A Beginning Farmer's Bet on the Farm

Author Explains How Family Farmers 'Bet the Farm' in First-Person Story of an Iowa Farm

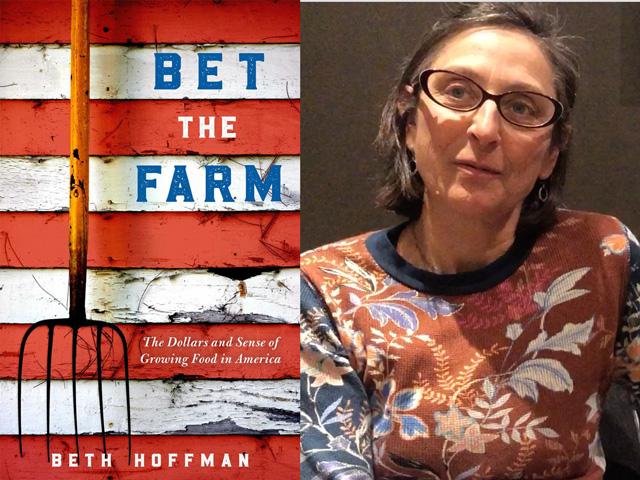

OMAHA (DTN) -- Beth Hoffman thought a long history reporting on agriculture would give her a good insight about taking over a family farm operation. But the journey over her first couple of years in Iowa inspired her to write a book on the experience.

Hoffman draws on her own knowledge about the history of agriculture and the food industry but builds the story around her own personal account about moving from a teaching position in San Francisco to taking over a small family farm in Iowa with her husband. Moving to the farm helped Hoffman better explain some of the misconceptions about agriculture and the real day-to-day problems of a couple trying to run essentially a start-up business on a farm with more than a century of history behind it.

Her account, "Bet the Farm, The Dollars and Sense of Growing Food in America," came out last October.

DTN/Progressive Farmer visited with Hoffman late last month during the National Farmers Union annual meeting in Denver.

Hoffman's book details the story of moving with her husband, John Hogeland, from San Francisco in 2019 to take over the Hogeland family farm in southeast Iowa. Beth and John were both 50 years old when they become beginning farmers.

Beth grew up in New Jersey, just across from Manhattan. She lived in several parts of the country before taking up journalism, moving to California and becoming an associate professor in media studies at the University of San Francisco. John Hogeland had deep farming roots in Iowa, but had left the farm to become a technical writer as well as a chef and butcher in Wyoming and later California, including working for 11 years at Whole Foods.

The agricultural journalist met the Iowa farm native when they became neighbors in 2007. Beth said John told her, "The minute I met him that he had just visited Iowa with his kids, and he loved it, and he was going to move back as soon as they were grown." She added, "I didn't think a whole lot about it at the time, but we ended up moving there later on."

John's Dad, Leroy, was the fourth generation on the farm. John became more determined to return to Iowa and farm after his mother passed away in 2014. After his youngest child graduated school, John and Beth were able to make the move.

Hoffman has a 25-year background as a journalist who covered food and agriculture, with a focus on areas such as the environment, sustainability and cultural aspects of food. Her work has been on NPR, Forbes and several other outlets. She had taught and wrote about food while lecturing at the University of California-Berkeley. Hoffman thought that gave her some insights into farming.

Beth and John moved to Iowa in 2019, and after completing a lease on the farm, started operating it that March. She quickly learned how much more there was she did not know.

"As soon as we had completed the leasing of the farm, it was pretty immediately apparent to me that the actual financial issues were a lot more of an immediate problem on the farm level than were the environmental issues," Hoffman said.

Leroy Hogeland had raised corn, soybeans and cattle on the 530-acre farm near Lovilia, Iowa -- about an hour southeast of Des Moines. The couple decided not to grow row crops and instead to raise grass-fed beef and goats as well as a few orchard trees. A whole section of the book is about the transition as John Hogeland negotiated a lease on the ground from his father who had operated the farm for the past 50 years.

Former Des Moines Register columnist and "Iowa Boy" Chuck Offenburger wrote about Beth and John's farm transition, including an excerpt from the book when Beth describes some of the conflicts that came up as Leroy Hogeland agreed to transition the farm to his son. Leroy had some demands on how the farm should be run before he'd sign a lease.

P[L1] D[0x0] M[300x250] OOP[F] ADUNIT[] T[]

The book excerpt:

"'Well, it's my farm, and this is the way it's going to be,' Leroy continued, slamming his fist on the table.

