Northern Plains Drought Worsens

Deepening Drought in the Northern Plains Takes Toll on Crops, Farmers

ROCKVILLE, Md. (DTN) -- Tyler Stafslien counts the time since his last measurable rain in months, not weeks.

"The last real rain I got on my farm was in August 2020," the Makoti, North Dakota, farmer told DTN. "Spotty rains since then have given us about an inch between now and then. It's the worst dry conditions I've ever seen."

Stafslien's fields in north-central North Dakota are in the epicenter of a devastating drought in the Northern Plains, a drought a full year in the making, which is roasting away the yield potential of one of the most diverse crop areas in the country, farmers and agronomists told DTN.

"These are probably the worst crop stands that we've ever had and the least amount of moisture since probably 1988," said Jason Hanson, an independent crop consultant based in Webster, North Dakota. "When you go into a field and look back at the rows perpendicularly, you see how big the gaps are, for every crop," he said. "Canola, wheat, barley, corn, soybeans, edible beans, field peas, fava beans -- it's all the same."

The drought comes at a particularly painful time for Northern Plains farmers, marketwise. Many finally sold off the last of their stored grain to capture small market rallies last year. Now, with crop prices high once again, many are holding off on selling their future crop, doubtful they can produce enough to fill contracts at harvest, Hanson said.

Drought conditions in the northern U.S. currently spread from the Great Lakes through Minnesota and then worsen dramatically in the Dakotas and into eastern Montana.

"Drought started to grow in late May of 2020," explained DTN Ag Meteorologist John Baranick. "And while it has waffled in and out of drought conditions and severities since then, it has grown to where it is today.

"Drought right now encompasses almost all of North Dakota, northeastern Montana, and far northern South Dakota in D3 -- Extreme Drought -- and there is a good section of north-central North Dakota in D4 -- Exceptional Drought, the highest category for drought," Baranick said.

On June 7, USDA pegged North Dakota topsoil moisture levels at 84% short to very short, and only 14% adequate. In South Dakota, topsoil moisture levels sank to 78% short to very short, with only 22% adequate.

CROPS AND HOPES FADE AS THE HEAT RISES

As each week comes and goes without significant moisture, the crops in the Dakotas have slipped into gradually worse conditions. A recent heat wave which seared the Northern Plains last week didn't help. Most recently, USDA estimated that a third of the North Dakota spring wheat crop and nearly half of the winter wheat crop was in either poor or very poor condition this week.

Some farmers in North Dakota are making the hard decision to walk away from their wheat crop, Hanson said. Previous plans to destroy thin wheat stands and plant other crops, such as corn and soybeans, have mostly been abandoned, for the simple reason that no moisture exists to start up a second crop, he added.

P[L1] D[0x0] M[300x250] OOP[F] ADUNIT[] T[]

"I know one guy who already put his cows out on his wheat," Stafslien said. "I've heard of some wheat being released (by insurers) already, too."

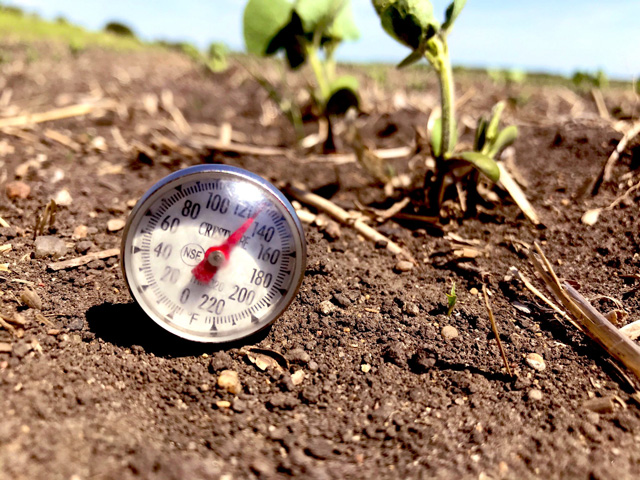

Stafslien planted his wheat at the end of April. "We seeded into dry, hard dirt, hoping the seed would lay until it rained, but the rain has never come," he said. Like many growers around, with good wheat prices in sight, he put in his typical fertilizer inputs. Now he's preparing to abandon some of those thin, spotty stands, which won't take much effort. "I don't even need to spray herbicide to kill it," he said. "That's how bad it is."

