Kub's Den

Where Ag Fits in Commodity 'Supercycle'

Let's start by agreeing that $7 corn isn't necessarily a great thing. It isn't great for livestock feeders, it isn't great for ethanol plants and it isn't great for drivers planning summer road trips. And because $7 corn isn't great for all these customers and customers' customers, it's not that great for corn farmers, either, who may lose some customers. We'll console ourselves by dabbing at tears with fists full of cash, but we'll have to agree that one or two marketing years with corn prices violently spiking up to $7 isn't as nice as it would be if instead we saw a decade of cash corn prices steadily maintaining a profitable level above $4 per bushel.

Once we've agreed on that, we can search around for the forces behind this $7-plus spike -- not in the spirit of celebration, but more in a spirit of blame ... and fear. If we correctly identify the sources of the rally, we can also identify what might happen in the future to turn things around and send them heading in the other direction.

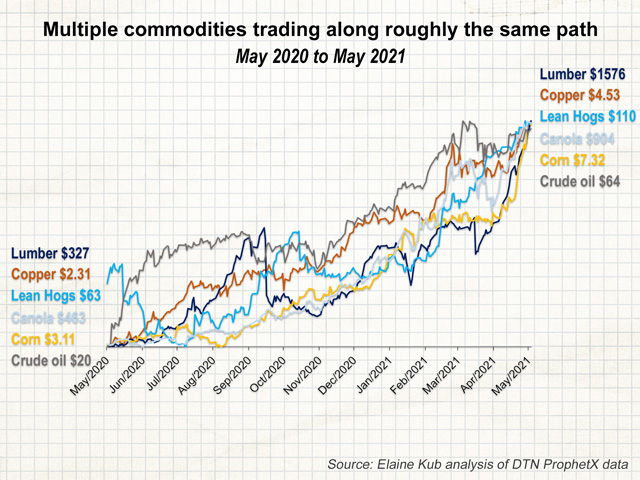

Judging by the way almost every commodity is presently rising to multiyear highs at the same time (not to mention other financial assets, like stocks, also rising to all-time highs at the same time), there is something more going on here than just a little weather scare for Brazil's safrinha corn crop. In May 2021, we've got random length lumber prices at $1,575 per thousand board feet, which is 4.8 times the price seen a year ago of $327. Crude oil prices have more than tripled over the past year, from $20 to $65 per barrel. Corn fits right in here, rising from $3.11 per bushel last May to $7.32 now. Soybeans have risen from $8.47 to $15.60. Canola prices have almost doubled, from C$463 to C$904 per metric ton. Cotton has been on the same rise, from 56 cents to 87 cents per pound. Lean hogs are priced higher than they've been since 2014, currently above $110 per cwt. Cattle prices (dwindling to $115 for live cattle and $131 for feeder cattle) are the frustrating exception to this phenomenon that has grabbed hold of all the other ag commodities and commodities of every other sort, too, including softs (sugar at 17 cents per pound) and, very notably, industrial metals. Copper has been on a nearly straight upwards path since hitting its March 2020 COVID-19 pandemic panic low ($2.06 per pound). At the COMEX futures exchange, the continuous copper chart has even overtaken its previous 2011 high and last Wednesday hit a high of $4.75 per pound. Chinese steel rebar futures hit 5,352 yuan per metric ton at the end of April, equivalent to about $0.37 per pound or $5 for a bundle of #4 rebar. Basically, these days, if you have any kind of useful stuff to sell, somebody wants to buy it and put it to use amid expectations for a rip-roaring economic recovery.

P[L1] D[0x0] M[300x250] OOP[F] ADUNIT[] T[]

I have so far resisted using the term commodities "supercycle," which the financial press started to bandy about at the beginning of this calendar year. It seemed to me like unjustified hype. The last real commodities supercycle -- to my mind -- occurred back in 2008 when China was undertaking great efforts to rapidly build roads, factories and Olympic stadiums, gobbling up steel, rebar, cement, coal and oil. There was a physical, structural background driving the global demand for commodities. In early 2021, traders may have noticed commodity prices all starting to rise and recover at a similar pace, but there wasn't yet a structural economic reason for them to do so.

Now, however, with enough U.S. infrastructure predicted in the future, and with enough fiscal stimulus expected from other developed economies, perhaps there is enough structural demand in the global outlook to justify the word supercycle. Perhaps all the commodities are on simultaneous demand-driven rallies.

Or perhaps this is all just a series of coincidences.

Supercycle or no supercycle, feed grains and oilseeds would be moving higher right now anyway based on a relatively scarce supply scenario after production losses in both North America and South America in 2020 and 2021. Those hot lumber prices, too, might be attributed to scarcity from British Columbian forests after years of mountain pine beetle damage and fires. The prices of any manufactured goods, which aren't commodities but may be rising alongside commodity prices, might be spiking not because of any sudden surge of demand, nor from any long-term shortage, but perhaps from temporary gaps and burps in their supply chains, as transportation logistics still work through the lingering COVID-19 disruptions.

Then there is the idea of a self-fulfilling prophecy. Commodity prices started going up last spring because, hey, they could hardly go down from $20-per-barrel crude oil. Traders started to notice a broad trend of upward movement, which motivated speculators to take long positions, which nudged prices higher, which motivated more buyers, which nudged prices higher, and so forth, until everybody wants in on the action and cash-swamped investors fueled by low interest rates are diving into any financial asset they can find. Total open interest in most of these commodity futures contracts isn't necessarily at an all-time high right now, but one still wonders how much of today's long interest is merely trend-following interest instead of bona fide price-setting.

In any case, looking at these simultaneous commodity rises, and reading every new headline about lumber prices, serves as a reminder that the price gains we've seen for corn, soybeans, wheat, cotton, canola, oats and any other plantable commodity this spring are part of some broader, more mysterious phenomenon.

Elaine Kub is the author of "Mastering the Grain Markets: How Profits Are Really Made" and can be reached at masteringthegrainmarkets@gmail.com or on Twitter @elainekub.

(c) Copyright 2021 DTN, LLC. All rights reserved.