Kub's Den

Why South America Drives Winter Oilseed Markets

Brazil and Argentina are considering the creation of a shared currency, to be called "the sur," kind of like the euro, as reported by the Financial Times and other media outlets at the start of this week. A shared currency would theoretically facilitate easier trade between countries within the region, but this "sur" currency isn't something to get worked up about ... yet. For one thing, it's just a suggestion at this point, with really questionable political motivations for either country, and remember that it took the euro 35 years to go from idea to reality.

One detail in the reporting stuck out to me -- the euro itself is an influential currency because its activity encompasses about 14% of global GDP. Meanwhile, "a currency union that covered all of Latin America would represent about 5% of global GDP," according to Financial Times estimates.

This got me thinking -- how much of the soybean market is represented by "Latin America," or South America, specifically? How much of the global edible oils market?

At this time of year, it definitely seems like Brazilian and Argentinean weather forecasts are the driver of day-to-day soybean futures price changes. And from the data, we can see why: The 153 million metric tons (mmt) of soybeans now predicted to be harvested in Brazil this winter, together with the 45 mmt of soybeans predicted for the Argentinean harvest and 10 mmt of soybeans from Paraguay, altogether account for a majority of all the globe's annual soybean production -- 54%, to be precise, coming from South America. Those are the latest official projections from the USDA's January World Agricultural Supply and Demand Estimates (WASDE), but they are, of course, subject to change as weather conditions change over the next couple of months, and private estimators may believe the record-large Brazilian crop will get even larger or the drought-diminished Argentinean crop may get even smaller. In any case, when it comes to telling the story of global soybean supplies -- South America has the microphone.

P[L1] D[0x0] M[300x250] OOP[F] ADUNIT[] T[]

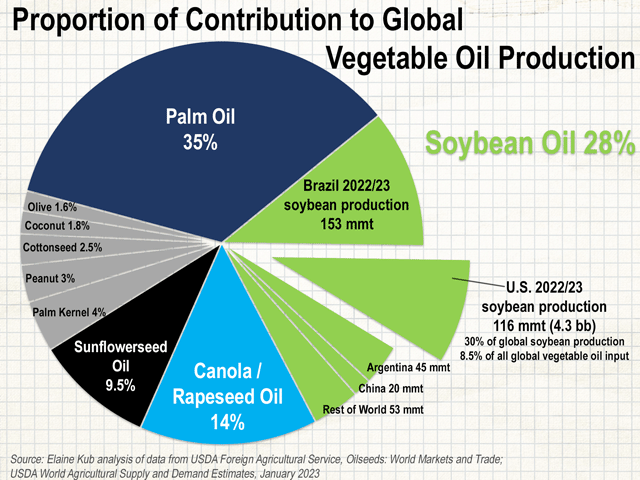

However, even the dominant soybean production of South America doesn't really hold sway over the broader global vegetable oil (edible oils) market. The soybean oil that will come from South America's 208 mmt of soybeans will only add up to 15% of the entire global vegetable oil market, where soybean oil itself plays second fiddle (only 28% market share) to the dominant palm oil market (35% market share).

The United States, with 30% of global soybean production, contributes a proportion of soybean oil equivalent to 8.5% of all global vegetable oil. The U.S. also produces canola oil, sunflower seed oil, peanut oil and cottonseed oil, but these are slivers of the pie compared to the major market movers.

The interesting phenomenon is how closely palm oil prices and soybean oil prices move together in tandem -- and even take the prices for cash soybeans, canola, sunflowers and other oilseeds along for the ride. From that observation, anyone who wants to develop an outlook for future oilseed prices might be better served by analyzing Indonesian palm oil supply and demand than by tallying European soybean numbers or even Ukrainian sunflower production.

Palm oil gets used in so many industrial applications -- not just in bakery products, chocolate and other "edible oil" applications, but also in soap, deodorant, cosmetics, shampoo, candles, biofuels, lubricants and various chemicals used in manufacturing other commodities or pharmaceuticals. This makes palm oil, to some degree, a substitute for crude oil, or at least for certain specific petroleum-based products. A very quick back-of-the-envelope calculation shows that the weekly returns of Brent crude oil futures and Malaysian palm oil futures have had a positive correlation of 0.18 during the past 10 years -- a pretty impressive relationship for two otherwise dissimilar markets.

With this in mind, if you believe that crude oil prices are headed higher in 2023 (and I personally am leaning in this direction), then you may also start to feel a little bullish about a recovery in palm oil futures. And if you start to feel a little bullish about palm oil futures, you might also start to feel a little bullish for soybean oil prices (even at 62 cents). None of this even requires any South American weather or long-range North American planting intentions math to make the argument.

There are, of course, many various other chaotic variables that will drive the direction of the global oilseed markets over the coming weeks and months, but when it comes to judging the importance of each crop's influence to global edible oils prices, it helps to keep a sense of proportion in mind.

**

Comments above are for educational purposes only and are not meant as specific trade recommendations. The buying and selling of grain or grain futures or options involve substantial risk and are not suitable for everyone.

Elaine Kub, CFA is the author of "Mastering the Grain Markets: How Profits Are Really Made" and can be reached at masteringthegrainmarkets@gmail.com or on Twitter @elainekub.

(c) Copyright 2023 DTN, LLC. All rights reserved.