Climate-Smart Ag and Carbon Credits

As Climate-Smart Projects Seek to Enroll Farmers, Additionality Question Still Unanswered

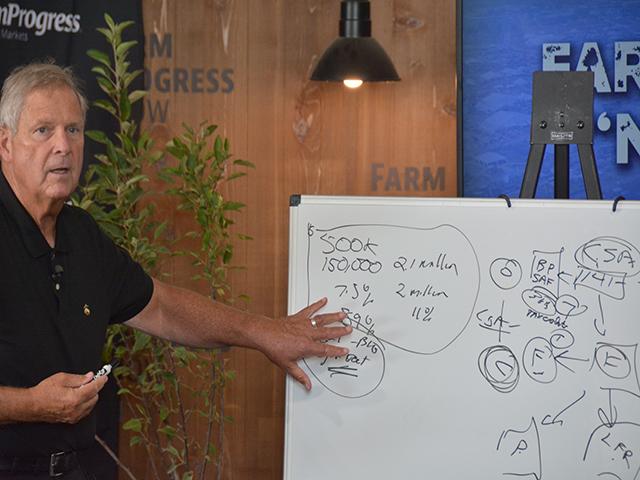

DECATUR, Ill., (DTN) -- As Agriculture Secretary Tom Vilsack spoke at the Farm Progress Show late last month, he highlighted the ways farmers could generate more income from their operations.

Using a whiteboard, the secretary pointed to the 141 climate-smart pilot projects, noting they cut across "every major commodity and every state in the country participating." Vilsack touched on how the practices implemented would give farmers the tools to enroll in an ecosystem service market, such as carbon markets, "where people in industry will pay farmers for the sequestration of carbon and reduction of greenhouse gases." Pointing to sequestering carbon in the soil, Vilsack highlighted the value of forestry and agriculture.

"There are significant resources to increase farm income," Vilsack said.

Yet, USDA rolled out the $3.1 billion Partnership for Climate-Smart Commodities without solving one of the vexing problems that has affected farmers with carbon credit programs: How to deal with the question of "additionality," which means the farmer is taking steps to sequester carbon or reduce emissions that would not happen without the sale of the carbon credits.

That additionality question still hangs out there as projects around the country look to enroll as many as 60,000 farms and more than 25 million acres.

DTN is part of one of the climate-smart projects, "Farmers for Soil Health," which will pay farmers up to $50 an acre for growing cover crops. Farmers for Soil Health involves farmers in at least 19 states who grow corn and soybeans. The National Corn Growers, United Soybean Board, National Pork Board, National Center for Appropriate Technology, National Association of Conservation Districts, Soil Health Institute, University of Missouri, Sustainability Consortium, DTN and The Walton Family Foundation are involved. The project is led by the National Fish & Wildlife Foundation.

QUESTIONS AROUND ADDITIONALITY

The additionality problem was raised to USDA before the department kicked off the 141 climate-smart projects that were announced last fall and contracted to start enrolling farmers now.

Debbie Reed is executive director for the Ecosystem Services Market Consortium, a group of agricultural and food companies, along with conservation groups that advocate for agricultural environmental markets and standards. Reed said she and others tried to get USDA to address some of these problems before they rolled out their 141 pilot projects.

"We talked to them about all of these issues before they did anything," Reed said. "I had companies go up and talk to them about disruptions, and the fact that companies had standards they actually have to follow. So, if they were going to do something, the companies were saying, 'Please do it according to the standards we already have to follow.' Instead, they put themselves out of all of these markets. It's one of the things we have been pointing out."

One problem is the pilot projects were designed by people who understand USDA programs, but don't understand private markets.

"While the money is supposed to create market access for producers, it's going to keep them out of markets because of the additionality issue," Reed said. "It's a big program. I think they (USDA officials) just bit off more than they can chew, frankly, without doing enough of the upfront due diligence. But I also understand some of the temporal concerns they had. The longer they waited, the less likely they were to actually be able to preserve that money and get it out the door. So, they were not listening, which was really too bad."

Chris Harbourt, global head of Carbon for Indigo Ag, said farmers who are about to make practice changes to improve soil health or sequester carbon should consider enrolling in a private voluntary carbon market at the same time.

P[L1] D[0x0] M[300x250] OOP[F] ADUNIT[] T[]

"If you are about to make a practice change, join a carbon program at the same time. Otherwise, you're ineligible for that practice later on in that carbon program," Harbourt said. "It could have some unfortunate impacts of leaving some money on the table down the road."

Indigo is one of the largest carbon-credit generators in the agricultural space with about 5.5 million acres enrolled and paid out $4.6 million. Their average carbon credit payment to farmers in 2022 was $30 per ton.

USDA SEES STANDARDS STILL EVOLVING

Robert Bonnie, USDA's undersecretary for Farm Production and Conservation, in an interview with DTN, said the larger goal of the Partnership for Climate-Smart Commodities is to help producers tap into a variety of potential markets.

