Ag Weather Forum

Winter Weather Outlook for 2022-23 Shows La Nina in Control

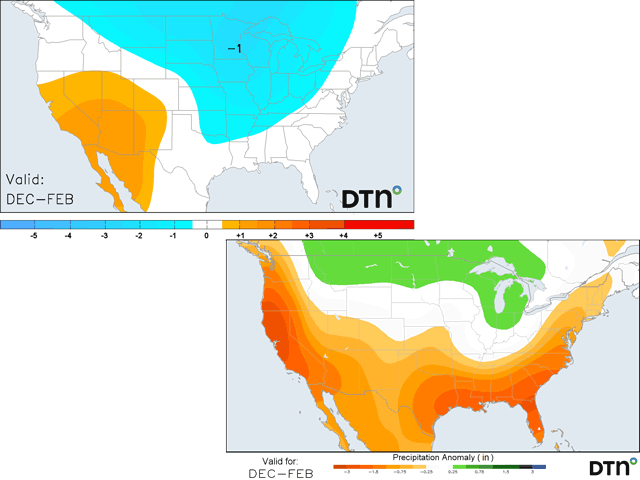

La Nina is headed toward control of its third-straight Northern Hemisphere winter season, though models forecast it to be closing toward neutral conditions late winter or early spring. Still, it takes the atmosphere some time to adjust to the newer conditions, keeping La Nina patterns in control going into the spring months.

The last two La Nina winters featured strong clipper patterns for much of the season and some incredible extremes. The upcoming winter is likely to display many of the same features but there are some differences that we might expect this year as opposed to the last two.

The biggest difference could be a colder December. As the DTN long-range forecasting team mentioned in a webinar released on Oct. 18, this coming December is showing some upper-level and tropical support for colder shots across much of the eastern two-thirds of the country. That is opposed to the last two years that have been well-above normal. In fact, most of the last decade has featured above-normal temperatures east of the Rockies in December; 2016 and 2017 had areas of colder conditions, but they were not widespread. The last year to feature a forecast somewhat similar to DTN's current forecast was Dec. 2013 or 2010.

However, this is a little situational and depends on the methods that DTN uses to forecast -- analog years. An analog is simply looking into the past to find years with similar conditions to the current year and using what happened in those past years to guide the forecast moving forward.

Several of the years that DTN uses in its analog composite point toward a colder December east of the Rockies and a warmer West. However, some of those were also quite the opposite. One significant source of temperature and precipitation variability is the location and intensity of clusters of thunderstorms that move across the tropics, known as the Madden-Julian Oscillation (MJO). In the years in which it was colder east of the Rockies, the thunderstorms were concentrated more over the central Pacific Ocean or the Americas. In the warmer years, those thunderstorms mostly hung out in the eastern Indian Ocean or what is referred to as the "Maritime Continent" -- the group of islands that compose Indonesia, Malaysia, and the Philippines. Our DTN forecasters are favoring the former, but note that if the MJO is farther west, December could turn out to be much warmer than their prediction.

P[L1] D[0x0] M[300x250] OOP[F] ADUNIT[] T[]

For their part, long-range models are somewhat mixed. The seasonal forecast from the European Centre for Medium-Range Weather Forecasting (ECMWF) indicates that December is likely to be above normal across the country. However, this model was last run on Oct. 1 and usually has trouble detecting cold air outbreaks far out into the future. It does much better with warmer patterns. However, it does note "less warm" conditions east of the Rockies than farther west, which is in line with the pattern the DTN forecast is showing. The American Climate Forecast System (CFS), which is run daily, looks much different. In the latest model run on Oct. 27, the model was calling for below-normal temperatures in Western Canada and above normal temperatures for most of the U.S. Previous runs during the last several days have been all over the place, anywhere from widespread cold to widespread warmth. In other words, the CFS does not have a consistent idea on how to treat the weather conditions in December. If that is the take-away from the model's forecasts, it would make sense for a La Nina winter -- lots of variability. And that variability is built into the DTN forecast for the rest of winter.

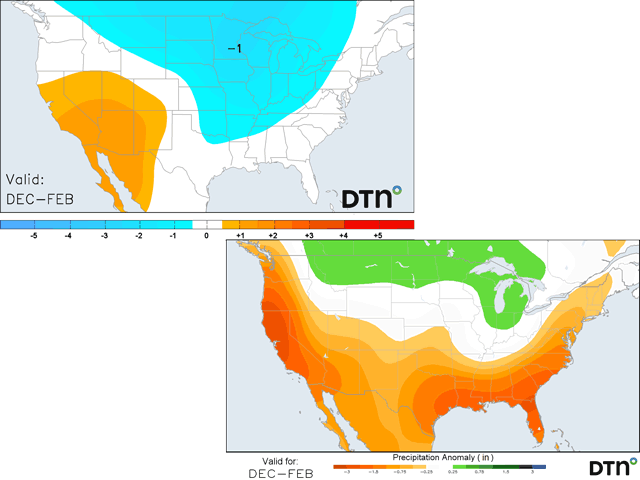

The months of January and February are likely to feature swings in the upper-air pattern, but more typically follow La Nina's tendency of frequent clippers moving from the Canadian Prairies into the Great Lakes and then arcing back up into eastern Canada. Such a storm track usually brings in periods of precipitation to the northern U.S. and southern Canada, but leaves the southern U.S dry. This also brings in lower temperatures to northern areas, but leaves the south warmer.

However, some of these storms could be more amplified, pushing colder temperatures and wintry precipitation farther south. The DTN long-range team noted in its webinar that La Nina years do provide some more extreme events during winter. We can all remember the extreme arctic blast that occurred in February 2021 and also the few that occurred in January and February 2022 that reached far to the south.

While the averages may point to warmer conditions across southern locations, these extreme events could muddy those averages and quickly change that to the cold side. Any of these strong pushes of cold air to the south would likely come with a storm system that could produce more wintry weather to southern areas.

So, there are higher risks of wintry weather for the Southern Plains and Southeast this year, even if total precipitation is lower than normal.

To recap, La Nina remains in control for the winter season, with waning influence in the spring. The DTN forecast follows a typical La Nina pattern for most of the winter season, which typically means a lot of clipper systems and bouts of cold air for northern areas while leaving the south warmer and drier. However, some of these systems could be strong, penetrating deeper south with increased risks for winter weather for southern areas. And unlike the previous several years, December has the greatest chance to come in with widespread below-normal temperatures east of the Rockies.

As far as impacts this might have for agriculture, river levels across the Mississippi River, which are at historical lows south of Cairo, Illinois, are likely to remain low going into the spring. Precipitation in the river basin does not look heavy enough to increase water levels in any significant way. Part of that is due to the heavier precipitation occurring in snowpack across the northern states. It will take until the spring melt for any areas to release their pent-up water. Even that may be too little as the tendency for above-normal precipitation is still low amounts during the winter months.

Drought areas across the Central and Southern Plains are likely to persist or grow, and expand across the Southeast as well. That will lead to more of a dependency on springtime precipitation for winter wheat coming out of dormancy.

Join me for the 2022 DTN Virtual Ag Summit Dec. 12-13 where I will talk about the winter weather outlook in more detail and what that means for agriculture going into the 2023 growing season. All of the information you expect from DTN, from the comfort of your home or office. For details on the agenda and how to register, visit www.dtn.com/agsummit.

John Baranick can be reached at john.baranick@dtn.com

(c) Copyright 2022 DTN, LLC. All rights reserved.

Comments

To comment, please Log In or Join our Community .