Deworming the Herd

Put the Brakes on Parasite Resistance

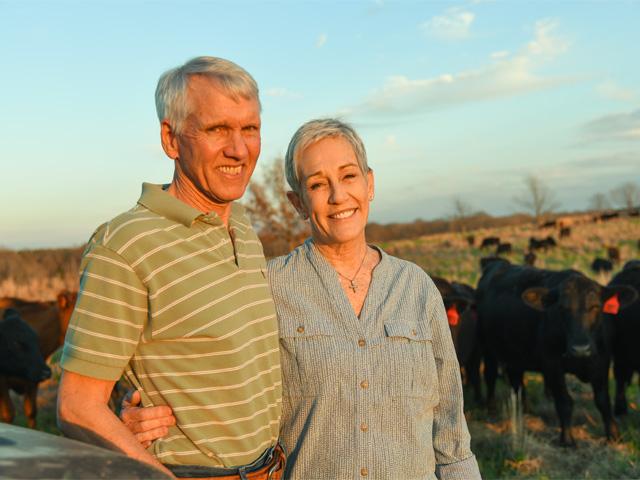

When veterinarian Christine Navarre lectures about parasite resistance, she finds a receptive audience in livestock producers like Cooper and Katie Hurst.

Ten years ago, the husband-and-wife team bought 200 goats to help clear a new bull pasture, and despite conscientiously using the globally recognized method of eye scoring to check for parasites, they lost goat after goat when dewormers didn't work. Concern grew they would see the same thing happen in the cow herd, without taking steps to prevent resistance.

The Woodville, Mississippi, couple, followed the lead of Navarre, Extension veterinarian for Louisiana State University (LSU), and incorporated a new approach to parasite control into their cattle operation. The new approach to deworming is focused largely on not deworming-- at least not by the calendar.

"We're trying to break the habit of deworming," explains Cooper. "We strategically deworm first-calf heifers. They're trying to rebreed, they're losing teeth, and they're still growing. We'll deworm them after their first calf, but before they rebreed."

Some females can't make it in their system. In those cases, they deworm them, and sell them. For weaned calves, the approach to deworming depends on whether they stay on the farm for preconditioning. Typically, the Hursts retain ownership of calves through harvest. Calves often go to Texas or the Flint Hills of Kansas to gain on grass before heading to the feedlot. In the stockering phase, deworming is likely but not automatic.

FORAGE MANAGEMENT'S ROLE

The Hursts emphasize that the internal parasite control program for their cattle herd is part of an overall system that includes rotational grazing, adapted genetics and stockmanship.

The headliner is forage management. The Hursts prefer the term "Adaptive Multiple Paddock" (AMP) grazing, but it is also known as "high density" or "mob" grazing. They use multiple paddocks and move large numbers of cattle through them rapidly.

P[L1] D[0x0] M[300x250] OOP[F] ADUNIT[] T[]

"It is a big help in internal and external parasite control," says Hurst of their forage management program. "The paddocks have a long rest and recovery stage, never less than 30 to 40 days, and as long as 90 to 100 days. That helps break the life cycle of worms."

When they do hatch, parasites struggle to climb more than 3 or 4 inches up a blade of grass. With that in mind, the Hursts try to keep the forage at least 6 inches high, in most cases higher. That means cattle aren't ingesting parasites when they graze.

To make their grazing program as efficient as possible, they often run their whole cow herd in one group -- about 225 to 250 animal units. At times, they add in the replacement heifers and stockers. Stocking density runs from 30,000 pounds to 150,000 pounds an acre. Temporary electric fencing cuts down on the time it takes to set up and take down paddock fences and move cattle.

The Hursts usually move cattle daily, and at times twice or even three times. It all depends on grass height and cattle condition.

Katie says, "A lot of people say it is too much work. That's not true at all. It is so easy. It takes us 15 to 20 minutes to build a paddock and move the cattle." Cooper adds, "They're waiting at the gate." This is also where their insistence on low stress cattle handling shows. Often, visitors don't even realize the cattle have changed paddocks because they move so quietly.

UNEXPECTED BENEFITS

The Hursts have been practicing high-density grazing for 12 years, and they monitor both their forages and cattle closely. Over that time, they've seen positive changes beyond parasite control, including a reduced need for hay.

The pair say they're currently down to one roll of purchased hay per cow per year.

"We can easily get to January on stockpiled Bermuda, Bahia, dallisgrass, Johnson grass and broadleaf signal grass," says Cooper. "And every forb known to man," adds Katie.

In December or January, they supplement cows twice a week with 1 to 2 pounds per head of cottonseed pellets. Replacement heifers get a pound of pellets a day. At this time, cattle will also be grazing winter forages, some broadcast and some drilled. These typically include ryegrass, cereal rye, hairy vetch, oats, triticale, peas, clovers, and brassicas.

In addition to savings on hay, the Hursts say they haven't used any synthetic fertilizer since they started AMP grazing. They simply rely on the manure and urine of the cattle to supply the fertility needs of their pastures.

GENETIC ADVANTAGES

In addition to their carefully managed grazing system, the Hursts are changing the genetic makeup of their herd.

Members of U.S. Premium Beef, they were accustomed to high percentages of Prime and Certified Angus Beef with their growthy commercial Angus calves. However, they didn't feel those cattle fit their lower input system and have been converting to a Red Angus -- South Poll cross. South Poll cattle are smaller, more heat tolerant and are a quarter each Hereford, Senepol, Barzona, and Red Angus.

"We've already seen the amount of supplement we have to buy go down by a third," says Cooper. "We've not only gone from a 1,400-pound cow to an 1,100-pound cow, we've gone to the right type of 1,100-pound cow."

Three years into the genetic shift, there are challenges. Many of their cows are still black and can't handle their 45-day breeding season, which they've changed from the cooler months to June and July. The shift was to ensure the herd was calving during peak forage availability. Conception rates dipped below 80% last year. Those females that didn't fit the new system are being moved back into a fall calving and breeding season and sold.

ADAPT TO THE ENVIRONMENT

While the Hursts give a great deal of the credit for their reduction in the use of dewormers to their grazing system, LSU's Navarre cautions that a rigid, scheduled approach to rotational grazing can actually make parasite problems worse. Parasites may have a 21-day life cycle in the lab, she explains, but that may not be the case in the pasture.

"That 21-day cycle is if you have consistent rainfall and a consistent temperature," she says. "If you're set on rotating every 45 days, for example, then depending on the rainfall, those worm eggs may not hatch at the same time. If it is dry, and then it rains, they may hatch all at once, and you may end up turning cattle in when the parasites are most active. There is no magic formula. Rotate based on your grass conditions and monitor parasites with fecal egg counts.

"You have to be flexible enough in your management to deal with weather extremes and changes in your environment," Navarre adds. "Be prepared to step in and rescue animals with purchased feed or animal health products if needed."

(c) Copyright 2022 DTN, LLC. All rights reserved.