Ag Weather Forum

A Midwest Perspective on California Flooding

It may seem that the news of the latest round of atmospheric river-related flooding in California has nothing to do with the Midwest. After all, California is 2,000 miles and two or three time zones removed from the central United States. What happens weatherwise that far away has little to no impact on the commodity markets. Other than headlines, the reaction might be "So what?"

One possible answer lies in the response to this question: "Remember how bad the flooding was in 2019? Well, this is similar." And, indeed, it is.

USDA's weekly weather and crop bulletin for the week ending Feb. 4 notes that "February 1 contributed to daily-record rainfall totals in several locations, including Santa Barbara (2.93 inches), Los Angeles International Airport (2.49 inches), and Long Beach (2.45 inches)." And, just a few days later came another round of record precipitation that the bulletin highlighted. "Downtown Los Angeles experienced its tenth-wettest day since 1877, with 4.10 inches falling on February 4. Rainfall amounts for the 4th reached 2 to 4 inches or more in many other locations in central and southern California, including Van Nuys (4.30 inches), Santa Monica (3.46 inches), Santa Barbara (2.39 inches), Vacaville (2.35 inches), and Burbank (2.27 inches). Farther inland, Reno, Nevada, noted its highest daily snowfall total (8.5 inches) since December 31, 2022."

P[L1] D[0x0] M[300x250] OOP[F] ADUNIT[] T[]

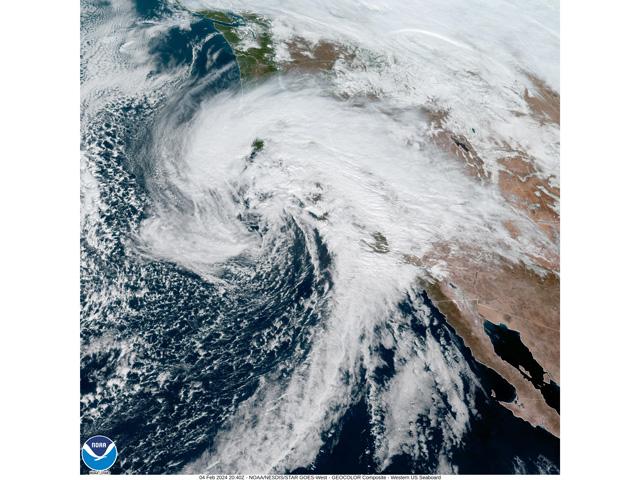

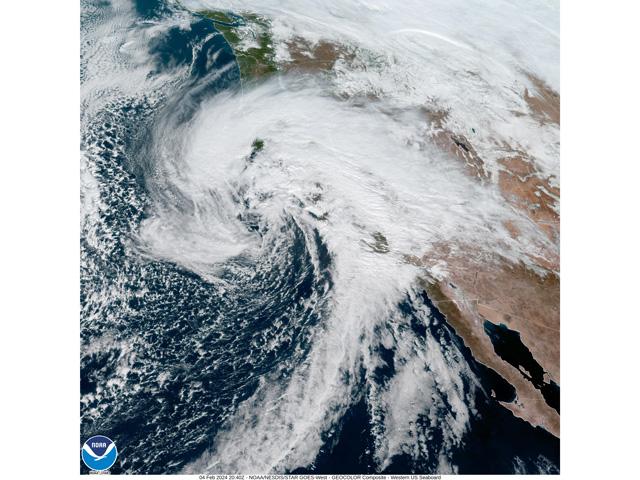

Weather elements in the California flooding of 2024 and the Midwest flooding in 2019 certainly exhibit a great deal of similarity. Both events had a deep center of low pressure positioned to draw in huge amounts of moisture from the sea. In California, the Pacific Ocean is the moisture source, with the driving low pressure center located to the north off the northern California/southern Oregon coast -- a definite atmospheric river. However, the Midwest had its own version of an atmospheric river five years ago; the flooding in 2019 had the Gulf of Mexico as the moisture source, with a deep low-pressure center located in eastern Colorado and western Kansas providing the channel for a tremendous surge of moisture. The 2019 storm reached bomb cyclone intensity, and the California storm either matched that intensity or came close.

California's varied terrain and soil type also contributed to the flooding. Most of the Midwest does not have the range of topography that we see in California with its mountains and valleys. In addition, the heavy rains fell on either desert soils or other soil types that do not have much organic matter or soil water holding capacity. These soil factors create runoff more quickly for both those reasons. In a point of similarity, the early rounds of flooding in the Midwest five years ago, which took place in mid-March, developed when heavy rain fell on frozen soils that offered no chance for the rainfall to soak into the water table and led to extreme runoff.

California's flooding will take a long time to repair; and, in places where cliffs and hillsides were washed away, the impact will be longer lasting. In the Midwest as well, floods five years ago have extensively reshaped the terrain in some of the hardest-hit areas, along with damage to roads, bridges and cropland that took months -- along with billions of dollars -- to repair. That cost in time and money is a feature that both regions definitely have in common.

Two more important details on the California atmospheric river need to be mentioned. First, the chances for an event like this were increased because of the presence of El Nino in the Pacific Ocean. While atmospheric river-origin storms don't always happen with El Nino, the odds are increased. And second, the world is coming out of a year of record warmth in recorded history -- including in the world's oceans. Warmer oceans in this time of a changing climate also increase the chances of heavy precipitation events like we have seen in California this year, along with the Midwest flooding in 2019.

Bryce Anderson can be reached at Bryce.Anderson@dtn.com

(c) Copyright 2024 DTN, LLC. All rights reserved.

Comments

To comment, please Log In or Join our Community .