Kub's Den

Higher Metals Prices Add to Ag Supply Chain Worries

The only hot commodity headline this week -- at least until Friday's World Agricultural Supply and Demand Estimates (WASDE) report is released -- is a military coup in the west African country of Guinea, which is expected to drive up the global price of aluminum.

Guinea is the world's leading provider (25%) of high-quality of bauxite, the starting ore for aluminum production, and there is concern among metals traders, mostly in Russia (which gets 50% of its bauxite from Guinea) and China (which gets 55% of its bauxite from Guinea), that the new Guinean military junta will renege on previously priced bauxite contracts and demand more money for the stuff.

This concern drove benchmark aluminum futures prices up almost 2% at the start of this week, and the front-month Comex aluminum contract closed at $2,788 per metric ton on Tuesday.

But aluminum prices were already on a skyward path, so what's another dollar or $30 to maintain the momentum that metals have displayed since mid-2020? Copper prices have pulled back since their May 2021 high of $4.88 per pound, but aluminum futures still have a way to go before they match copper's gains in percentage terms.

Agricultural producers are of course familiar with volatile commodity prices getting suddenly whipped around due to geopolitical surprises from halfway around the globe. There is a vague expectation that all commodity sectors tend to experience relatively high or low prices at roughly the same time, due to global raw material demand or inflation expectations or simply the self-fulfilling prophecy of investment flows.

However, the correlation between aluminum and corn prices, for instance, isn't particularly tight on a day-to-day basis.

P[L1] D[0x0] M[300x250] OOP[F] ADUNIT[] T[]

Nevertheless, the agriculture industry may see these skyrocketing aluminum prices and feel like it's important to watch -- not as a bullish story about commodity prices, but as an alarming story about business conditions, when the agricultural machinery supply chain is already tightly constrained and the price tags are already high.

Aluminum isn't the most common metal found in agricultural machinery. Some pieces of equipment probably contain no aluminum at all -- like augers, rollers, and chisels. But consider anything that requires control devices or lightweight alloys -- like sprayer booms, aluminum hopper trailers, the wheel hubs on the trucks that haul the grain or all the various little valves and other engine parts that may include some aluminum.

We may start to worry that rising aluminum prices could make an already expensive crop production input -- the fixed costs of buying machinery -- even more expensive.

There are two other influences that may be juicing up equipment prices right at the same time that raw metal prices are rising. Purchasing demand from farmers is elevated in a year when grain prices are relatively high, and simultaneously, supplies are scarce while the global supply chain is still a mess of backed-up ocean freight and chip shortages at manufacturing plants worldwide.

Of course, just because it may cost more to buy the machinery to grow the grain, the actual grain prices won't necessarily rise in response. It's like when grocery shoppers get worried about paying more for their Froot Loops just because the price of wheat has gone up -- in reality, the proportion of the retail price tag that can be traced back to just one of the many raw materials (wheat flour) inside a box of Froot Loops is miniscule compared to the majority of consumers' food dollar spending that goes to food processing, marketing, wholesaling, distribution, and retail.

Similarly, only a small fraction of machinery costs can be traced back to the prices of actual raw aluminum, iron, glass or rubber.

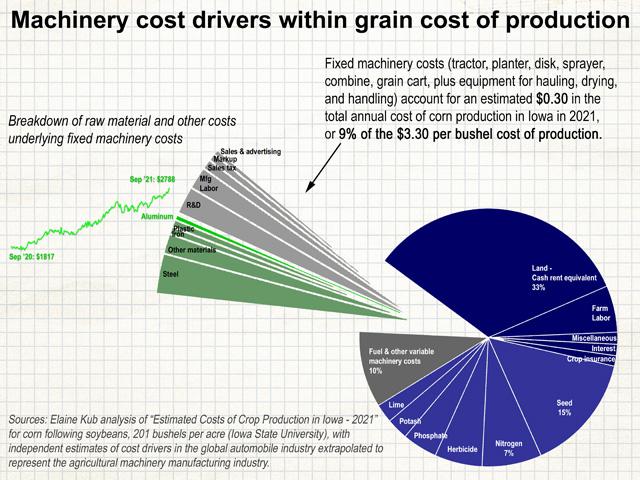

Fixed machinery costs (the dollars it takes to own or lease tractors, planters, disks, sprayers, combines, grain carts, augers, grain bins, dryers, hopper trailers and all the other pieces of equipment that are required for grain production) account for an estimated $0.30 per bushel in the total annual cost of corn production in Iowa in 2021, according to the Estimated Costs of Crop Production prepared by Iowa State extension economist Alejandro Plastina. That's about 9% of the overall $3.30-per-bushel cost of production, assuming the Iowa farmer in the example is growing corn after soybeans and achieves a yield of 201 bushels per acre.

Of that 9% of overall expenses that gets paid for farm equipment, how much is influenced by the actual cost of the metal? Estimates from the automobile manufacturing industry suggest that somewhere around half of the price of an automobile can be traced back to the costs of the raw materials. Let's assume it's about the same for the agricultural machinery manufacturing industry.

Ag equipment doesn't need as much lightweight alloy as car bodies do, but still, let's assume that the breakdown of those raw materials is about the same -- 47% steel, 8% iron, 8% plastic, 7% aluminum, 3% glass and 27% "other materials." In that case, the raw material value of the aluminum that goes into a farm's machinery fixed costs accounts for something like 0.3% of the farm's total expenses. That's less than one half of 1% of the cost of producing grain.

So even if the price of corn was determined by its cost of production (which again, it's not, except perhaps in the very long-term global sense), then this coup in Guinea may be worth inches of newspaper column space, but it's not worth much added on to the cost of producing a bushel of corn.

Don't let it keep you up at night.

At least, don't let this week's aluminum price movement keep you up at night. But the ongoing supply chain disruptions? That's another matter, worthy of serious thought and advance planning to keep your business running through the end of this year and into the next. As Progressive Farmer Senior Editor Joel Reichenberger pointed out (see "How to Get Through Short Supply of Parts During Busy Time" at https://www.dtnpf.com/…), equipment orders that used to have a 12-week lead time may now be looking at a 12-month lead time. And by then, who knows what the raw material price tags may be?

Elaine Kub is the author of "Mastering the Grain Markets: How Profits Are Really Made" and can be reached at masteringthegrainmarkets@gmail.com or on Twitter

(c) Copyright 2021 DTN, LLC. All rights reserved.