Ag Weather Forum

What Does a Sudden Stratospheric Warming Event Mean?

If you listen to those who discuss long-range weather patterns, you might have heard some of them use the term "sudden stratospheric warming event" (SSW event) to describe potential for bringing cold, arctic air down through the mid-latitudes. For a lot of folks, this is the first time hearing this term and it can be confusing. So what does it really mean?

First, we have to understand how our atmosphere works. During the cold half of the year, the North Pole develops a somewhat continuous low-pressure center near and over the Pole. This is called the polar vortex and gets a lot of attention during the winter. Most forecasters use it to describe where the really cold, arctic air comes from, and the mechanism by which it moves farther south. The same happens over the South Pole, too, but this vortex is much stronger than the one in the north.

The polar vortex does not only exist in the troposphere, but it also extends up into the stratosphere. The troposphere is where weather happens -- where clouds occur, where the jet stream exists, and where weather systems move. The layer above the troposphere is the stratosphere and is generally a very stable layer of air, with little effect on the troposphere other than to put a sort of "cap" on how high clouds and the jet stream can go. The vortex brings westerly winds around the North Pole and builds very cold air during the winter. When it is strong, the polar vortex keeps the cold locked up near the Pole. If it gets disturbed, the vortex can move off the Pole or break into pieces and send little vortices farther south around the globe.

You can think of the polar vortex a lot like a drain in a sink. If you fill the sink with water and unplug the drain, a natural vortex develops and sends water from the top to the drain. You can disturb it by putting your hand in the water and through the vortex. You might see it break into pieces or get pushed away from the drain, resulting in the sink water not draining properly. That is usually how we see the polar vortex being disturbed in the winter. Blocking ridges of high pressure in the troposphere impinge upon the vortex and move it around the Northern Hemisphere, sometimes splitting it into pieces or just shoving it off the Pole into Siberia, Canada, or northern Europe.

P[L1] D[0x0] M[300x250] OOP[F] ADUNIT[] T[]

However, you can also put the plug back into the drain from above and see the same sort of thing happen. Eventually, the vortex shuts down, so it is not a perfect analogy until the end of winter. But putting the plug in from above can cause the same sort of disruptions to the surface polar vortex, shoving it off the North Pole into the mid-latitudes, or splitting it into pieces.

The vortex in the stratosphere is maintained by waves traveling around the Pole. If the waves break, like waves on the beach, then the vortex breaks down from above, eventually working its way to the surface, like the plug in the drain. A way we can detect this occurring in advance is by looking at the temperature forecast within the stratosphere. If temperatures rise very quickly, then the waves break and the vortex begins its demise. That is the SSW signature we are looking for.

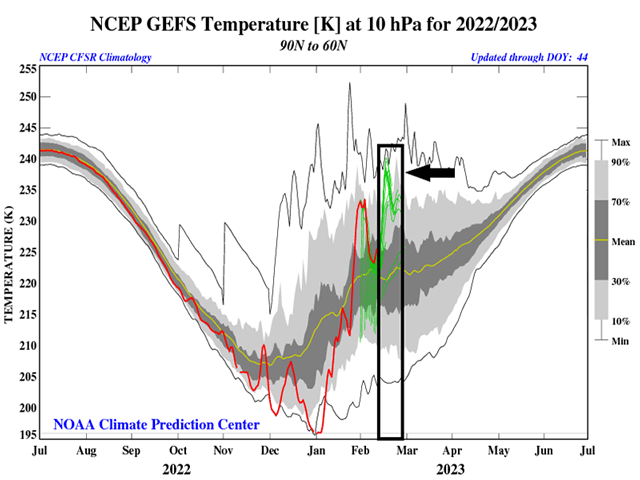

Lots of models are predicting an SSW event at the end of February. The attached image shows a sharp spike upward over the next week or two at a height of 10 millibars, or roughly 17 to 20 miles above the surface, well above where planes fly. However, the breakdown process is not immediate. Like a lot of weather phenomena, the process is slow, taking at least a couple of weeks to reach the surface, sometimes up to four weeks. That would mean we should expect to see models produce a displacement or disruption in the polar vortex around the middle or end of March, a little too far in the future to trust models at putting cold air in the right place and right time. Other ridges of high pressure within the troposphere will affect where any splits or displacements may occur, and models may or may not be handling these properly a month in advance. The SSW event may not get cooperation from these effects either, keeping the cold air locked closer to the Pole anyway.

But an SSW event provides a signal for forecasters to use when looking at the long-range forecasts. Seeing the polar vortex breaking up would make sense in this time frame and would key them into believing a disruption to the polar vortex may occur. It may not give us an exact place and time just yet, but the clues are out there if we are looking for it.

If you hear the term from now on, just think back to the drain analogy and the disruption in the polar vortex -- a sign that cold, arctic temperatures may again be on their way south. Any intrusions of cold air before the middle of March would be due to other means.

**

This week, I am in Louisville, Kentucky, for the National Farm Machinery Show. There, my colleague DTN Lead Analyst Todd Hultman and I will present our latest market and weather outlooks for the 2023 season. If you're in town, I hope you'll visit our presentation each day of the event and stop by the DTN booth and say hi.

To find updated radar and analysis from DTN, head over to https://www.dtnpf.com/…

John Baranick can be reached at john.baranick@dtn.com

(c) Copyright 2023 DTN, LLC. All rights reserved.