Todd's Take

Is the Wheat Market Ready for Another Chernobyl?

I never pictured myself as the old guy saying, "I remember back when Chernobyl happened," but that is where I find myself these days. In April 1986, I was 26 years old and in my second year on the trading desk at Delta Futures Group in Omaha, following quotes on a big, monochrome DTN screen with green numbers.

Back then, we phoned in orders to Henry Shatkin's trading desk on the floor of the Chicago Board of Trade. As was common then, prices would make big moves first and we would only hear the explanations much later, sometimes the next day. Apparently, the accident at Chernobyl took place over the weekend, but as I recall, traders weren't initially sure how serious to take the news.

July Chicago wheat, which closed Friday, April 25, 1986, at $2.53 3/4, was up 7 cents Monday after the news broke over the weekend. Prices were up 12 3/4 cents Tuesday and finished up 20 cents Wednesday, settling at $2.93 1/2. Back when wheat prices were much cheaper, the nearly 40-cent gain in three emotional days was a big surprise, difficult to adequately describe today.

It's also important to remember this was a time when the world was drowning under big piles of grain. Just a couple weeks before the Chernobyl accident, USDA estimated U.S. ending wheat stocks at 1.89 billion bushels (bb), almost an entire year's worth of demand. U.S. corn ending stocks were estimated at 3.57 bb, an extremely large pile at a time when annual demand was less than half of what it is today.

These memories of Chernobyl were triggered Thursday after NBCNews.com reported Russia allegedly told workers at the nuclear plant in Zaporizhzhia not to go to work Friday (see https://www.nbcnews.com/…). NBC News said it heard about the news from Ukraine's military intelligence. It is difficult to know if the report is true and, if it is, it is difficult to know exactly what is happening.

Is the plant leaking radiation? Is the plant at risk of a meltdown? Is Russia getting ready to intentionally sabotage the plant? We don't know, but those dangerous possibilities, if any came to pass, would spell long-term trouble for people in surrounding areas and for Ukraine's food production for a long time to come.

P[L1] D[0x0] M[300x250] OOP[F] ADUNIT[] T[]

Russian forces took over the plant in March and have forced Ukrainian workers to stay at the plant since. Russia's head of radioactive defense forces, Igor Kirillov, said in a briefing reported by NBC News, the plant's backup systems had been damaged by shelling. He also explained in the event of an accident, radioactive material could spread to Germany, Poland and Slovakia.

Olena Pareniuk with the Institute for Safety Problems of Nuclear Power Plants of National Academy of Sciences of Ukraine described an even more dire possibility to NPR's Juana Summers (see https://www.npr.org/…).

Pareniuk explained there is only one power line currently supporting the plant at Zaporizhzhia. If the line were to be lost, diesel generators could keep the core cool as long as fuel were available, but without power, the core will melt down and release radionuclides into the environment, as happened in Fukushima in 2011.

If anything like the scenarios described above were to happen, it is fair to say we would see wheat prices jump a lot more than 40 cents higher. If you think marketing GMO wheat is a tough sell, just imagine how impossible it would be to convince others to take radioactive wheat and other grain from Ukraine off your hands for the next decade or more.

In 2016, Reuters reported on a study by Greenpeace that purported to show dangerous levels of radiation in grain and other foods near Chernobyl 30 years after the accident (see https://www.reuters.com/…).

For the sake of humanity, I hope this is a false alarm. For those who try to manage risk on the farm, it is another powerful reminder of why you should never be tempted by some hotshot telling you he has a mathematical formula for defining risk.

True risk is not based on past prices, measures of volatility or any secret recipes for pricing options. True risk comes from the unexpected twists and turns of future events -- surprises that happen more often than statistical probabilities say they should.

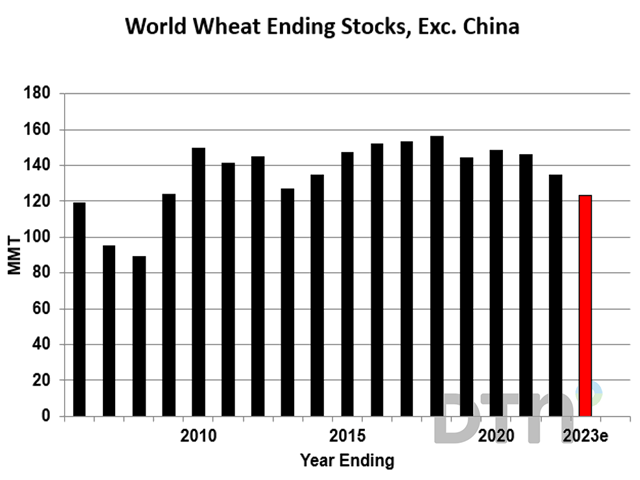

Today's global wheat supplies are much tighter than they were in 1986. If USDA is correct, the world's wheat supplies outside of China in 2022-23 will be at their lowest in 15 years. I don't know if we will remember the name Zaporizhzhia 30 years from now, but the bullish risk in wheat is currently much bigger than many realize. If the threat at Zaporizhzhia is not a false alarm, speculators currently short in the wheat market will once again find they've written checks they can't cash.

**

Comments above are for educational purposes only and are not meant as specific trade recommendations. The buying and selling of grain or grain futures or options involve substantial risk and are not suitable for everyone.

Todd Hultman can be found at Todd.Hultman@dtn.com.

Follow him on Twitter @ToddHultman1

(c) Copyright 2022 DTN, LLC. All rights reserved.