Kub's Den

Specialty Crops in Battle for Acres as Russia-Ukraine War Persists

It feels grotesque to talk about the usual spring "battle for acres" between corn, soybeans and wheat in the Northern Hemisphere, when there are real battles, deaths, injuries and destruction happening in war-torn Ukraine. Nevertheless, the two concepts are related. While commodity shipments across the Black Sea are disrupted, prices have spiked. International consumers may find it's not only wheat products that become unaffordable, but cooking oil as well. Ukraine is the world's largest sunflower grower and by far the largest exporter of sunflower oil.

Eventually, a summer and fall 2022 harvest of wheat and oilseeds may backfill the supply chain to make up for what is presently inaccessible from the Black Sea region. But, in the meantime, the high prices for all these crops will influence farmers' planting decisions worldwide.

Specifically, spot bids for oil variety sunflowers in North Dakota in late March 2022 are posted anywhere from $30 per cwt ($0.30 per pound) at local elevators to $38 per cwt at the crush plants. Meanwhile, new-crop bids might be $28 to $32, all of which competes with record highs from 2008 and 2011. North Dakota State University Extension's projected 2022 crop budgets suggest it might cost only about $0.18 per pound to grow the crop (subject to individual assumptions about fertilizer costs, land charges and other inputs), and you might get 1,740 pounds per acre. Any way you look at it, sunflowers are expected to be attractively profitable crops in 2022 for those in the right geography to grow them.

P[L1] D[0x0] M[300x250] OOP[F] ADUNIT[] T[]

They're also just an attractive crop, period. Think of the dazzling Italian vistas in the 2003 movie "Under the Tuscan Sun," or the eye-catching blue-sky/yellow-field motif in Ukraine's flag, or the endless South Dakota sky over rolling fields of east-facing big, yellow flowers. There's nothing like it.

More than once, I've stood in the cooking oil aisle of a South Dakota grocery store, looked at the label on a bottle of sunflower oil, seen the words "from Ukraine," and wondered, "What the heck?" When there are all these lovely fields of sunflowers surrounding us, why is Walmart shipping in sunflower oil from half a world away? But this is just a symptom of my own backyarditis. The vast majority of the United States is not surrounded by sunflower fields, and we really don't have enough of the oil to meet demand.

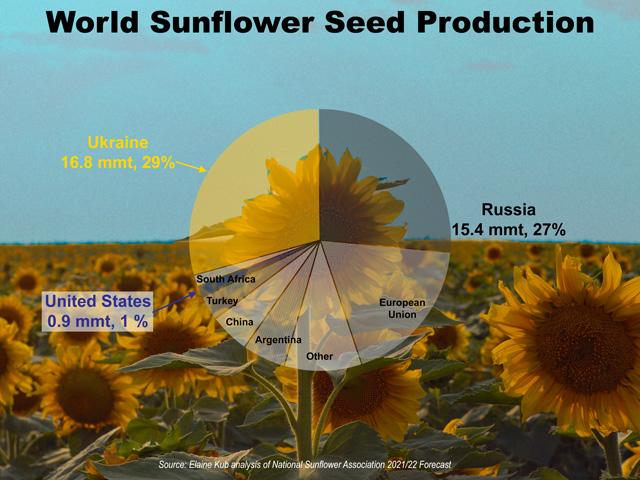

Sunflower production in the United States is small by any measure -- taking place in only a few dozen counties, mostly in North Dakota (where there are processing plants to buy the product), central South Dakota, Kansas and Texas. In global terms, the U.S. is only the seventh-largest producer of sunflowers (with 1.7 billion pounds of oil sunflowers produced in 2021, or 1% of the world total), just below Turkey and just above South Africa.

Meanwhile, Ukraine grows 29% of global sunflower production and Russia grows 27%. More alarmingly, Ukraine has been far and away the leader, providing the rest of the world with refined sunflower cooking oil, representing 54% of sunflower oil available to the global export market in 2020 and 49% in 2021. Russia is the second-largest provider of sunflower oil, but with only 27% market share.

We might think: If Putin's war against Ukraine has made sunflower oil temporarily scarce and high-priced, then consumers should just switch to another cooking oil -- canola oil, peanut oil, safflower oil, cottonseed oil, soybean oil or palm oil -- right? It's not that simple. Recall that the Southern Hemisphere's crop yields have been damaged by drought in early 2022. Argentina's sunflower crop is now estimated at only 3.3 million metric tons (mmt) compared to last year's 3.5 mmt). And Malaysian palm oil futures and soybean oil futures were sailing toward never-before-seen, all-time highs in 2021 and again in February 2022, even before the Russian invasion began. These edible oil markets have noted a rationing of demand in recent weeks at both the consumer and nationwide import levels, as buyers have balked at high prices and bought only their bare minimum hand-to-mouth needs. The tight supply scenario for all edible oils across the globe emphasizes that there are no cheap substitutes easily available to make up for Ukraine's trapped sunflower oil and market prices are expected to remain elevated for the foreseeable future.

Located at basically the same latitude as the Dakotas, Ukrainian farmers will -- to the degree they are able to do so safely amid the conflict -- sow crops at basically the same spring schedule that we have here. Sunflowers tolerate relatively later planting than corn, for instance, even potentially into early June. Therefore, it's not too late for the scenario to get sorted out in Ukraine in a way that would allow their 2022 sunflower crop and sunflower oil supply to become available as hoped for, as long as the shipping infrastructure isn't hopelessly damaged.

It's also not too early for U.S. farmers to be considering these short- and medium-term opportunities in the markets for specialty crops and oilseeds: sunflowers, safflowers, peanuts, cottonseed, flaxseed, canola and -- don't forget -- soybeans.

Elaine Kub, CFA, is the author of "Mastering the Grain Markets: How Profits Are Really Made" and can be reached at masteringthegrainmarkets@gmail.com or on Twitter @elainekub.

(c) Copyright 2022 DTN, LLC. All rights reserved.