Editors' Notebook

Eagles and Expectations: 50 Years of the Endangered Species Act

JEFFERSON CITY, Mo. (DTN) -- When I was kid, catching a glimpse of a bald eagle was always a thrill. Why? Well, it simply didn't happen all that often.

I grew up on a farm in Illinois near the Quad Cities, a region where the mighty Mississippi River uniquely flows from east to west. My best opportunity to see our feathered national symbol typically occurred during this time of the year -- when Old Man Winter tightens his grip on the Upper Midwest. As ice choked the rivers and covered the lakes to the north, the bald eagles that did exist would venture south in search of open waters on which to hunt. Occasionally, we'd see one.

Like so many elementary schoolchildren in the 1980s, I learned about the bald eagle's plight. While there were many factors, the bird's precipitous population decline was largely blamed on DDT, an insecticide. The chemical made the eagle's eggshells so thin and brittle that they'd crush under the weight of an adult bird tending to them in the nest.

The result? No eggs. No eggs, no eagles. The future appeared dreadfully bleak for the species.

But then my classmates and I learned that thanks to conservation efforts, the banning of DDT and protections provided under the Endangered Species Act (ESA), the story of the bald eagle was headed for an ending befitting a Walt Disney movie. The species' recovery was underway. Bald eagle numbers were increasing, and so would my opportunities to see them.

By the time I graduated high school in the mid-1990s, the bird's status had improved from "endangered" to "threatened." By the time my son was born in 2008, the bald eagle was no longer listed at all. Last week when I picked him up from high school basketball practice here in central Missouri, I saw four bald eagles along my drive.

P[L1] D[0x0] M[300x250] OOP[F] ADUNIT[] T[]

It was -- and truly still is -- a success story.

Today marks the ESA's 50th anniversary. It's the primary U.S. law for protecting imperiled species from extinction -- the law that gave the bald eagle back its wings, so to speak.

Signed by President Richard Nixon on Dec. 28, 1973, the legislation, along with the previously passed Clean Air Act and Clean Water Act, completed a trifecta of what many consider the most important environmental laws ever enacted in this country.

It would be an understatement to say that the ESA had bipartisan support in 1973. It received unanimous approval in the U.S. Senate, including "yea" votes from historically notable Sens. Bob Dole, Strom Thurmond, Ted Kennedy and then-first-term Sen. Joe Biden. It passed the U.S. House with a 390-12 vote. However, like so many pieces of federal legislation, what seemed straightforward at the onset became more complicated as five decades rolled along.

Yes, when the ESA was first being debated, it was easy to vote for protections for "charismatic megafauna" such as the polar bear, grey wolf, humpback whale, California condor and bald eagle. But as the list grew with the inclusion of lesser-known species that curtailed business and economic activity, the legislation earned more critics. Perhaps no species' protection gained more notoriety than the northern spotted owl in 1990, which pitted environmentalists against the interests of loggers. More than 30 years later, that debate continues.

Presently, a total of 1,668 plant and animal species in the United States are listed as threatened or endangered by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (USFWS). Another 65 species are proposed for listing. Most Americans have never heard of creatures such as the dusky gopher frog, thick-billed parrot or diamond darter (that's a fish), or plants such as pondberry, whorled sunflower or snakeroot. However, all these species and the places they reside, known as "designated critical habitat," are afforded protection under the ESA.

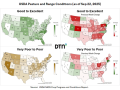

In agriculture, the law has come under heightened scrutiny in recent years as it pertains to the registration and use of pesticides that allow farmers to control weeds, insects and plant diseases that threaten their crops. The Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), the governmental entity tasked with registering these pesticides under the Federal Insecticide, Fungicide and Rodenticide Act (FIFRA), has publicly acknowledged that it hasn't completely fulfilled its ESA obligations for decades. This has left the agency vulnerable to lawsuits, leading to EPA's most recent attempts to come into compliance while still affording farmers with the ability to continue to use pesticides. Read more here: https://www.dtnpf.com/….

Despite the ongoing saga, the USFWS credits the ESA with saving 99% of the species it protects from extinction. But has the legislation really improved those species' overall prospects for continued existence? In 50 years, fewer than 50 species have been delisted due to recovery. Do these creatures simply require more time, or has the ESA only served to prolong their ultimate demise?

It's impossible to say definitively. Voluntary conservation efforts by those in agriculture during the past 40 years have certainly helped to keep some species from joining the list, and such efforts should continue to be encouraged. Farmers are just now beginning to harness the power of microbes, "aka biologicals," to improve their productivity. Imagine if these bacteria had been rendered extinct before their worth had ever been realized.

More than a generation ago, folk singer-songwriter Joni Mitchell opined that "they paved paradise and put up a parking lot." Yet the bald eagle provides an example of what's attainable when an entire nation rallies behind a species and does what is necessary to ensure its future.

Can such collective effort be the national expectation for all endangered creatures? Perhaps, but for these endeavors to be successful, they must conjure the same feelings of duty in the next generation that led to the creation of the landmark law a half-century ago.

Joni sang "that you don't know what you've got 'til it's gone." Watching bald eagles soar today certainly doesn't thrill my son the same way that it thrills me, but he's never lived in a world where the bird's existence was ever in question.

Jason Jenkins can be reached at jason.jenkins@dtn.com

Follow him on X, formerly known as Twitter, @JasonJenkinsDTN

(c) Copyright 2023 DTN, LLC. All rights reserved.

Comments

To comment, please Log In or Join our Community .