South America Calling

South America's El Nino Pattern Has Extremes in Dryness or Rain in Places

El Nino conditions are in place across the tropical Pacific Ocean and have been for a long time -- enough time that they have been able to affect global weather patterns and that certainly has been the case for South America.

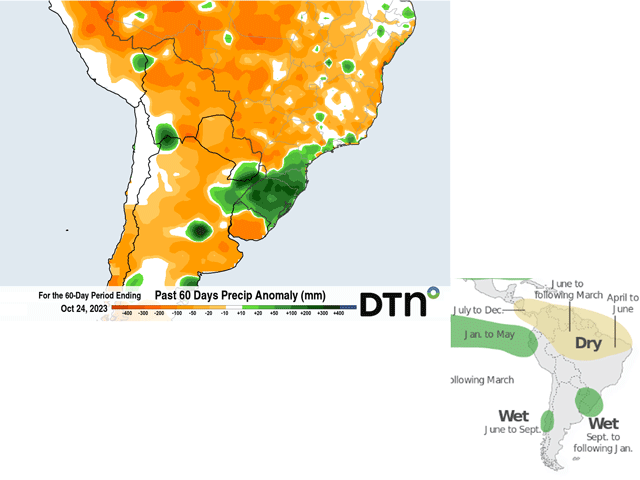

This has led to some extremes: Central and northern Brazil are seeing soaring temperatures and less rain than normal, while southern Brazil has seen flood damage and soaked fields.

So, what is happening and how much is this affecting South American crops?

Looking at data from NOAA here, https://origin.cpc.ncep.noaa.gov/…, El Nino conditions have been in place since the April-through-June timeframe. When looking more specifically at the coast of South America, those same conditions have been in place since early March. In other words, above-normal sea-surface temperatures have been in place for a long time. And the atmosphere has responded during the last couple of months, quicker than what it has over North America.

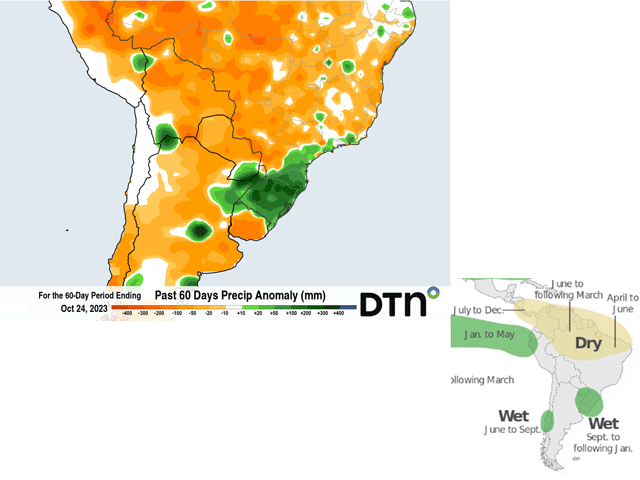

Typical rainfall patterns in South America under El Nino favor fronts moving through Argentina with relative frequency. This usually means decent rainfall in the country. Those fronts tend to stall in southern Brazil, leading to above-normal rainfall.

But these fronts mess with the normal circulations that bring daily rain to central and northern Brazil, causing more infrequent, or below-normal rainfall there. The pattern thus far has played out somewhat typically in that regard, but to the extreme.

During the last two months specifically, it has been very wet in southern Brazil. The state of Rio Grande do Sul has received more than 100 millimeters (mm) -- over 4 inches -- of extra rainfall than normal state-wide. Some areas of the state have seen more than 200 mm (over 8 inches) of extra rainfall.

P[L1] D[0x0] M[300x250] OOP[F] ADUNIT[] T[]

Rainfall records are being recorded for the month of October in some of these areas, which has led to flooding and quality damage to winter wheat, and difficulty with planting corn.

Soybeans are typically double cropped with wheat and the difficulty in getting that harvested is leading to delays in planting for soybeans. The heavy rain is filling some of these sandier soils though and where flooding has not been as much of an issue, soil moisture is more than abundant.

Nearby areas in Paraguay, far northeast Argentina, and occasionally the state of Parana have had issues with the heavy rain as well, but Rio Grande do Sul has been the target area during the last few months. The forecast through the end of November is for this trend to continue with excess rainfall being a concern for fieldwork and flood damage. It may be difficult to do any fieldwork and issues with pests and disease may arise as well.

It would stand to reason that Argentina would have benefited some from the frequent frontal passages, but moisture has just not been there when the fronts have gone through. Temperatures have swung quite a bit and late frosts have been frequent, especially in far southern growing areas, but the rain has been spotty at best.

During the last two months, only a small section of central Argentina got a dose of heavy rain. Otherwise, it has been very spotty and light. Below-normal rainfall and soil moisture are compounding problems from last season's historic drought for the country which caused huge reductions in crop production.

While rainfall has been disappointing for producers in Argentina so far, a nice blanket of showers this past weekend and early this week might have been the start to more favorable conditions going into the heart of the crop year. Long-range versions of the European ECMWF and American GFS point to near- or above-normal precipitation throughout the country's growing areas, good for getting corn back on track, and favoring soybean planting that starts up in November.

The conditions with the wet season showers in central Brazil have caused more concerns recently. Typically, El Nino leads to lower rainfall amounts in central and northern Brazil during the summer. Often, that is not much of an issue when these areas average 150-250 mm (6 to 10 inches) of rainfall each month during the heart of the wet season.

This year, wet season rains got an early boost in late August and early September when scattered areas of 25-50 mm (1 to 2 inches) of rain fell, a full month ahead of the typical start to the wet season. However, rainfall since then has been hard to come by. Many areas in the state of Mato Grosso, the largest production state for both corn and soybeans in Brazil, have seen less than 25 mm (around 1 inch) during the last 30 days.

Though wet season rains are only starting up, the state averages around 100 mm (about 4 inches) during that time.

Without much cloud cover or rainfall, temperatures have soared well-above normal, with many days near and above 40 degrees C (above 100 degrees F), which have put a harsh demand on early developing soybeans and will cause some areas to replant. Other areas of central Brazil have been luckier, with only slightly below-normal rainfall amounts during the last 60 days.

The forecast going forward varies in this area depending on the model. Most have below-normal precipitation, but still good amounts. Even the driest model, the American GFS, has rainfall amounts exceeding 100 mm for the month of November in Mato Grosso. However, this state averages closer to 200 mm or more, which may cause issues with heat stress when the rains are less frequent, even if the rainfall amounts would still be favorable for development.

Other than Mato Grosso, both the GFS and ECMWF favor near-normal rainfall, so any ill effects from recent dryness may be localized and short-lived for soybeans. However, these effects may make a bigger impact to safrinha (second-season) corn, which is immediately planted following the soybean harvest in late January and February. The safrinha corn relies on steady rains in the wet season to build soil moisture prior to the shut down of rain in early May. Should rains disappoint, there may be limited moisture for corn to draw upon when rains end, stunting yields. We still have a long way to go on that, but El Nino will be playing a large role in South America for another several months.

To find more international weather conditions and your local forecast from DTN, visit https://www.dtnpf.com/….

John Baranick can be reached at john.baranick@dtn.com

(c) Copyright 2023 DTN, LLC. All rights reserved.

Comments

To comment, please Log In or Join our Community .