Kub's Den

Bad News on Both Ends of Basis Spectrum

Grain basis bids are either too strong or too weak, depending on who you're talking to, and nobody's happy about it. The underlying source of the consternation is the same thing that's causing so much strife in every other aspect of economic life right now: high energy prices.

Basis here means the difference between the local price for physical grain and the benchmark futures price for that grain. It can be either negative or positive. For instance, a negative basis of -30Z (30 cents under the December "Z" contract futures) may be a normal value for corn at a countryside elevator in Iowa, meaning if benchmark Chicago futures are trading at $6.50, we might expect to see a $6.20 cash price for corn delivered to the elevator. Meanwhile, a positive basis of +15 (15 cents over the futures) may be a normal value for corn at a feedlot in the panhandle of Texas, and if 2022 was a "normal" year, we might expect to see the cash price for spot corn in that region today at about $7.95 per bushel.

Spoiler alert. It's not.

If grain basis bids were weak everywhere -- let's say 60 under in Iowa and 20 under in Texas -- then at least the end users who need to buy feed for their animals would be happy about getting a cheap price tag on their flat-priced grain. If grain basis bids were strong everywhere -- let's say only 10 under in eastern North Dakota -- then at least farmers would be happier about the revenue they receive. They might worry about high prices rationing demand and damaging the profitability of their customers and customers' customers, but at least there would be a silver lining.

P[L1] D[0x0] M[300x250] OOP[F] ADUNIT[] T[]

Now, however, when the basis spectrum widens out on both ends, no one wins. Because of higher transportation costs (because of higher fuel costs), the low prices get lower and the high prices get higher. Flat prices at the farm gate are pressured downward because it costs so much to ship the grain to a storage facility, and at the very same time, flat prices for the end users are inflated upward because they, too, must pay for shipping. This phenomenon is particularly acute at the far edges of the Corn Belt (or the farthest-flung corners of the globe), where shipping distances tend to be the longest.

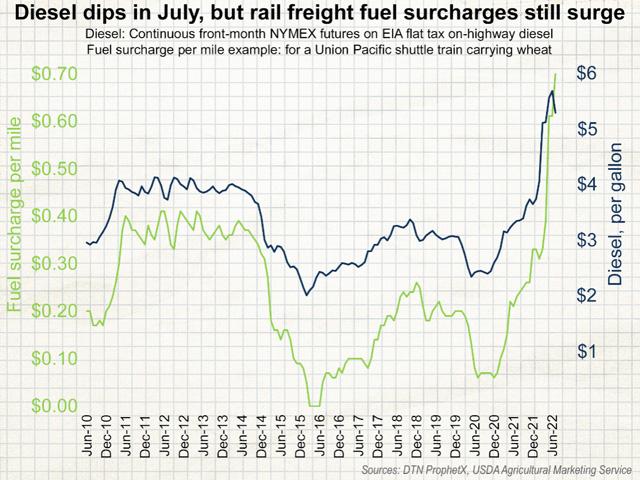

Consider all the wheat that's been recently harvested in western Kansas, which may be shipped west for export rather than east for domestic use. The railroad's wheat freight rates for a shuttle train's 1,600-mile trip from Colby, Kansas, to Portland, Oregon, for instance, are equivalent to $1.90 per bushel, according to USDA's July 7, 2022, Grain Transportation Report, making a bushel of wheat, which is worth $8.85 in Kansas, turn into a bushel with a $10.75 price tag at a Pacific Northwest port facility. Within the total $1.90-per-bushel freight cost, $0.30 of that comes from the railroad's fuel surcharge alone. Last July, the fuel surcharge portion of that rail movement was only $0.09 per bushel. At its previous high in mid-2013, the fuel surcharge still only accounted for $0.16 per bushel of the total freight cost. So, we are very much in unusual territory these days, with fuel costs drastically driving up the overall price of transportation.

This is true for anything being shipped anywhere by any means. Diesel prices are directly driving up trucking costs, of course, and barge freight rates are also running about 50% higher than they were a year ago. The fuel surcharge portion of rail freight rates for shipping soybeans on a shuttle train from Council Bluffs, Iowa, to New Orleans, Louisiana, is now $0.22 per bushel (out of a total $1.54 per bushel freight rate) instead of last July's $0.07 per bushel. And if you're shipping corn from Des Moines, Iowa, to Amarillo, Texas, it would cost you $1.25 per bushel to send a shuttle train there, with $0.14 of that rate coming from the fuel surcharge alone.

When freight rates jump by 10 or 20 cents per bushel due to higher energy costs, those dimes must come from somewhere. Either the shipper can pay the farmer 10 cents less or charge the end user 10 cents more ... or both, and that seems to be what's happening.

Over the past decade, the average spread between the highest cash bids for corn in the country (usually around the panhandle of Texas) and the lowest cash bids for corn in the country (usually northwestern North Dakota or the thumb of Michigan) has been almost exactly $1.00 per bushel, e.g. $5.30 at a Texas feedlot while $4.30 at a North Dakota elevator in December 2020. Today, the spread between these zones is $2.15 wide: e.g. $8.35 in Texas and $6.20 in North Dakota. The wider spread is partly a function of the increased transportation costs, but also a function of the scarcity of local old-crop supply in the droughty West. (I'm using Friday's flat price bids instead of basis values, because basis bids get funky at this time of year when they're based off the September futures contract, and its day-to-day movements aren't representative of old crop supply and demand. And yet, we still have to buy and sell grain, and feed livestock, and operate ethanol plants for the next few months.)

We can see a clearer picture of how transportation costs alone influence basis when we survey new crop bids across the country, which don't have as much supply panic included to muddy the water. That typical dollar-wide spread between North Dakota and Texas is looking $1.50 wide in new crop basis bids: -90Z for new crop corn at a North Dakota elevator and +60Z for new crop corn in the panhandle of Texas. Cheaper than usual for the farmers; even more painfully expensive than usual for the end users.

Much depends on how things shake out in the next few months before row crop harvest. Diesel prices have been dipping lower since their mid-June peak, but we have yet to see that monthly adjustment in rail freight fuel surcharges, even while rail service levels for grain trains have been persistently bad through the first half of this year. The number of unfilled grain car orders have been hitting record levels, peaking above 15,000 cars in late June, and although there has been a recent improvement during this relatively quiet portion of the year, it's hard not to worry about how backlogged the supply chain might get once row crop harvest season begins. Grain shippers could end up paying through the nose to receive bad service or to find desperate replacements on the secondary freight market. That won't help the basis scenario for anyone -- farmers or end users. If transportation costs don't abate, countryside basis bids can't improve.

**

Comments above are for educational purposes only and are not meant as specific trade recommendations. The buying and selling of grain or grain futures or options involve substantial risk and are not suitable for everyone.

Elaine Kub, CFA is the author of "Mastering the Grain Markets: How Profits Are Really Made" and can be reached at masteringthegrainmarkets@gmail.com or on Twitter @elainekub.

(c) Copyright 2022 DTN, LLC. All rights reserved.