Kub's Den

Strong Dollar Sets Foreign Grain Buyers' Struggle

A stronger dollar isn't necessarily a bad thing. Agricultural producers can use the stronger dollars they earn domestically to buy international inputs (chemicals from Asia or tractors manufactured in Europe) at "bargain" prices. Okay, not really bargain prices these days, but better than they'd be under other circumstances.

However, for anyone whose pockets aren't filled with American dollars, the surge in the U.S. Dollar Index -- up 20 points over the past 12 months -- is bad news. For instance, it still takes $7 to buy a bushel of corn from an American farmer, but now it takes more units of their own currency -- yen, pesos, quetzals or renminbi -- to buy each dollar.

For a specific example, I looked to soybean purchases from South Korea, which was the second-largest customer in last week's export sales report. While the value of the U.S. dollar has been surging, the price of the South Korean won, in dollar terms, has diminished by more than 20% over the past 12 months. In October 2021 it took 1,175 won to purchase one U.S. dollar. Now in October 2022, someone would have to count out 1,427 won to get the same dollar.

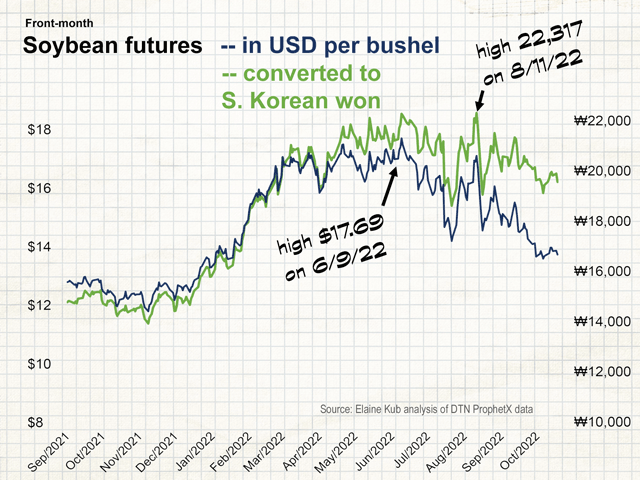

So, while the price on the continuous front-month soybean futures chart in Chicago has fallen $4 per bushel since its June 9 high (22.8% in U.S. dollar terms), the price tag for a bushel of soybeans to be purchased today by a South Korean importer paying in won instead of dollars remains within 12% of its all-time high. On Aug. 11, when you could convert 1,305 Korean won into 1 U.S. dollar, a $17.09 bushel of soybeans was worth 22,317 won. Today, even though a bushel of soybeans has gotten cheaper inside the U.S., it takes so many more won to buy a dollar -- 1,426 won buys 1 U.S. dollar -- that $13.72 bushel of soybeans still takes 19,572 won to buy.

P[L1] D[0x0] M[300x250] OOP[F] ADUNIT[] T[]

When currency valuations remain relatively stable, commodity purchasing power and behavior between one country and the next all makes sense from looking at the futures chart alone. But when gaps start to open between a commodity's value in dollar terms and in yen/peso/quetzal/renminbi terms, foreign customers may be trading a market that looks entirely different on a chart. If the dollar continues higher (which, assuming further interest rate rises, it probably will), it could be the case that, here in the U.S., we never see the north side of $16 soybeans ever again, and yet, our foreign customers will be faced with an unending series of eye-watering, fresh record-high prices. That is, if they don't just wait to buy South American beans instead.

There was no particular reason to focus only on South Korea. We could just as easily have done the same exercise with Chinese yuan (down 11% over the past 12 months), or Portuguese euros (down 15% in dollar terms), or Thai baht (down 15%), or Pakistani rupees (down 27%), or any of our grain or fiber trading partners' currencies. When the dollar goes up, virtually every other currency goes down, because when global trade is effectively denominated in U.S. dollars, it always takes more of the "other" currency to buy each stronger dollar.

Again, a stronger dollar isn't necessarily a bad thing for us in the U.S., but it's a bit of a problem for agricultural producers, because these foreign buyers are our customers and our customers' customers. We know that raising price tags on our products makes them relatively less affordable for a grocery shopper in Cairo, Manila or Panama City. When those price tags are rising beyond our control for some vague, amorphous reason, other than actual scarcity, we know there are likely to be unfortunate consequences. If nothing else, it limits a chart's ability to go up. The global market may need grain prices to fall in U.S. dollar terms, just to keep the final product affordable to people buying in currencies other than dollars. All of this acts on the markets independently of how actual supply and demand might otherwise motivate the charts to move. Overall, it keeps a lid on bullishness.

Fortune magazine recently highlighted how the strong dollar not only makes things a little more expensive for our biggest trading partners, but actually cuts worldwide food consumption. Cargoes are left stranded at ports where countries don't have enough U.S. dollars to pay for the stuff. (https://fortune.com/…) The World Food Program has predicted the largest food crisis in modern history, and traders expect global trading volumes to fall overall when developing countries can't pay for food and feed grains.

A stronger dollar isn't necessarily a bad thing, here, but it's drastically limiting our grain markets' ability to reach some customers on their own terms.

**

Comments above are for educational purposes only and are not meant as specific trade recommendations. The buying and selling of grain or grain futures or options involve substantial risk and are not suitable for everyone.

**

Comments above are for educational purposes only and are not meant as specific trade recommendations. The buying and selling of grain or grain futures or options involve substantial risk and are not suitable for everyone.

Elaine Kub, CFA is the author of "Mastering the Grain Markets: How Profits Are Really Made" and can be reached at masteringthegrainmarkets@gmail.com or on Twitter @elainekub.

(c) Copyright 2022 DTN, LLC. All rights reserved.