financial incentives to build things like semiconductors and electric cars in the U.S. and imposing Buy-American requirements.

So far, reshoring and friend-shoring are the main answers to the what-to-do-about-it question. But these are random efforts. There's no strategy underlying them. We're sleepwalking into industrial policy.

Switching to geopolitical logic and industrial policy has risks. If we're not careful we could blunder by propping up parts of our industrial base that don't need propping up. Worse, we could fail to back the development of industries that are small now but will be critical in the future.

A strategy would minimize those risks.

What's needed is a national commission to study the industrial base and recommend a way forward. It should include Republicans and Democrats, businesspeople and labor leaders, economists and national-security experts. It should have a staff and a budget that's up to the task.

Farmers and ranchers need to stay on top of the industrial-base issue. Agricultural prosperity depends on trade and industrial policy affects trade policy. Trade partners hurt by Buy-America policies may retaliate with barriers to U.S. exports.

And just as the U.S. is increasingly wary of dependence on China, China is increasingly wary of dependence on the U.S. We still sell China soybeans but we're no longer the preferred supplier.

The U.S. must have an adequate industrial base. Hopefully it doesn't come at the expense of ag exports.

Urban Lehner can be reached at urbanize@gmail.com

(c) Copyright 2022 DTN, LLC. All rights reserved.

Comments

To comment, please Log In or Join our Community .