"One piece of this, ideally, is you're going to get to a place where there's a lot of opportunities for farmers," Bonnie said. "Maybe they are selling to folks who are interested in a climate-smart soybean, or Sustainable Aviation Fuel, or climate-smart corn. So ideally there will be value out there for farmers who are producing commodities using climate-smart practices. And one of those opportunities might be carbon markets."

Bonnie said there's growing interest in some kind of standardization in the market when it comes to defining additionality. Bonnie pointed to the problems facing producers who have been using soil-health practices for decades, such as no-till and cover crops. These producers often hit a wall with the additionality issues even though they set the standard everyone else is now trying to follow.

"They're not able to increase the amount of carbon appreciably because they have sort of maxed out their soils. They might be cut out," Bonnie said. "Instead, if you have a rule that we're going to provide some backward-looking credit to recognize those types of efforts." He added, "The most important thing for us to do is figure out how we develop incentives that both keep people continuing to do what they are doing, as well as adopt new practices ... ."

As part of the Growing Climate Solutions Act, USDA has to release a report on the "state of carbon markets" that is expected to be completed in October, Bonnie said.

"The challenges with carbon markets right now is there's not a lot of agricultural trading in the carbon markets," Bonnie said. "And one of the challenges is that you have a bunch of different protocols out there -- some good, some bad. And these rules related to additionality vary in a lot of cases; additionality is kind of a subjective measure."

The Growing Climate Solutions Act also gives USDA authority to set up a certification for companies that sell carbon credits. Bonnie said one of the problems right now is that carbon credits have varying standards.

"Some set the bar too low while others demand every single acre being measured, which is too expensive," Bonnie said. "We're right now thinking about how we have this conversation with agriculture in a way that we can design things that actually work and are practical. And producers won't be whipsawed with the changing rules or changing standards."

USDA will work to draft protocols dealing with the metrics and measurements that are both practical and maintain scientific integrity, Bonnie said. That is part of the $300 million effort USDA launched in July to further document the "measurement, monitoring, reporting and verification," (MMRV) of carbon sequestration in agriculture and forestry.

"We have to have a process to look at these protocols so there's going to be a public conversation about this," Bonnie said. "We need agriculture and others to engage in a way that we can figure out how to make that convergence happen where there's more certainty, more economic viability, it deals with early adopters, and it gives a realistic definition of what additionality should look like."

MARKET FOR FARMERS STILL EVOLVING

Iowa farmer Ray Gaesser said the carbon market is still very much in flux for farmers. Gaesser has been a leader in groups such as Solutions From the Land and Iowa Smart Agriculture.

"The whole system isn't right for agriculture and needs to be revamped," Gaesser said. "The carbon credits are set up more for the companies than the farmers. If we're going to use the current system, the whole idea of additionality is not going to work for a lot of people."

Gaesser noted farmers already sequestering carbon in their soil need a more equitable solution. USDA's climate-smart projects are going to play a role in helping document data collection and practices.

"Some of those farmers who are doing practices that are sequestering carbon, maybe there could be some risk in adding these new programs temporarily, but we're all evolving," Gaesser said. "The whole market system is going to have to evolve to a better solution for agriculture, otherwise it's just not going to work at all. There's going to have to be a more equitable way to measure what you are doing."

MARKET PERSPECTIVE

Bruce Knight, a former USDA undersecretary for marketing and regulatory programs, now runs Strategic Conservation Solutions, a consulting firm in Washington, D.C. He played a role in helping some organizations pitch their climate-smart grants and has been studying some of the nuances of the programs. Knight also advises to consider a carbon market with a climate-smart program.

"The most clear thing for a farmer right now is if you are going to take early action and add cover crops, now is the time for you to sell that carbon because of the additionality issues. You won't be able to get paid three or five years from now for soil carbon on the actions you are taking in 2023," Knight said.

Knight said he hopes to see a robust market come out of the climate-smart projects. He thinks farmers may need a third party to help them best take advantage of the programs being marketed.

"If you are going to sign up as a farmer with one of these programs, you should sign up at the same time for whatever existing carbon sales you can do," Knight said. "It's got to be sequential. You can enroll in a carbon-sales program and then stack on the climate-smart projects. But if you start a climate-smart project, then you're not going to be able to enroll in many of these carbon programs under that particular crop practice. You're going to have to add something new."

Knight also recommends farmers take a couple sections of land, enroll in a carbon market then add one of the climate-smart projects. To diversify risk, it would be advantageous to enroll separate tracts of land into different carbon programs, then diversify by being involved in separate climate-smart projects. "I would not go in enrolling 5,000 acres into one market at this point in time," Knight said. "I would treat each of my farm numbers as a different entity for purposes of these programs and then I can make changes on fields in 2024 and 2025. It's like anything else we do in agriculture -- it's diversify, diversify, diversify."

Also see, "Can CFTC Provide Guardrails for Carbon Credits as They Take Off?"

Chris Clayton can be reached at Chris.Clayton@dtn.com

Follow him on X, formerly known as Twitter, @ChrisClaytonDTN

(c) Copyright 2023 DTN, LLC. All rights reserved.