Kub's Den

Corn 'Contango' Inverts to Signal Bullishness

Contango. Where did this funny word come from? Were old-time futures traders holding each other in their arms and dancing to sultry Argentine music? Maybe not.

History tells us the etymology comes from the "continuation" fees that traders in 1800s London would pay each other to defer settlement on forward contracts. And ever since then, economists have been trying to figure out just why commodity futures prices vary across the calendar, higher in some timeframes than others.

In the 1930s, John Maynard Keynes wrestled with the problem and theorized that because farmers were relatively more desperate than end users to lock in future prices for grain, they would accept lower prices in the future than what was available on the spot market, leading to a normal state of "backwardation" with deferred prices lower than nearby prices.

That theory obviously hasn't held up well.

So, others, including Fama and French*, have added theories that consider the costs of storing commodities over time -- "carrying" costs. When deferred commodity prices are higher than nearby prices, the market is said to be in "contango," or to use the grain industry's chosen nomenclature, the market is in its normal "carry" structure.

Ultimately, whether commodity contango or backwardation is the norm depends on what kind of commodity we're talking about.

Crude oil, which is constantly pumped to the market every day of the year, has a futures structure that frequently wavers between contango and backwardation depending on supply and demand.

P[L1] D[0x0] M[300x250] OOP[F] ADUNIT[] T[]

Grains, which are produced annually and must be stored through most of a year, typically price their futures contracts in a carry structure. Metals, like copper, which must also be stored in warehouses, also typically have futures prices in contango.

This has become a hot topic again because almost every commodity market has either slipped into unusual backwardation or, for the ones that were already backwardated, have steepened their inversions. Amid supply chain crunches and inflationary fears, all the commodity markets seem to be signaling that they're worried about future availability of these raw materials and willing to pay a relatively frantic higher price now, urgently, to motivate the goods to come to market as soon as possible.

Inventories of just about everything are historically low. Europe's natural gas storage facilities are only 35% full. Meanwhile, less than a week of global copper consumption is currently available in warehouses, so the April-to-May copper futures spread has flipped to a dramatic 3-cent backwardation. And arabica coffee inventories are at a 22-year low, so coffee futures spreads, which are almost never in backwardation, have flipped with September futures now worth 4 cents less per pound than March futures.

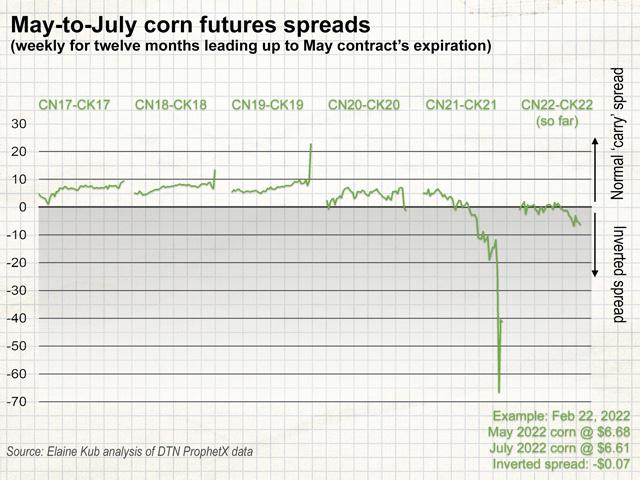

Are the grain markets getting in on this topsy-turvy pandemonium? Oh yes! In years with normal supply and storage conditions, March corn futures are usually about 6 cents cheaper than May futures, and May futures are usually about 6 cents cheaper than July futures. So, with March corn at $6.75 per bushel, we might expect to see May at $6.81 and July at $6.87. Instead, the opposite is now the case, as it has been off-and-on since late January -- the nearby March contract is the most expensive one, followed by cheaper May, followed by cheaper July and so on down the line.

Soybeans, too, have a higher price for the nearby contract ($16.35) than for the deferred July contract ($16.30). The market wants to motivate owners of the grain to bring that grain to end users now, urgently, rather than to pay for storage and look for a higher price in a later timeframe.

This is unusual, but not unprecedented, after a series of growing seasons with imperfect production conditions. In 2021, the March-to-May corn futures spread flipped out of its carry structure in January, and by this time last year, it was inverted at -8 cents. Today, the 2022 May-to-July corn futures spread has been in an inverted structure since November, on roughly the same schedule as the behavior of the 2021 May-to-July corn futures spread, which ultimately traded as wild as -67 cents (on 4/30/21, first-notice day for the May contract, that May contract was $7.40, while the July contract was $6.73).

When grain futures contracts are in their typical carry structure, there is only so wide the spreads will go; they'll generally stay narrower than 10 cents, theoretically limited by the physical costs of storage that commercial grain companies can arbitrage by choosing to deliver physical grain against an expiring futures contract. But when grain futures contracts are inverted, there is no theoretical limit to how inverted they can be. Anyone who shorts these spreads has unlimited theoretical risk.

For farmers who intend to sell grain at an uncertain flat price without any futures hedges, this inverted futures structure isn't too big of a deal. They still have the same price risk as always. They might interpret today's bullish price movement as a signal to reward the market by selling now; or they may pay for storage and wait to sell in July, when the flat prices may be either higher or lower than today's price -- who knows?

But if the farmer is hedged with short futures contracts, then the implications are very serious indeed. If a farmer has a short March futures contract, the inverted futures structure strongly motivates that farmer to deliver 5,000 bushels of cash grain now and simultaneously exit (buy out of) the March futures hedge before the March contract expires, rather than roll the hedge forward into the May contract or the July contract.

It's the rolling of short contracts that's the main concern. Buying out of March at $6.75 and simultaneously re-selling a July contract at $6.65 would mean an instantaneous loss of $0.10 per bushel in the farmer's brokerage account -- better to be avoided.

On the other hand, long hedge holders (end users locking in feed prices, for instance), or long-only speculators, like commodity index funds, finally get to benefit from the futures roll in inverted grain markets. Most of the time, in a normal carry structure, they're the ones getting stuck with those instantaneous losses as they sell out of one lower-priced contract month and buy into the next higher-priced contract.

The traders with the biggest implications of all are the elevators and commercial grain companies with millions of bushels to either store for the next few months and maintain short futures hedges -- and thus be exposed to those potentially unlimited futures roll losses -- or alternatively, to sell physical grain to a frantically bullish end-user, and simply buy out of those millions of bushels of risky futures spread exposure. The March-to-May spread is only inverted by about 2 cents right now, but looking at first-notice day for the March contract coming up on Monday, and looking at the history of how wild these inverted spreads can get, it's clear there's a pretty strong motivation to do just that.

* "Commodity Futures Prices: Some Evidence on Forecast Power, Premiums, and the Theory of Storage on JSTOR," https://www.jstor.org/…

**

Elaine Kub is the author of "Mastering the Grain Markets: How Profits Are Really Made" and can be reached at masteringthegrainmarkets@gmail.com or on Twitter @elainekub.

(c) Copyright 2022 DTN, LLC. All rights reserved.