Kub's Den

Calmer Supply Chains May Stabilize Inflationary Influences on Commodity Prices

Commodity producers don't necessarily want to see commodity prices go down, but when we think about a big factor that's been causing higher commodity prices -- inflation due to shipping costs and supply chain inefficiencies and middlemen -- then there may be every reason to rejoice when some of those inefficiencies start to wane.

In recent years, the actual farm production of food commodities has accounted for less than $0.08 of each $1.00 of U.S. consumers' expenditure on domestically produced food, according to USDA's Food Dollar Series, with more like $0.15 going to food processing, $0.04 to transportation, $0.03 to packaging, or $0.23 going to wholesalers and retailers in the supply chain. Those are the portions of a grocery store receipt that may be able to come back down if inflation can slow or stop, but that may only happen if the global supply chain can finally heal its shortcomings and if freight prices can finally come back down too.

Typically, the relationship between agricultural commodity prices and freight prices is best examined through the Baltic Dry Index -- a measure of what it costs to hire a huge ocean-going vessel to haul dry bulk goods (like soybeans, or coal) from one continent to another. On occasion, the Baltic Dry Index can even be read as a kind of proxy for overall global economic activity or shipping industry pain. But even during the height of the pandemic and lockdowns, and the peak of the global manufacturing and shipping disruptions, the Baltic Dry Index never gave a full picture of what was going on because dry bulk goods are only one category of thing that the economy needs. You've no doubt noticed that we also need things that get shipped on trains, trucks and airplanes, things that need to be manufactured at plants staffed by people who are vulnerable to viruses and that rely on other parts that need to be manufactured in other plants in whole other countries with their own supply chain woes. We could count the number of container ships backed up at the port of Los Angeles, for instance, as a proxy for that sort of supply chain upheaval, but there wasn't any great, widely accepted overall measure of the global supply chain's status.

P[L1] D[0x0] M[300x250] OOP[F] ADUNIT[] T[]

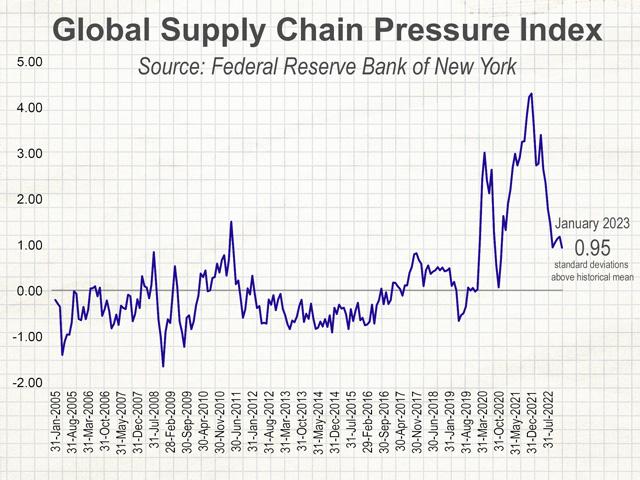

For the past year, however, the Federal Reserve Bank of New York has been presenting its "Global Supply Chain Pressure Index" -- the GSCPI -- calculated from a variety of data that looks back as far as 1997, including shipping costs (such as the Baltic Dry Index), airfreight costs, delivery times and manufacturing backlogs across seven interconnected economies: China, the euro area, Japan, South Korea, Taiwan, the United Kingdom and the United States. Each individual index is scaled by its own standard deviation, then smooshed together into one, overarching, amalgamated measure of how far off the global supply chain is from its baseline -- either above (providers stretched tight and charging high freight prices) or below (peachy keen).

As you can imagine, the state of the global supply chain, as measured by this GSCPI, was off-the-charts frantic in April 2020, then spiked to an all-time high of 4.31 standard deviations above its mean in December 2021. It has been improving ever since. In the latest figure released this week, the GSCPI for January 2023 showed the global supply chain's status is now less than 1 standard deviation away from its "normal" state.

This is great news for anyone who needs to buy anything -- from a car to a plastic tchotchke to a specific tractor part that's needed before spring planting season. It's good news, too, for all the grocery shoppers who may expect the inflated prices of packaging, shipping and retailing to someday come back down so that more of the dollars they spend on food in America actually goes toward the food itself.

It's less clear if there will be any direct effect on commodity futures prices as these supply chain measures retreat back into normalcy. On the one hand, as inflation eases, there may be less eagerness from investors to buy and hold commodities as an "inflation hedge" in their financial portfolios. On the other hand, diminishing freight costs can help keep down the landed costs of exported grain, can help prevent sticker shock for foreign end users and may therefore ultimately forestall demand destruction for the commodities themselves.

**

Comments above are for educational purposes only and are not meant as specific trade recommendations. The buying and selling of grain or grain futures or options involve substantial risk and are not suitable for everyone.

Elaine Kub, CFA is the author of "Mastering the Grain Markets: How Profits Are Really Made" and can be reached at masteringthegrainmarkets@gmail.com or on Twitter @elainekub.

(c) Copyright 2023 DTN, LLC. All rights reserved.