Sorghum Loses Ground in Texas

Even Before China's Sorghum Tariff, Texas Farmers Were Switching Acres to Cotton, Corn

HUBBARD, Texas (DTN) -- Josh Birdwell serves on the Texas Sorghum Producers Board of Directors, but the 37-year-old Texas farmer had a hard time coming up with a rationale for planting sorghum this spring. And that was even before Chinese tariffs rippled through the planting season earlier this month.

"The last five or six years, we've had some pretty good licks on corn," said Birdwell, who farms about 35 miles northeast of Waco. "Corn has become the big thing around here."

Sorghum took a significant hit April 17 when China announced a 178.6% antidumping tariff on U.S. sorghum. The tariff likely nullified any sorghum exports to China, as evidenced by reports from Reuters last week that at least four ships carrying large sorghum tonnage from the U.S. diverted to new destinations in Japan, Saudi Arabia and Las Palmas in the Canary Islands.

It's too early to project the total impact on the 2018-19 crop, but China has been the dominant user of U.S. sorghum in recent years. In the 2015-16 crop year, the U.S. exported 244 million bushels of sorghum to China, accounting for 74% of China's total imports of the crop. The volume scaled down in 2016-17 to 188 mb from the U.S., but that amounted to 92% of China's sorghum imports that marketing year. USDA's Foreign Agricultural Service projected China would import 248 mb in 2017-18 because domestic production was considered to be in poorer quality.

Based on recent history, that should have translated to somewhere from 185 mb to 223 mb of demand for U.S. sorghum, or roughly half of the total U.S. supply. USDA's World Agricultural Supply and Demand Estimates for April, which came out a week before the Chinese tariffs were announced, pegged U.S. sorghum exports for the 2017-18 crop year at 245 mb.

But in parts of Texas, corn and cotton acres are up at the expense of wheat and sorghum -- or milo as farmers are prone to call it. At 1.6 million projected sorghum acres planted this spring in Texas, sorghum acreage is down about 300,000 in the state from 2016 and is roughly 1 million acres under 2015. A nasty year of sugarcane aphids in 2015 was one of the reasons sorghum acres have dialed back.

"Milo has become pretty much non-existent around here," Birdwell said. "The aphids have been running a lot of guys off."

Texas milo acres are down even though USDA's Prospective Plantings report at the end of March pegged a 5% increase in sorghum acreage nationally to 5.9 million acres. Kansas was projected to grow 150,000 more acres, but Texas was projected to decline by 50,000 acres.

P[L1] D[0x0] M[300x250] OOP[F] ADUNIT[] T[]

Beyond aphids, Birdwell said, corn production has accelerated, at least on his farm, which he attributed to improved genetics that have made corn more attractive to farmers than sorghum. In Hillsboro County where Birdwell farms, he estimates there might be 3,000 acres of sorghum planted.

"The genetics haven't kept up to what the corn has done," Birdwell said. "We have gotten to the point that corn will beat sorghum year after year. These new hybrids on corn have turned the tables quite a bit."

Farther west in the Texas Panhandle, sorghum production is down more than 50% over the past five years, while wheat is also down 20%. Cotton has picked up the slack with better prices, and cotton acres are up 120%, said DeDe Jones, a risk-management specialist with Texas A&M in Amarillo.

Cotton acres are expected to jump about 400,000 acres across Texas this year, according to USDA.

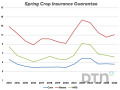

There's a difference in profitability currently between sorghum and other crops such as corn and cotton. But sorghum is less risky from a dryland standpoint. Inputs for dryland sorghum, for instance, might be less than half of what they are for cotton, Jones said.

"We're in a significant drought in the Texas Panhandle, and if you are planting a dryland crop and you don't know how it is going to yield, you can put $150 an acre into a dryland crop like sorghum or $350 into cotton, then to me sorghum is a crop they should at least consider," Jones said.

Shane McLellan, a county Extension agent in Waco, said the price for grain sorghum has waned since China's peak imports of U.S. sorghum. Aphids were only bad one year in the area, but it made farmers leery of the potential increase in chemical costs to ward off the aphids.

"We have a small number of sorghum acres in this county mainly because prices aren't that good," McLellan said. "That's the main driver and there's just not that much profit. When China was pushing for cotton and then grain sorghum, that bumped the price up. When they backed off, then the demand for grain sorghum also backed off."

While at least some farmers have vented about the trade disputes, Birdwell said he's not as worried on the broad scale. He noted that, on a trade trip he took to China, price was the driving factor for Chinese buyers. Birdwell said he believes the Chinese will have to remain reliant on the U.S., especially for soybeans. Birdwell voted for President Donald Trump, and Birdwell said he believes it's important, on a larger scale, to push back on some of China's trade practices.

"Politics is just a lot different from what we do out here every day," Birdwell said. "People are either big-time for him or big-time against him. I feel like it will all work out. I really do."

Birdwell farms about 6,700 acres, 3,500 acres of which went to corn this year. He increased cotton acres, but has about 700 acres of sorghum, mainly because a local feed mill kept calling him this past year looking for sorghum.

"I figured I could put milo in a bin or two and trickle it out a bit," Birdwell said. "Rotation is a good thing for us and having more options is good but, economically, it just doesn't make sense to go with more milo right now."

Birdwell did note that the local wild hog population isn't as bad about tearing up milo fields as they are going after corn. The wild hogs are bad enough in the area that they can actually force farmers to revisit their planting decisions. "That's something that has to be thought about when you are around here," Birdwell said. "Hogs will tear up a new (planted) field, and they go back in after the ears are made."

Chris Clayton can be reached at Chris.Clayton@dtn.com

Follow him on Twitter @ChrisClaytonDTN

(AG/ES)

Copyright 2018 DTN/The Progressive Farmer. All rights reserved.