Kub's Den

Schadenfreude: That Feeling Commodity Producers Get When Bitcoin Tanks

Many people in the Corn Belt and other agricultural regions pride themselves on being "nice." The phrases "Minnesota nice" and "Iowa nice" get plastered on mugs, stickers and t-shirts; farmers from the Canadian Prairies are famously nice; and the cotton-growing regions of the U.S. Delta practice Southern charm. But here in South Dakota, we never bother calling ourselves "nice," so I'll go ahead and admit to something not-so-tender-hearted: Watching bitcoin prices implode over the past three months has given me pleasure, despite a lot of other people's financial pain right now.

This is a form of "schadenfreude": enjoyment experienced from the troubles of others. The German expression translates literally as "harm-joy." And I admit that it's not very nice. But unless you yourself are one of those people losing half your money in cryptocurrency bets, I'm sure you'll understand.

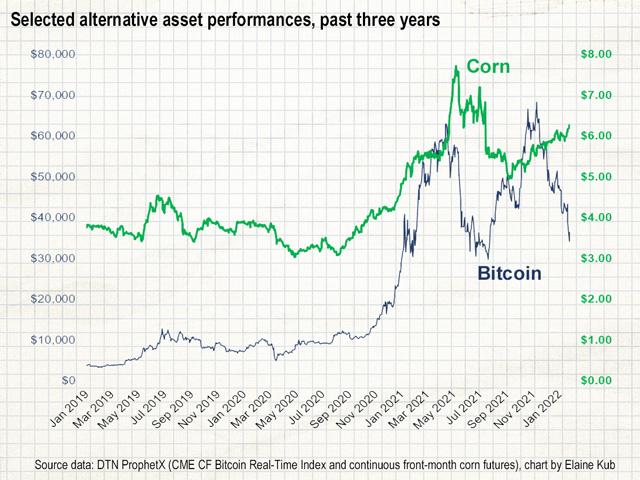

From its high of $68,964 per imaginary token on Nov. 10, 2021, the CME CF Bitcoin Real-Time Index has fallen 52%, which is an even steeper sell-off than the stock market is experiencing right now (the S&P 500 Index is down 8% since the start of the year). In a risk-off environment where investors are spooked about the prices of any assets potentially affected by inflation or interest rate rises in 2022, an impossible-to-value speculative asset like cryptocurrency just isn't very popular anymore.

Meanwhile, commodities keep marching higher. Crude oil is over $95 per barrel, Malaysian palm oil keeps exploring fresh record highs, cotton has moved above $1.20 per pound, and corn, soybeans and wheat are all moving back in the direction of their highs from last year. Of course, those are all real substances -- food, fiber or fuel -- which can be used within the economy to create real value. It's worthwhile to make this comparison between commodities and cryptocurrencies because both sectors attract some of the same investors, when those investors go hunting for volatility and the chances for big returns in alternative asset classes.

P[L1] D[0x0] M[300x250] OOP[F] ADUNIT[] T[]

There's just something more primally satisfying, or perhaps more karmically comforting, in seeing corn at $6.20 than in seeing bitcoin at $62,000. Commodity producers do real work to grow that corn and bring a real substance to real businesses and real consumers. Cryptocurrency traders may have never done anything more demanding than clicking computer buttons in their parents' basements, and their success only depends on how early they got into the pyramid scheme -- buying a piece of nothing in the hope that some other sucker will pay more for that nothing later.

To be sure, some of these traders have been massively successful. If I'd bought 100 bitcoins when I first heard about the idea back in 2012 (oh, if only), when they were trading for $13, and if I hadn't cashed out or been the victim of theft by hackers, and if I was still holding those 100 bitcoins, my "wallet" would be worth over $37 million today. Which is down from the $68 million it would have been worth back in November, but still. As speculative plays go, the bitcoin speculation has been spectacular. For some people.

The majority of cryptocurrency "investors" didn't get in on this particular pyramid scheme until much later, and in fact, some watchers estimate more than a third of the circulating supply of bitcoins are now underwater -- worth less than the price at which they were originally purchased. Let's say a 20-something fast-food worker put $10,000 (their life savings) in bitcoin during the hype last spring or fall. Today, their wallet would be worth less than $6,000, assuming they encountered no technical glitches in the process of cashing it out. At least if you lost money on Dutch tulip bulbs in the 17th century, you could still plant a pretty flower.

The real fortunes in cryptocurrencies, however, are gained or lost by the "miners" who program and operate the expensive, electricity-gobbling supercomputers running the cryptographic (encryption-solving) blockchain technology which ultimately underpins the whole cryptocurrency system. In Kazakhstan, for instance, cryptocurrency miners have swarmed the country's coal-powered electricity grid so badly, they've been causing rolling blackouts for everyone else in the country. It's hard to shed a tear for these people when their profits halve.

I want to make it clear that I'm not an anti-blockchain luddite -- I'm delighted there are successful applications of blockchain technology already being used to ease the paperwork and enhance the trust of international agricultural trading. And someday we may see the U.S. Federal Reserve issue their own digital currency, which they are researching (https://www.federalreserve.gov/…), to make payments smoother, if they can do so while maintaining the stability of the financial system. But neither of those applications has anything to do with the wild, bubbly price of speculative bitcoin and other cryptocurrencies.

Who knows? The bitcoin chart may turn back around and reach $100,000 someday, or $1,000,000. When there is no underlying economic calculation to find an asset's fundamental value, then its value will always be whatever the next person is willing to pay. But if it doesn't, then the real implications for the financial markets are likely to carry through the year 2022. Inflation is an ongoing phenomenon, and the Federal Reserve may hike interest rates by 0.75 percentage points by the end of the year. Some asset classes do better than others in an inflationary environment, like real estate (which is, you know, a "real" thing that earns higher cash rents when prices rise) and some stocks, if they represent companies that sell "real stuff" at newly inflated prices. The best inflation hedge, of course, is the "real stuff" itself: commodities. Corn, soybeans and wheat can all be turned into higher-priced fuel, higher-priced meat and higher-priced boxes of cereal in an inflationary environment.

In the comparison between cryptocurrency and grains, it doesn't get more imaginary than bitcoin, and it doesn't get more real than corn.

Elaine Kub is the author of "Mastering the Grain Markets: How Profits Are Really Made" and can be reached at masteringthegrainmarkets@gmail.com or on Twitter @elainekub.

(c) Copyright 2022 DTN, LLC. All rights reserved.