Ag Weather Forum

Why Do Weather Models Change Dramatically Sometimes?

If you have been looking at your forecast for Thanksgiving during the last week, it has likely changed several times, especially when it comes to precipitation timing or amounts -- but why?

First, here's the latest forecast as of Nov. 23, written by Teresa Deutchman, a meteorologist with DTN, that gives more details about drought relief coming to the Southern Plains on Thanksgiving Day: https://www.dtnpf.com/….

Now, back to the discussion on why models can have changes.

Smaller disturbances that grow into larger ones are frequently mishandled by weather models. The results are sometimes wild forecast differences from run-to-run. Usually this happens with systems at time scales longer than a week out but can even happen to ones that are only a few days from forming.

An excellent example is what has happened during the last week. About a week ago, models were showing a very progressive pattern to take hold of the U.S. for the Thanksgiving week. This pattern usually allows for systems and disturbances to more freely move through without getting locked up or deepening significantly. Usually, the result is a weak or moderate-strength storm system that moves through rather rapidly.

The European Centre for Medium-Range Weather Forecast (ECMWF) was showing this pattern as was the American Global Forecast System (GFS). Both the regular runs and ensemble of runs showed this likelihood, though they disagreed on timing and development and other such details that usually accompany a medium-range forecast. Both seemed to indicate a chance for some sort of storm system around the Wednesday-through-Friday time frame of this current week.

P[L1] D[0x0] M[300x250] OOP[F] ADUNIT[] T[]

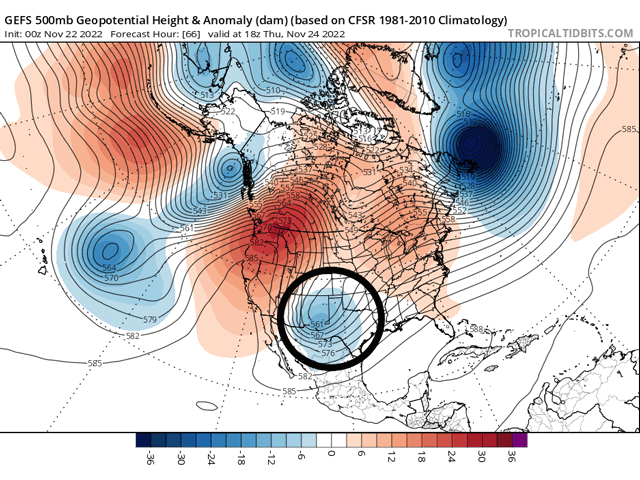

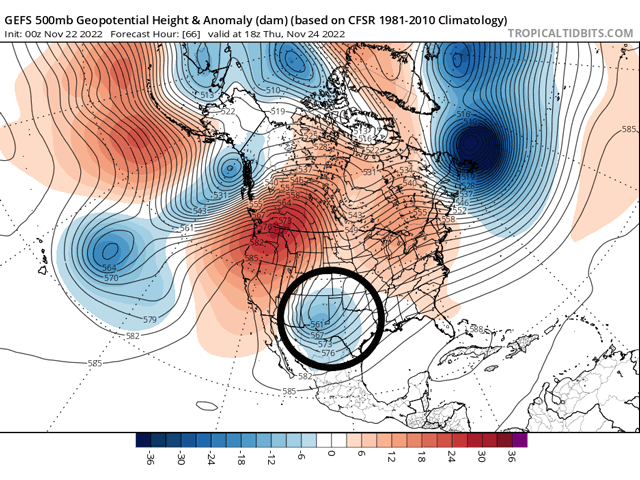

During the weekend, the two models diverged significantly. The ECMWF kept the same progressive pattern, but the GFS made a significant change. Instead of a progressive system that moved through quickly around Thanksgiving, the model produced a cutoff low across the Southern Plains with a ridge over the top of it. These sorts of setups usually cause the low to linger in an area, or at least move much slower.

The result was a difference of about 36 hours between where the ECMWF had the low-pressure center, and where the GFS did. That was for a storm system that was expected to form just three days ahead of time. That meant the difference between having heavy rain in Texas, or in the Midwest between the different models at the same time, on the morning of Thanksgiving.

The two models have since come into alignment and it appears that the GFS, who was first to grab onto the possibility for an upper-level cutoff low instead of a progressive one, appears to be more correct.

So what was causing the difference? It was mostly the strength and position of the small disturbance which is now heading into British Columbia and Washington state. It has been hard to gauge in a conglomeration of disturbances and upper-air features over the Pacific Ocean for the last few days. With mostly just satellite data confirming its presence and position, models have had a tough time trying to latch on to such a small feature.

We should feel lucky here in the U.S. Say what you will about the government, but the amount of data that this country produces and provides for free is truly incredible, and a good reason why forecasts for the U.S. are usually pretty good at such good length.

However, weather data over the rest of the world is much harder to come by and often incomplete. Surface observations can be hundreds of miles apart or the data could be behind certain government blockades. Some governments are better than others at providing data and producing good observations.

Where we do not have good data from is over the oceans. Ships, buoys, and airplanes exist but at much less density than over land. Satellite data fills in the gaps, but is not perfect or precise. There are errors using these data. The U.S. has better satellites over the northern Pacific and Atlantic, but there are gaps in other spots of the world. Therefore, errors in data or missing data could lead to large errors in the look of the atmosphere to the models. And each model handles these items differently. There are just a lot of ways that models can look different -- both between themselves and between others.

To combat this, especially at long range, looking at more than one model is preferred. You can run the same model dozens of times in a row while making some small tweaks to arrive at different solutions. By averaging them all out, you can usually get a better idea of what sort of pattern is evolving through the noise. That is called an ensemble. This method is preferred at scales longer than about a week because each individual model run's errors compound over time and some can produce solutions that just do not make sense.

However, by using ensemble forecasts, details are often left out, especially small ones like the disturbance that will cause a storm system across the U.S. this week. Large-scale patterns are usually forecast well, but details and smaller disturbances often missed, which sometimes lead to large variations in the expected weather, and especially with precipitation.

For those of you now in the path of the Thanksgiving system, I hope that the weather does not reduce your Thanksgiving holiday festivities. If you are not, enjoy your day or weekend or however you choose to celebrate and give thanks.

**

Join me for the 2022 DTN Virtual Ag Summit Dec. 12-13 where I will talk about the weather patterns and conditions expected for the 2023 growing season. Get all of the information you expect from DTN, from the comfort of your home or office! For details on the agenda and how to register, visit www.dtn.com/agsummit.

John Baranick can be reached at john.barnick@dtn.com

(c) Copyright 2022 DTN, LLC. All rights reserved.

Comments

To comment, please Log In or Join our Community .