As for his soybeans, most of which have yet to emerge a month after planting, he'll treat them like summer fallow acres -- he'll spray to control the weeds, but not another cent goes into the crop, because he won't get it back in yield. "With the price of soybeans what they are, I just hope I can pull in 15 to 20 bushels per acre on average," he said.

That's where Hanson is increasingly leaning on his recommendations to North Dakota farmers, too. "A lot of guys have just given up and the recommendations are changing daily," he said. "I'm not recommending any fungicide -- there's no point to it. If there is not a crop going to happen here, we'll control what weeds we can and try not to spend more money."

Crop stands emerged more fully and are still fighting in some places in North Dakota, mainly low areas and regions that caught spotty rains this spring, Hanson said.

The majority of corn and soybeans in North Dakota were still ranked in fair to good condition as of June 7 by USDA, but they will move south quickly without rain, farmers noted. Many emerged soybean fields took a hit from a late May freeze, and emerged corn stands are now showing severe stress -- pineapple leaves, yellowing from nitrogen deficiency and wilting from the heat wave that hit the Northern Plains starting last week, when temperatures soared above 100 degrees Fahrenheit, Hanson said.

This past weekend, after one particularly brutal Sunday, with 55-mph winds following a roasting hot Saturday, Hanson took a discouraging tour of his region. "It looked like you took a blowtorch and fried the corn leaves, burnt the soybean leaves, sent barley laying flat to the ground, and wheat looks dead," he said.

Root digs showed powdery dry soil, and Hanson suspects most of the spring-applied nitrogen is volatilized and gone. "I don't know what this crop is living on right now," he said.

KEY CROP DEVELOPMENT STAGES AT RISK

The deepening drought comes at a key yield-setting time for grain crops such as spring wheat and corn, said Trace Meyer, a sales and field agronomist with Agtegra, where he covers south-central South Dakota.

There, planting went well and stands emerged beautifully in the spring. But as the rains have dried up, the crops are starting to run out of steam, Meyer noted. "Anything that was turned over or tilled is stressing the worst," he said.

In his region, wheat is starting to flower, a seven- to 10-day stage that does not coincide well with high heat. "My biggest concern is that we'll have to deal with a lot of (sterile) florets and not many seeds per head," Meyer said. "A lot of them will just be left empty."

Cornfields are entering the critical growth stage of V5 to V8. "We're starting to determine how many kernels around each ear will have," Meyer explained. Soybeans are more flexible; they can wait for rain, but their size is being limited, he added. "They're not pushing out any more trifoliates -- they're in a standstill, so they are short and stunted right now."

Most crops in South Dakota could hang on and still yield okay if a rain comes in the next week or two, Meyer said. "But at some point, it will get too late," he warned.

Unfortunately, the outlook for moisture for the rest of the summer is not promising, according to DTN's meteorology team.

DTN's long-range outlook has less confidence than normal, thanks to a neutral phase of El Nino forcing meteorologists to rely on seasonal weather influences that are harder to predict more than a couple weeks out, Baranick noted. But forecasters can lean on "analog years" for guidance, where similar conditions, such as the neutral El Nino, occurred. One such year that has surfaced as an analog is 2012, when drought baked large swaths of the Midwest in late summer.

"The long-term outlook does not look favorable for growing row crops in the Northern Plains," Baranick concluded.

"Already starting at a disadvantage with the extreme to exceptional drought early in the growing season, models indicate good chances for below-normal precipitation through the rest of the summer," he said.

"That does not mean that it will be completely dry, but the region will need to count on timely rainfalls to produce decent yields rather than abundant precipitation to reverse the drought," Baranick added. "But if you add on the above-normal temperature forecast, dryness and heat should increase drought throughout the region."

That confirms the growing feeling in North Dakota that history will be made this year, Hanson said.

"I was 20 years old when 1988 hit," he said, referencing that year's historic drought. "Those were pretty brutal years, but that was back when input costs were lower -- you could survive on 40-bushel wheat. Right now, I think my best wheat will be 40 bushels per acre, and the vast majority will be closer to 20 bushels -- if we get rain."

See more on the drought's effect on the Northern Plains' spring wheat crop from DTN here: https://www.dtnpf.com/….

See more from DTN's weather team on the drought in the Northern Plains here: https://www.dtnpf.com/… and here: https://www.dtnpf.com/….

Emily Unglesbee can be reached at Emily.unglesbee@dtn.com

Follow her on Twitter @Emily_Unglesbee

(c) Copyright 2021 DTN, LLC. All rights reserved.