Kub's Den

Beef Market: Drought and Profit Margins Keep Prices High

In the commodity markets, we often say "the cure for high prices is high prices." Either the tantalizing profits will motivate a huge surge in production of that high-priced commodity (and then the fresh oversupply will bring prices back down) or the forbiddingly expensive price tag will discourage end users from buying so much of the stuff (and then the drop in demand will bring prices back down). Either way, hot commodity prices never stay flat for very long.

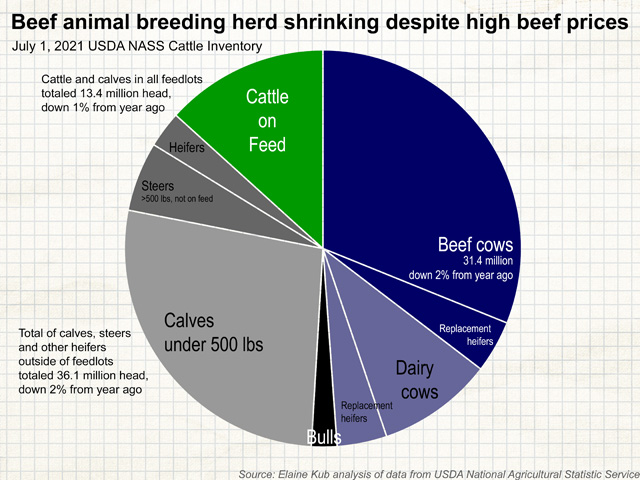

The exception in 2021 seems to be beef, with wholesale prices still 36% higher than they were a year ago, and yet the country's herd of beef cattle actually shrunk 2% between July 1, 2020, and July 1, 2021. In this market, there may be no easy "cure" for high prices, and the condition could persist for a few years due to two structural reasons.

The first very obvious reason why the cattle industry hasn't been expanding its production of beef animals is drought. No matter how much the nation's ranchers may want to increase their herd sizes and deliver more animals to market, it's simply impossible when 65% of the West is suffering extreme or exceptional drought. In the state of Washington, only 4% of pasture and range is rated in good condition and exactly 0% is rated excellent. In the High Plains (North Dakota, South Dakota, Wyoming, Colorado, Nebraska and Kansas), only 28% of cattle country isn't in some sort of abnormally dry or drought condition. The land simply cannot sustain its usual abundance of grazing animals this summer. Miserable ranchers are forced to make the anguishing decision to liquidate portions of their herds, and total U.S. beef cow slaughter has been running 12% above its usual pace, although it's much heavier in specific drought-stricken regions.

P[L1] D[0x0] M[300x250] OOP[F] ADUNIT[] T[]

So, that's one disconnect between the market signal and the response -- it wouldn't matter what price the beef market was signaling, the industry right now simply is not able to respond with overall numbers when drought is this widespread.

There is another disconnect between the beef market's prices and beef animal production -- the market may be giving a signal (consumers buying hamburger for $5.00 per pound and wholesalers selling choice boxed beef for roughly $2.70 per pound), but that signal isn't getting passed to the right people. Packers are pocketing those high beef prices, profiting hundreds of dollars for each fed steer or heifer they process, but the profit doesn't make it farther down the supply chain. Fed cattle prices are $20 per hundredweight better now than they were during the COVID-19-challenged meatpacking environment of a year ago, but they're not what they could be, according to historical price relationships. During the 10 years leading up to 2020, live cattle futures prices tended to average about 60% of the price of choice boxed beef per hundredweight. In April and May of 2021, when choice boxed beef was $300 per cwt (or more) and fed cattle were only bringing $115 per cwt, this relationship dipped below 40%. At today's boxed beef prices ($267 per cwt), we might expect to see live cattle prices at $160, but they are instead stuck below $125 per cwt (46%).

Things have changed in the meatpacking industry and no doubt there are legitimate reasons why the profit margins throughout the industry shouldn't be expected to exactly match those of 10 years ago, but some of these changes could, nevertheless, be addressed. According to the White House's Fact Sheet that accompanied the July 9 Executive Order on Promoting Competition in the American Economy, "Consolidation ... limits farmers' and ranchers' options for selling their products. That means they get less when they sell their produce and meat -- even as prices rise at the grocery store. For example, four large meat-packing companies dominate over 80% of the beef market, and over the last five years, farmers' share of the price of beef has dropped by more than a quarter -- from 51.5% to 37.3% -- while the price of beef has risen."

For traders, of course, the question is not about which price level would be fair or what prices should be, but rather what prices will be. Reductions in the beef animal breeding herd have already cast the die for production quantities through the next few years. Mama cows who are culled this summer won't have a calf next spring, and expectations for the 2022 calf crop should be correspondingly lowered. This, in turn, means fewer market-weight steers and heifers should be expected in mid-2023, keeping supply tight.

The dairy herd has been expanding by 2% at the same time the beef herd has been contracting, but calves from the nation's 9.5 million head of milk cows cannot fully fill the long-term void that will be left after this drought.

There may be implications for the feed markets too -- specifically corn futures -- but when it comes to demand for U.S. feed grains, a slightly lower number of domestic cattle on feed in 2022 and 2023 could be outweighed by the continued expansion of poultry feeding in this country, not to mention the chances of strong feed grains exports to other countries that are feeding their own expanding herds of animals.

Meanwhile, the highest heat in the beef market may have peaked back in early June, when choice boxed beef (wholesale) hit $340 per cwt (well short of the May 2020 record high of $475, but impressive nevertheless). It has since softened to $267 per cwt in late July. However, the benchmark wholesale prices for 90% lean ground beef remain as strong as they were in June but may now be plateauing beneath $280 per cwt. Perhaps there is only so much a grocery shopper is willing to pay for beef, no matter how delicious it is and no matter how much of that price ever gets passed back to the producers of the animals. It may not be possible for cattle producers to cure high prices with higher production this year, but as always in a commodity market, it could be consumers who moderate the prices with more hesitant demand.

Elaine Kub is the author of "Mastering the Grain Markets: How Profits Are Really Made" and can be reached at masteringthegrainmarkets@gmail.com or on Twitter @elainekub.

(c) Copyright 2021 DTN, LLC. All rights reserved.