Kub's Den

Strong New-Crop Basis Bids Reflect Supply Concerns

It's early August 2021, before row-crop harvest gets going in North America (48% of Texas corn is currently considered mature), and here's a snapshot of what corn basis bids look like: The ADM corn-processing plant in Cedar Rapids, Iowa, is bidding $1.25 over the September futures contract for spot delivery (a $6.75 cash corn price tag), barge loaders in Illinois are bidding $0.75 over September ($6.25), and some cattle feeders in Colorado are still willing to pay above $7 per bushel for corn. Clearly, grain buyers remain persistently desperate to get their hands on whatever old-crop corn remains available in the country.

However, those are spot bids. What about the market for new-crop grain -- the stuff that's still maturing out in the fields, the stuff that's already being committed to big export sales contracts in the marketing year that begins in less than a month? Any efficient market should arrive at a price that communicates all the knowable information about an asset, like a commodity's prospects for supply shortages and higher prices or demand drops and lower prices. So, looking at cash grain traders' bids and offers can help us determine what information they know about upcoming supply and demand. The early August timeframe is an interesting time to do this, because it's about the time when farmers and their agronomists (and the grain merchandisers who ultimately want to buy the grain) can physically go out into the fields and count ears and kernels per ear and get a sense of what yields might really be. If those originators haven't booked as much new-crop grain yet as they would typically like to have on the books before harvest, now is the time when they might start to express their competitive spirit in stronger basis bids.

As it happens, traders do seem a little nervous about 2021's new-crop corn, at least in the Western Corn Belt. At the same Cedar Rapids ethanol plant, new-crop corn bids are typically about $0.15 to $0.30 under the December futures contract during early August, but this year their posted new-crop bid is $0.12 under the December contract. At a central Nebraska co-op elevator where the new-crop basis bid usually lingers at an almost automatic bid of $0.45 under the December, this year they're already pushing new-crop basis as strong as $0.20 under the December, a value that has been stair-stepping stronger this year, nickel by nickel.

P[L1] D[0x0] M[300x250] OOP[F] ADUNIT[] T[]

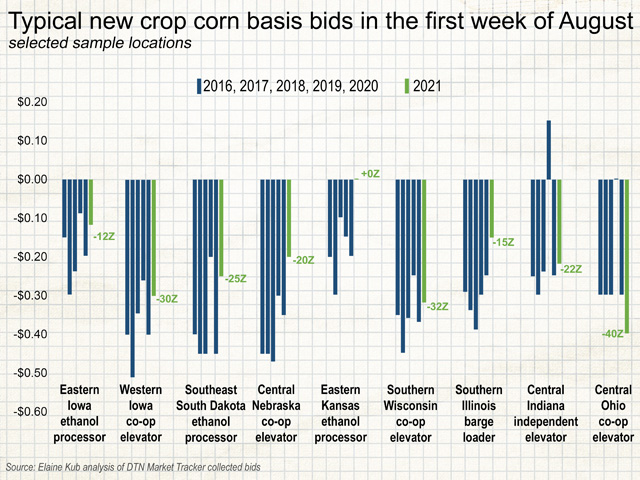

At a variety of random locations that I sampled, new-crop basis bids are relatively strong compared to typical bids for this time of year. It's not a very dramatic indicator yet. Not like, say, in August 2019 when elevators in Indiana and Ohio were already bidding double digits over the December futures contract to try to attract scarce bushels. As the 2019 Indiana example demonstrates, local cash markets for grain really do reflect the physical reality of supply and demand. Looking at basis bids can tell us a story about what's really happening with a crop. In 2019, that story was a lack of planted acreage in the Eastern Corn Belt and the Dakotas due to excessive moisture during the spring planting season.

In 2021, we may be reading a similar story about relatively scarce new-crop bushels, but from an opposite cause -- plenty of acres but a lack of moisture. Currently, 26% of the Midwest remains in moderate, severe or extreme drought, according to the U.S. Drought Monitor, and much of that is centered in the massive corn- and soybean-growing regions of Iowa, southern Minnesota and southern Wisconsin. Farmers are uncertain about how many bushels they will harvest and have available to sell in October and November, and the recent volatility in grain prices has likely made them even more reluctant to sell bushels ahead of harvest. This means grain buyers have had to be aggressive with their new-crop bids. Even areas that aren't in drought, like Kansas and southern Illinois, but which draw grain from drought-stricken regions, are posting unusually strong new-crop basis bids, generally about 15 or 20 cents stronger than "normal" for this time of year.

On the other hand, in the Eastern Corn Belt, where they've had suitable soil moisture all during this growing season and they continue to see good precipitation forecasts during this timeframe when the crop is filling out with its final weight, new-crop basis bids are currently ranging from normal to weak. At one central Ohio co-op elevator whose bid history I sampled, they seem to have a policy of almost always bidding $0.30 under the December contract before harvest, but this year they're so confident of seeing abundant new-crop corn bushels, they've dropped their bid to $0.40.

Again, this local cash market behavior is all a reflection of physical reality, which can also be measured by USDA's crop condition ratings (80% of Ohio's corn is rated good or excellent, while only 30% of South Dakota's corn is rated good or excellent), and the observations of the DTN Digital Yield Tour powered by Gro Intelligence's real-time yield maps, which incorporate satellite imagery, rainfall data, temperature maps and other public data. So far, results from the DTN Digital Yield Tour are suggesting persistent drought in the Dakotas may have dropped corn yield potential by 20 bushels per acre on average. It's likely the results from the Eastern Corn Belt will be much more favorable, which you can read about at https://spotlights.dtnpf.com/… while the tour continues through this week.

If the information you find there affects the new-crop outlook for the grain buyers and sellers in your region, you can be sure it will all get reflected in the local basis bids that will continue to evolve even before the first load of warm, new grain arrives at the elevator.

Elaine Kub is the author of "Mastering the Grain Markets: How Profits Are Really Made" and can be reached at masteringthegrainmarkets@gmail.com or on Twitter @elainekub.

(c) Copyright 2021 DTN, LLC. All rights reserved.