Tracking Russian Attacks on Ukraine Ag

As Attacks on Ukraine Farms Continue, Tour Guide Turns to Advocate, Fundraiser

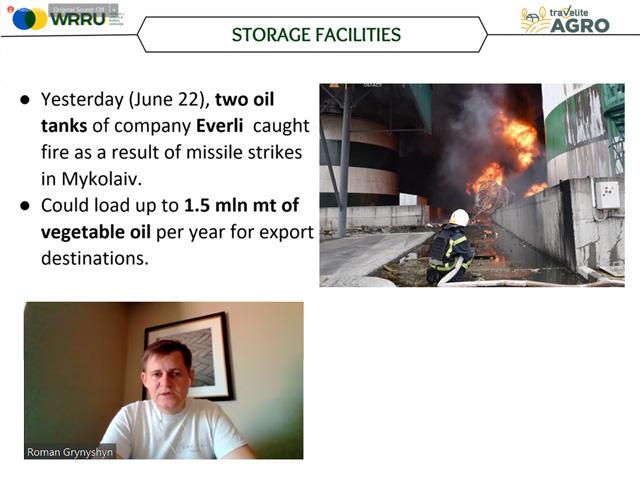

OMAHA (DTN) -- Roman Grynshyn was not surprised this week when he learned Russian missiles had struck grain and sunflower oilseed terminals near Mykolaiv, Ukraine.

The interpreter and owner of a tour-guide business has been keeping tabs on Ukrainian farmers and documenting the impact of Russia's assault on Ukrainian agriculture while visiting rural areas in the U.S., trying to raise money for small farmers who have lost their livelihoods since the war began.

"The news of this came out right after the agreement about Russia, Turkey and some European countries and the possibility they would start allowing some ships to come into ports for the grain," Grynshyn said. "So, this piece of news comes out and they start to burn down the grain and the facilities that store sunflower oil." He added, "So they made this deal less appreciative or less effective for the world."

Mykolaiv is a deep river port comparable to the Port of South Louisiana filled with grain, oilseed and other export-import terminals along the river. Mykolaiv is considered the second-biggest terminal in the country and was stocked with sunflower oil that was ready for export. Both Bunge Ltd and the Canadian company Viterra confirmed their operations were hit during Wednesday's attacks.

Grynshyn spoke to DTN over Zoom from North Dakota where he has been visiting with U.S. farmers and others. Grynshyn has become a point man in the U.S., highlighting the impact of Russia's attacks and making Ukraine's diplomatic stances.

GLOBAL CONDEMNATION

The ramping up of attacks on Ukrainian grain and oilseed export facilities comes as the U.S., European Union, and groups such as the G7 look for ways to get more agricultural products out of Ukraine.

In response Thursday, the U.S. Senate Foreign Relations Committee also voted unanimously on a bipartisan resolution to "condemn the use of starvation and hunger as weapons of war." The resolution criticizes "reckless destruction" and attacks and disruptions of food stocks and farms, as well as attempts to restrict humanitarian aid. Senators said those who use food as a weapon of war should be held accountable for their actions.

"From Ukraine to Syria to Ethiopia, we are watching with horror as bad actors destroy agriculture, deny humanitarian access, and disrupt markets for crucial commodities in a twisted effort to achieve their geopolitical aims through starvation," said Sen. Jeff Merkley, D-Ore., chairman of the committee.

The European Union issued a similar statement Thursday, condemning Russia as "weaponizing food in its war against Ukraine," and declaring Russia as responsible for creating a global food security crisis.

G7 leaders are meeting Friday in Germany to discuss global food security due to the war.

SPOTLIGHTING THE DESTRUCTION

As the war has dragged on, Russian forces have increasingly targeted agricultural facilities because farm commodities make up roughly 40% of Ukraine's exports, Grynshyn said. "They understand that this is something that Ukraine might use in order to stabilize the economy," Grynshyn said. "Therefore, we can see that this is just the beginning."

P[L1] D[0x0] M[300x250] OOP[F] ADUNIT[] T[]

He noted that before the war, Ukrainian agriculture boasted the country was responsible for feeding as many as 600 million people globally. The war has greatly limited that capacity.

At the moment, Ukraine and Russia continue pointing fingers at each other over attacks and mines blocking Ukraine's biggest Black Sea port, Odessa. Earlier this week, Russian missiles struck a food warehouse in Odessa.

The city and port are still controlled by Ukrainian forces, but Russian ships control the Black Sea outside the port. Each country blames the other for mines around the port that block any access for ships to move grain or other foodstuffs out of the country.

