Kub's Den

Hay Bales: High-Priced Time Capsules

If I were a poet, I would write a poem about hay. It would convey how profoundly memories can be affected by scents, and the way dried prairie grass can be a magical form of time travel. Even in the middle of a February blizzard, when the cattle's water tank is frozen and your face is whipped raw by the wind and everything seems miserable, the sunshine and honey aroma of a late-June morning can still hit you from inside a dry hay bale, cracked open and delivered straight to your nostrils and your brain. Time and memory are preserved like a bouquet of dried yellow blossoms inside the previous summer's hay.

In some senses, all dried or preserved food has this quality -- pickles, jerky, beans. They're all little time capsules from the moment when the food was fresh, to the moment in the future when they are consumed, however far in the future that may be. But there is something about the palpable contrast of the outdoor environments in which we create and use hay -- baling hay on a hot summer day versus feeding hay to livestock in a rotten winter storm -- that make it that much more powerful.

Not only powerful, but also expensive these days. On a recent trip to Colorado, I saw small square alfalfa bales priced at $10 per bale in the field (and presumably much higher than that delivered or purchased at retail). Assuming 65 pounds per bale, that puts the alfalfa over $300 per ton. In today's world, where the price of nearly everything -- but especially labor -- has rocketed higher with inflation, this shouldn't be too surprising.

P[L1] D[0x0] M[300x250] OOP[F] ADUNIT[] T[]

It's also born out in official data from USDA's Agricultural Marketing Service across a range of states -- Nebraska and Kansas have alfalfa trades and asking prices ranging from $230 to $300 per ton. Missouri's hay harvest is seen at about 70% complete and, with large pockets of extreme drought across the state, mixed grass rounds of good quality are running $150-$200 per ton, or 60% higher than last June's range of $80-$140 per ton.

All across the nation, hay supply seems to be lighter than hay demand after drought has limited grass yield and condition. There's a widespread area where long-term drought is ongoing, specifically a cloud stretching north and south and east from Omaha. But there are also dominant hay-producing areas farther west that may have received enough rain recently to relieve drought, but which were quite dry earlier in the grass-growing season (i.e., Texas and Oklahoma or Montana and the rest of the Mountain West).

The most recent weekly Crop Progress report shows only 44% of the nation's pasture and range in good or excellent condition, and 24% in poor or very poor condition. Now, that doesn't seem so bad compared to last year's 43% poor or very poor at this time in the season. However, when you consider that a lack of happy grass affects not only the availability of hay that's been cut and baled, but also the underlying yearlong demand for hay when grazing supplies are short, we can see why hay prices have been climbing and why both buyers and sellers are fierce negotiators this summer. In Texas, 43% of pasture and range is still poor or very poor. In Illinois, it's 46%. And in Michigan, a full 68% of pasture and range is classified in those grim categories.

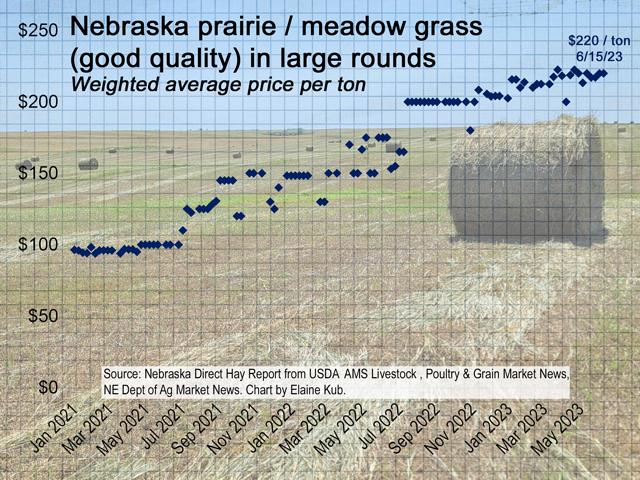

To be sure, the overall condition ratings have been improving compared to last year and especially after recent rains. But hay prices can be sticky once traders get a number in their head, like $200 per ton for prairie hay in large rounds. There's no perfect long-term series of hay prices to show exactly how the market shifts from week to week, because it's not a perfectly standardized commodity with the same interchangeable substance being tested every week. In any given location, there may be varying quality from one trade to the next, or varying delivery terms. However, plain, good-quality prairie/meadow grass baled into large rounds in Nebraska are about as standard and well-tested as the hay market gets, and the psychological benchmark for these bales seems to have risen from $100 per ton in 2021, to $150 per ton at the start of 2022, to $200 per ton once the dry conditions and willingness of the market became clear.

There is no price to put on memory, especially happy memories, and no price to put on perfect June days. But in a world of scarce supply and ever-inflating markets, there is definitely a price to put on hay.

**

Comments above are for educational purposes only and are not meant as specific trade recommendations. The buying and selling of grain or grain futures or options involve substantial risk and are not suitable for everyone.

Elaine Kub, CFA is the author of "Mastering the Grain Markets: How Profits Are Really Made" and can be reached at masteringthegrainmarkets@gmail.com or on Twitter @elainekub

(c) Copyright 2023 DTN, LLC. All rights reserved.