Sort & Cull

Kub's Den: Under Which Circumstances Are Cows More Profitable Than Corn?

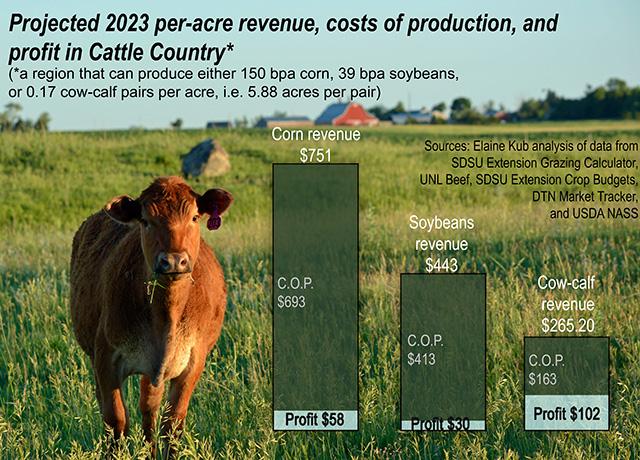

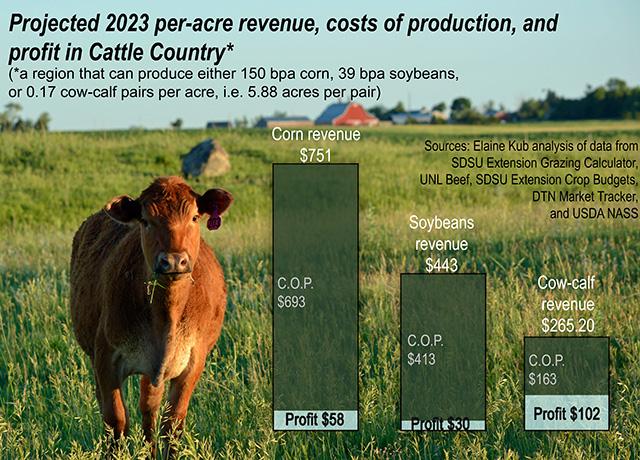

Projections for annual cow-calf returns to reach in the hundreds of dollars per head in 2023 and 2024 are enough to make a person sit up and start shopping around for heifers. But is it enough to make someone dig out their old seed drill and replant some quarters to grass? Recall how producers tore up sod and converted grassland to cropland during the ethanol boom of the late 2000s (https://www.pnas.org/…) -- is it time for the reverse to occur?

Steers coming through sale barns in Nebraska and South Dakota this month at about 600 pounds are reliably seeing prices above $260 per hundredweight, and the strong futures market through the end of this year suggests that by the time this spring's calf crop hits the sale barns later this year, they too can expect favorable prices.

For argument's sake, let's say each calf's value will be $1,560 (600 pounds times $2.60 per pound), but raising them requires $961 in annual cost per cow-calf pair, depending on various assumptions about ownership, interest costs, mineral programs, local grass leasing costs, etc.

That results in a very generous $599 annual profit per pair. Broken out per acre of production, the way corn or soybean budgets present their economic situations, this is equivalent to $101.83 in profit per acre, assuming we're looking at a region where it takes about 5.88 acres to stock each beef cow-calf pair for six months (0.17 pairs per acre, or about 27 pairs per standard 160-acre quarter-section pasture).

The density at which you can stock cattle on grassland varies greatly across the United States, from as few as 2 acres per beef cow in the Northeast and Lake States to sometimes as many as 50 acres per beef cow in the western Mountain states. Land values vary accordingly, so the profitability estimations made here shouldn't be considered representative of every cattle operation everywhere.

However, it's this "transitional" Cattle Country region that's particularly interesting (using 5.88 acres per pair), because this is characteristic of the places with a climate and soils that can justifiably go either way -- to crop production or pasture grazing.

For instance, think of places like Walworth County South Dakota on the east side of the Missouri River, for instance, or Sheridan County Nebraska with both farming and sandhills topography, or the rolling hills of Johnson County Missouri. These are all places where, depending on a given field's attributes, the land could be deployed either to stocking beef cattle at roughly this rate, or potentially growing 150 bushels per acre (bpa) of corn or 39 bpa of soybeans.

There is a broad swath of Cattle Country that has faced this choice over time -- to enlist the land into producing either crops or cattle. Should these fields grow corn on somewhat marginal ground, requiring investment in expensive machinery and inputs? Or should they grow beef animals on grass, requiring investment in barbed wire and labor?

It's finally this year -- when the cattle supply has been squeezed so low by drought -- that the math really starts to get interesting, because most crop prices also remain relatively favorable. Let's see how they stack up in this example region:

CORN

155.5 bpa at $4.83 new crop cash bid = $751.07 revenue this fall

P[L1] D[0x0] M[300x250] OOP[F] ADUNIT[] T[]

Minus $693.13 cost of production per acre

PROFIT: $57.94 per acre

**

SOYBEANS

38.6 bpa at $11.48 new crop cash bid = $443.13 revenue this fall

Minus $413.01 cost of production per acre

PROFIT: $30.12 per acre

**

SPRING WHEAT

63.4 bpa at $7.40 new crop cash bid = $469.16 revenue this summer

Minus $615.30 cost of production per acre

LOSS: -$146.14 per acre

**

COW-CALF PAIRS

0.17 pairs per acre at $1560 per calf = $265.20 revenue this fall

Minus $163.37 cost of production per acre

PROFIT: $101.83 per acre

**

Your mileage may vary, and all these assumptions require a lot of wiggle room for real-world productivity. They also don't necessarily represent reality for farmers in the I-states, where cattle operations may exist specifically to be an outlet for corn, or in the South, where prices may not be as high or drought may drive up forage values, or in the Mountain West, for that matter, where the alternative to pursue row crop production doesn't really make any sense.

Nevertheless, just about any way you slice it, cow-calf operators are, for once, in the nice position of actually being able to pencil out $100 or $200 or more in profit for each mama cow they care for. Not all grain producers can say the same for each acre they've planted in 2023.

**

Comments above are for educational purposes only and are not meant as specific trade recommendations. The buying and selling of grain or grain futures or options involve substantial risk and are not suitable for everyone.

Elaine Kub, CFA is the author of "Mastering the Grain Markets: How Profits Are Really Made" and can be reached at masteringthegrainmarkets@gmail.com or on Twitter @elainekub.

(c) Copyright 2023 DTN, LLC. All rights reserved.

Comments

To comment, please Log In or Join our Community .