Kub's Den

ESG: Another Acronym for Ag to Know

The easiest way to attract investment in a company today is to convince investors the company is operating sustainably and making sustainable long-term decisions, and therefore deserves to be included in the fashionable "ESG" category of investments (screened for Environmental, Social and Governance considerations). The amount of money allocated to ESG-mandated strategies has more than tripled worldwide over the past 10 years -- pegged at over $100 trillion in 2020 -- and the accounting firm Deloitte estimates ESG-mandated assets could make up half of all investment funds in the U.S. by 2025. This is customer driven: polls show over 70% of individual investors say it's important to align their investments with ESG ethics, but it's more like 95% among millennial investors.

The financial press is saturated every day with ESG coverage -- who's in, who's out -- but I've rarely seen the acronym used in farm media ... yet.

One of those rare mentions can be seen here: https://www.dtnpf.com/…).

Big agriculture firms are justifiably obsessed with proving their ESG bona fides, of course (ADM, Bunge, Cargill, General Mills, McDonalds, et al.), especially if they are publicly traded or even just anxious about rubbing their customers the wrong way. Most primary agricultural producers in the United States, however, don't face those same pressures. Sole proprietorships and family-owned LLCs don't have to worry about highlighting ESG measures in their annual report to attract -- or just not lose -- capital. Nevertheless, ag commodity prices are influenced by investors' behavior, so it's useful to know what trends and tides are surging among investors. Moreover, sophisticated ag businesses, both large and small, may find the ESG framework helpful for communicating the good things they're doing.

There is no universally recognized format of what exactly ESG is or how it should be measured, but common considerations include:

ENVIRONMENTAL

-- How does the company's supply chain affect biodiversity where it operates?

-- How does it affect climate change?

-- How does it address pollution and the conservation of natural resources?

P[L1] D[0x0] M[300x250] OOP[F] ADUNIT[] T[]

-- How does it preserve water security?

SOCIAL

-- Does the company adhere to ethical labor standards and preserve human rights?

- -What are the safeguards for workers' health and safety?

-- What are the safeguards for customers' health and safety?

-- How does the company interact with the communities where it's located?

GOVERNANCE

-- What are the safeguards against corruption at the board and management level?

-- What are the company's risk management policies?

-- Does the company pay its ethical fair share of taxes?

The main idea is that companies who have thoughtfully prepared policies on these topics will be better able to sustain their operations through the long term; protecting themselves from legal, financial and reputational risks. Although a company's investment in worker safety or community relations may not look maximally profitable in just one quarter, their ESG investments will optimally pay off through a 5-, 10- or 50-year timeline as they prevent lawsuits or prevent the destruction of the civilization in which the company operates.

More specific ESG considerations could range anywhere from the recruitment of migrant workers to transparent product labeling, depending on who is doing the ESG assessment. Tracking down all these impacts can be extremely difficult, especially for agriculture companies who rely on complex supply chains. For now, it's basically every company for itself, promoting the good things it already does, with no official ruling body to say who is or isn't "ESG" enough.

For instance, Coca-Cola gave its 2019 annual report the outright title "2019 Business & Sustainability Report," with sections for "Climate Resilience in Action," "World Without Waste," "Water Leadership" and "Sustainable Agriculture," putting the usual tables of financial data as somewhat of an afterthought way at the end.

If an individual grain producer were going to prepare an ESG report to build good relationships by communicating with landlords, perhaps the report might highlight things like no-till practices and soil sampling to demonstrate efficient soil and nutrient management and maybe the civic/volunteer involvement of the business owners to show how they've built a strong local community.

Of course, being able to say nice things doesn't really prove anything. Consider the example of the mining company Rio Tinto, which was able to check all the ESG boxes that investors wanted, but then in May of 2020, while prospecting for a new source of iron ore, blew up some ancient Australian caves of great significance to local Aboriginal people. Australia's sovereign wealth fund and other influential investors subsequently called for, and succeeded in getting, the CEO and other responsible executives fired. The lesson: companies today must not only say they will behave in all these ethical, sustainable ways, they must actually do so or face financial consequences.

Note, of course, that the actual price of iron ore (or any other commodity) doesn't hinge on what ESG measures are taken or not taken by the companies that produce those commodities. It will still always be about supply and demand. Sustainability practices may add to the costs of production and challenge the profitability of the producers, but they largely don't change supply. Meanwhile, consumers' demand for commodities continues to grow. ESG investing is a big concern for oil and mineral mining companies, which are generally large publicly traded commodity producers that depend on the stock markets to finance their projects. But, even in those metal and energy commodity industries, ESG still doesn't really touch the price of the commodities themselves. No one, to my knowledge, has tried to make a lump of coal or a bushel of soybeans answer an ESG questionnaire about the ethics of its social interactions. That day may come, however.

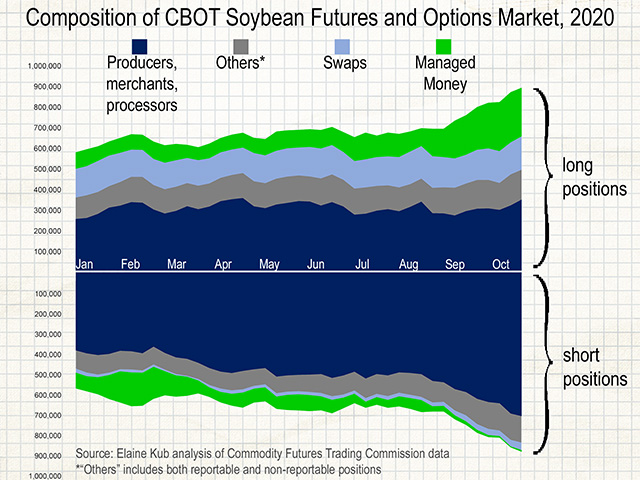

Agriculture commodities, in fact, have had no trouble attracting interest from speculative investors in recent months. The CBOT soybean futures market, for instance, reached a milestone at the start of this month when its total open interest grew to over 1,000,000 contracts for the first time in history. All of this speculative participation -- with managed money traders currently holding 21 long soybean futures contracts for everyone short soybean futures contract -- may eventually add volatility to the prices when the eventual sell-off occurs. But for now, it's good to have those investors playing along and not demanding a full ethics report before chasing profits in the commodity markets.

Elaine Kub is the author of "Mastering the Grain Markets: How Profits Are Really Made" and can be reached at masteringthegrainmarkets@gmail.com or on Twitter @elainekub.

(c) Copyright 2020 DTN, LLC. All rights reserved.