Ag Weather Forum

When Does the Active Early Spring Weather Pattern Change?

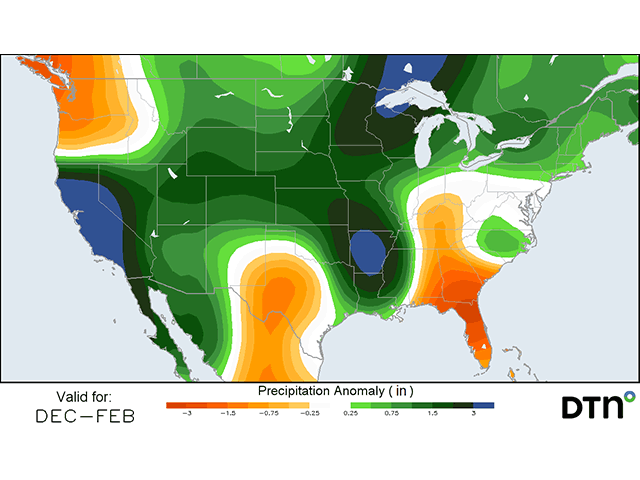

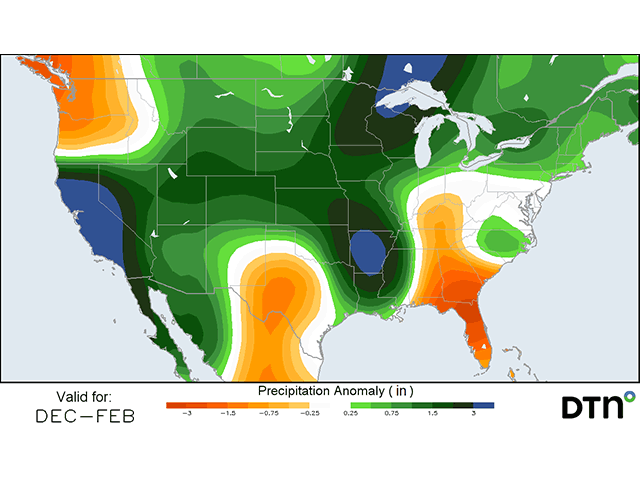

A storm system on Sunday brought severe thunderstorms to the Southern Plains as well as strong winds that kicked up dust storms in West Texas. But the storm started to affect the U.S. in California on Friday and dumped heavy precipitation there through the Southwest before doing so. That system is now in the Midwest where additional severe storms, heavy precipitation, and a wintry mix are occurring Monday, which translates to the Northeast Monday night and Tuesday. This is just the latest storm in a very active pattern over the course of the winter season.

I have found myself using the term "active" to describe the weather pattern for a long time. But what does it mean to be "active"? Essentially, it means the atmosphere continues to send pieces of energy across a given area, in our case North America, over a period of time. Two-to-three storm systems of varying intensity have been quite regular just about every week since November. Usually, one or maybe two storms would be expected during a given week. Getting multiples is rare. Getting multiples for months is even more rare. And there have not been many or any quiet weather weeks either, also very rare.

So, what is the culprit? Talking with the DTN long-range forecast team there are a lot of reasons why it has been an active winter.

One is the relative lack of large blocking features in the upper atmosphere, large ridges of high pressure. Like rocks in a stream, ridges divert air -- and storm systems -- around them and keep the areas underneath relatively quiet, weather-wise.

P[L1] D[0x0] M[300x250] OOP[F] ADUNIT[] T[]

We have seen plenty of ridges moving around North America this winter, including one being somewhat persistent in the Southeast or just off the coast. However, that ridge has not been strong enough to force the storm track farther north, and has aided in pumping additional moisture from the Gulf of Mexico northward for systems to use. What the ridge has done is keep the eastern half of the country quite warm this winter.

Meanwhile, there has been a more persistent trough in western North America. Troughs produce energy that creates storm systems. Being situated in the West, storms have had a fairly common track of developing around California, where heavy precipitation has reduced drought significantly, moving through the western states, redeveloping in the Plains, and then amplifying with the increased moisture from the Southeastern ridge as they move through the Ohio Valley.

Without the two together, the weather pattern would be much different. According to DTN Long-Range Risk Analyst Nathan Hamblin, "If you had a Southeast U.S. ridge without a big trough in the West, or if the trough was just in the Northwest with near/above normal heights in the Southwest, it would be a much drier outcome." The two together have been the reason for the active weather, but not the cause.

The Southeast ridge has been favored by the Madden-Julien Oscillation (MJO). I have mentioned it in this space before, but the MJO is a description of a zone of thunderstorms that travels along the equator regularly throughout the year. During the winter, when it is situated or stronger over the Maritime Continent region (the area that encompasses Indonesia, Malaysia, the Philippines, and the associated seas in between) and the western Pacific, there is a propensity for a ridge to develop in the Southeast as well. Such has largely been the case since November.

The other partner to the MJO is La Nina and its tendency to weaken the polar vortex. A weakened polar vortex breaks into pieces more easily, producing stronger troughs in the mid-latitudes. This has been a partial cause for the Western trough and the active weather pattern we have seen.

So, the question becomes: When do we break out of this active pattern? As soon as a Southeast ridge is no longer supported, the western trough will move east. The MJO is forecast to move eastward out of the Maritime continent region and through the Americas and eventually into Africa throughout the course of the next three weeks. Doing so will remove the Southeast ridge with time, likely during the middle of March. With the trough moving eastward, that brings another risk -- arctic cold temperatures east of the Rockies. While the storm track may cease to be active, it could get quite cold instead. The cold will start in western Canada next week and gradually fill in farther south through the middle of March. Thankfully, we'll be in the beginning of spring and the harshest potential for cold will be behind us. But we could still find ourselves with the need for heavier winter gear, including those in the Southeast U.S. that have not had to break them out very often this winter. Until then, through the next 10 to 14 days, the active pattern continues.

To find updated radar and analysis from DTN, head over to https://www.dtnpf.com/…

John Baranick can be reached at john.baranick@dtn.com

(c) Copyright 2023 DTN, LLC. All rights reserved.

Comments

To comment, please Log In or Join our Community .