Ukraine is unwilling to allow ships into a protected borderline area because doing so would essentially provide access for Russian military ships as well. "That is why our official position is we do not negotiate a deal with Russia until Russian ships withdraw and the corridor is safe," Grynshyn said.

DOCUMENTING LOSSES

Grynshyn's connections to farmers across Ukraine is extensive. Before the war, Grynshyn helped guide Ukrainian farmers for agricultural tours around the world and did the same for farmers in other countries who wanted to see Ukraine's farm economy.

So, when talking about the war, Grynshyn provides an extensive PowerPoint presentation showing the destruction of farms, equipment, livestock, farms and grain elevators across the country.

"Unfortunately, these kinds of images come out every week," he said. "They have been damaging facilities on purpose, and in a lot of cases when they couldn't burn down the elevator in the northern parts of the country, they tore down all of the computer electronics and automation stuff, which is the most expensive equipment."

About 2,300 pieces of farm machinery have been reported as destroyed, but Grynshyn said the situation is much harder to gauge in the occupied parts of the country right now. The government estimates 30% of farm fields are either now occupied or considered unsafe because of bombing and land mines. It is simply dangerous for some farmers to try to get into their fields.

"It is like Russian roulette for them to harvest or not," he said.

TRYING TO MOVE GRAIN

Rattling off numbers of commodities that are unable to get out of the country, Grynshyn said the Ukraine government's last estimates amounted to 7 million metric tons (mmt) of wheat, 14 mmt of corn and 3 mmt of sunflower oil. "Those numbers obviously change with the bombings," he added.

He noted the country has exported 1.3 mmt so far in June, up nearly 50% from May, but still small compared to normal volumes. Grynshyn also pointed to more grain coming out of Romania's port of Constanta, but that volume is still small. Russia has bombed a rail line that moved from Ukraine to Constanta as well, which has further exacerbated the situation.

Last week, President Joe Biden said the U.S. government would help build grain silos in Poland to help with Ukrainian exports. Biden highlighted the issues with Ukraine's rail gauges being different from other rail tracks in Europe.

"So, we're going to build silos -- temporary silos -- in the borders of Ukraine, including in Poland, so we can transfer it from those cars into those silos, into cars in Europe, and get it out to the ocean, and get it across the world. But it's taking time," Biden said.

Grynshyn said he understood there were still logistical issues to building silos on either the Poland or Ukraine side. For now, different foundations have been providing more immediate help with silo bags to be used for short-term harvest storage.

SOLICITING AID TO FARMERS

Grynshyn was an English teacher in Ukraine who became a translator and did some work with the U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID). He then got into the business of providing agricultural tours for Ukrainian farmers and for others wanting to see Ukrainian agriculture. Grynshyn broadened his business to provide tours globally. When the war began in February, he dropped his commercial projects and began raising money and speaking about Ukraine's agriculture and the impacts of the war.

Grynshyn now does biweekly YouTube updates. His organization, World to Rebuild Rural Ukraine (WRRU), is raising funds to help some small farmers in Ukraine rebuild after losing their farms, equipment and livestock. Grynshyn noted smaller farmers in Ukraine operate just over one-quarter of the land but produce as much as 45% of the country's livestock and 30% of crops.

"They don't have access to government programs and aren't eligible for loans to reconstruct," Grynshyn said. "They don't have possessions to sell, and some of them don't have a place to live."

His organization, which has a board of consultants and experts on Ukraine, is soliciting donations from farmers globally. Among those board members is Charles Stoltenow, dean and director of the University of Nebraska Extension, as well as Neal Kinsey, who owns a soil consulting service in Missouri. WRRU has testimonials from its four board members on its website seeking donations.

Grynshyn is asking farmers to pledge 1 cent per bushel of crops or 1 pound of animal production.

"We are trying hard to spread the word that is most understandable to farmers," Grynshyn said. "We have a global food crisis that is partially due to the war in Ukraine. So right now, we are asking the farmers worldwide to pledge at this moment pennies from their harvest so they can help the small farmers in Ukraine."

Grynshyn estimates his efforts so far have raised between $15,000 to $20,000, but donations keep coming from other countries. He noted the work only started a few months ago, and the project is just getting off the ground. Aid also likely will be needed for years to come.

More details on WRRU can be found at the group's website, www.wrru.org.

Chris Clayton can be reached at Chris.Clayton@dtn.com

Follow him on Twitter @ChrisClaytonDTN

(c) Copyright 2022 DTN, LLC. All rights reserved.