Fundamentally Speaking

Relation Between U.S. Dollar & CME grain markets

With the surge in foreign exchange value of the dollar based off Friday's impressive jobs figures, the U.S. Dollar index has now moved to 12 year highs and has decisively broken past the long-term downtrend line drawn off the 1982 and 2000 highs.

Most commodities around the world are traded in dollars and a higher valued greenback is inherently bearish to commodities.

While the paradigm shift higher in grain and oilseed prices starting in the fall of 2006 has been linked to the renewable fuels boom and increased meat and dairy consumption in the developing world necessitating increased usage of feed grains and high protein meals, the protracted depreciation of the dollar's value was also a key factor.

P[L1] D[0x0] M[300x250] OOP[F] ADUNIT[] T[]

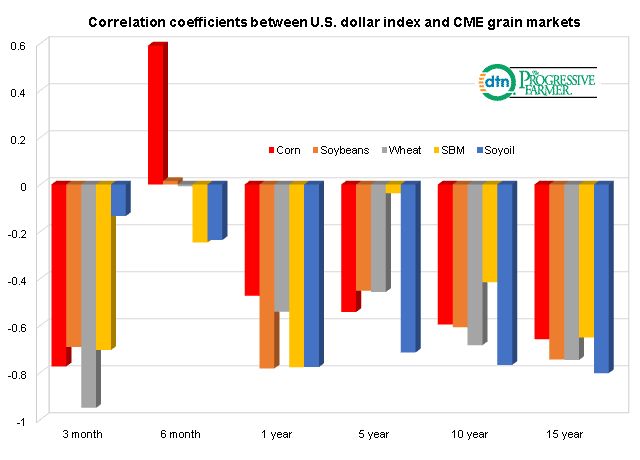

To test the impact of dollar movements on certain agricultural commodities we ran the correlation coefficients of the U.S. dollar index vs. a number of markets for a period of three months and six months along with one year, five, ten and fifteen year intervals.

Note that two markets that have a strong positive correlation, that is when one increases in value the other market does so at the same percent has a figure of 1.00, whereas two markets that are completely inversely correlated where a movement of one is offset by an equal move in the opposite direction has a reading of -1.00.

Two markets that are uncorrelated where movements in one have no influence on the other have a reading of zero or close to that.

A correlation greater than 0.8 is generally described as strong, whereas a correlation less than 0.5 is generally described as weak.

A look at the data shows with the exception of the six month period for corn and soybeans, all the correlation coefficients for these two markets along with soybean oil, soybean meal and wheat are inversely correlated.

There appears to be a fairly strong correlation with most of the markets, particularly wheat as the large numbers of importers and exporters make that the most global of commodities.

Suffice to say that even with the strong dollar depressing almost all commodities, the impact on the grain and oilseeds is even more acute as foreign supplies are more than ample and the rallying dollar making our prices even less competitive in the world markets.

(KA)

Comments

To comment, please Log In or Join our Community .