"No one who was present remembers exactly what happened next, but more fists slammed and a few obscenities flew before John's sisters stormed out in disgust. 'You don't want me to farm; you just want to tell me what to do,' John recalls saying as he walked out the back door following his older siblings."

Hoffman, from her own experiences, was able to bring in a mediator who helped work out some of the family dynamics. She noted there are few people in agriculture who help mediate farm transitions, but it is one of the biggest issues in farming.

As Hoffman began the journey of running family-farm operations with her husband, she said her eyes were more open to how large-scale challenges in agriculture are symptoms of actual farm-level problems. Even with some personal savings and ready access to more than 500 acres, Hoffman's book shows it can be tough to make ends meet. Finances, managing time and managing labor become more obvious issues.

"Those problems come down to the finances, finding some stability -- because the fluctuations of markets and what you can sell -- creates a lot of upheaval. Farmers are always looking for some kind of stability."

Hogeland and Hoffman also have questions about who will eventually take over and how they will keep the focus of the farm on regenerative practices.

"So, these issues became much more clear to me," Hoffman said. "And so, the book became really focused on, first the financial part, but also how we address these other issues."

Going beyond her own farm operation, Hoffman reflects on the difficulty others face trying to get into farming.

The book has a chapter about the cattle labor and the couple trying to find a locker for their grass-fed cattle. Then the pandemic hit when the couple was ready for some cattle to go for processing. Yet, the farm has come out of the other side of the pandemic with a couple who are no longer novices.

"Now we have a system down a little bit because, back then, we were rookies, and the pandemic started," Hoffman said. "So, we had a lot against us when we thought we were ready for the cattle to come in."

John and Beth have about 40 cow-calf pairs and another 25 or so yearlings. They began moving to a grass-fed operation, which caused them to adjust how they market cattle. Just taking cattle to a local sale barn seemed convenient, but they didn't feel they were getting paid for the labor and management involved to produce grass-fed beef.

"We thought, initially, we would sell out of the sale barn because we have one locally, and a lot of places don't anymore," Hoffman said.

She added, "The labor mandated from moving cattle every day -- the difference between that and what John's dad did, which was having the cattle hang out in the same area for weeks -- that labor difference was so extreme that we had to figure out another way to sell them."

Since taking over, Hoffman said, the couple has been trying to create a clientele with more direct marketing and sending their finished cattle to a local meat locker. Beth indicated there was a private effort underway in Iowa to try to more broadly market grass-fed beef from producers in the state.

"We are really hoping that is going to solidify," she said. "We just don't want to have all of our eggs in that one basket."

As far as the goats, Hoffman said they aren't certain about the market yet for the goats, but they are useful for other means.

"The goats are just really effective at clearing brush and invasive weeds, but we will be selling to different kinds of niche markets," Hoffman said.

Chronicling some of the financial, labor, market and environmental conditions and challenges on the farm, Hoffman highlights there is no silver bullet to changing the food system.

"The way food travels to our table -- most often through a long, convoluted chain that yields the farmer little -- has evolved over hundreds of years and will not be untangled without attention to the whole web of issues it has created."

Hoffman shortly later adds: "We need to move away from the romantic tales of farming to understand that while farmers feed people and take care of land, they also need to be able to take care of themselves and their families. Instead of idealizing the self-reliant, self-sacrificing farmer, toughing it out in the field alone and beating her competitors, farmers have to know that we can work together -- perhaps even to limit our own output -- for the benefit of the land and each other."

Offenburger described "Bet the Farm" as "Simply the best book on agriculture and food production that I've ever read." With such accolades, "Bet the Farm" has been well received in Iowa where Hoffman is attending more events at rural book clubs, stores and local libraries.

"It's been super rewarding hearing from older folks who grew up on the farm and hearing their feedback," she said. "People feel I actually did a good job representing them, and that feels like a success."

More details about John Hogeland and Beth Hoffman's farm, Whippoorwill Creek Farm, can be found on their website, www.iowa-farm.com.

"Bet the Farm: The Dollars and Sense of Growing Food in America," can be found at multiple stores and book-buying websites, including https://islandpress.org/….

Watch a DTN video interview with Beth Hoffman here: https://www.dtnpf.com/….

Chris Clayton can be reached at Chris.Clayton@dtn.com

(c) Copyright 2022 DTN, LLC. All rights reserved.