ESA Saga of the Lesser Prairie Chicken

Cattle Groups Fight Addition of Lesser Prairie Chicken to Endangered Species List

OMAHA (DTN) -- For the second time in the past nine years, the lesser prairie chicken will officially be added to the Endangered Species list Monday, though Plains states, livestock groups and oil drillers have already asked a federal court in Texas to rescind the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service designation.

If the bird's listing under the Endangered Species Act (ESA) holds, the Fish and Wildlife Service rule will require livestock producers in parts of five states to create grazing plans mainly to protect themselves from any activities that could harm the birds. Landowners will face more complications trying to take acreage out of the Conservation Reserve Program (CRP), especially if they want to put the land back into crop production.

For landowners and livestock producers who are enrolled in a USDA Natural Resources Conservation Service program, NRCS is working with the Fish and Wildlife Service to ensure NRCS conservation plans also meet the grazing plan requirement.

"We're working very closely with landowners on conservation plans, and they are implementing those practices that we're recommending. They are going to have that assurance and that certainty that they can continue to do that work," said Terry Cosby, chief of USDA's NRCS.

For now, the ESA listing of the lesser prairie chicken faces a new barrage of litigation. On Wednesday, Texas Attorney General Ken Paxton filed a lawsuit against the Department of Interior and U.S. Fish in Wildlife in the U.S. District Court for the Western District of Texas -- the same court that in 2015 threw out the last ESA listing for the lesser prairie chicken in 2015. Along with the Texas AG's lawsuit, a companion lawsuit was filed Wednesday by the Permian Basin Petroleum Association, the National Cattlemen's Beef Association, and cattlemen's groups from Kansas, New Mexico, Oklahoma and Texas also in the same federal court.

The attorneys general for Kansas and Oklahoma also have threatened to sue. County governments across the five states also have passed resolutions to join the litigation.

4(d) GRAZING PLANS

For livestock producers, the controversy around the listing comes from what is known as the "4(d) grazing plan," which is an ESA regulatory compliance plan. The grazing plan mechanism was basically set up to recognize that livestock grazing and rangeland are both critically important for the lesser prairie chicken habitat, but the act of grazing itself could lead to incidental killing of birds, such as destruction of nests -- dubbed a "take" in FWS terminology.

"So, we're not trying to set the bar for livestock operations in terms of how they operate," said Chris O'Melia, a wildlife biologist with the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service who spoke by livestream at a conservation conference in Manhattan, Kansas, in early February. He added, "So there is some potential for take that occurs in grazing activities. It's fairly limited, and the benefit to the species that we can accept that take is there is a grazing place."

In their lawsuit, the livestock groups challenge the validity of the grazing plans. They point out that FWS considers cattle grazing as "essential to managing and maintaining healthy grasslands and shrublands" because it provides habitat for the lesser prairie chicken. At the same time, FWS sees cattle grazing as a risk for incidental destruction of lesser prairie chicken nests as well.

In their lawsuits, both the state of Texas and the cattle groups also make the case that the grazing rule essentially outsources Endangered Species Act enforcement and grazing management to unidentified third parties, which goes beyond the Fish and Wildlife Service's authority under the ESA.

"The ESA does not grant the Service (FWS) the power to delegate enforcement of the ESA to unspecified third parties," the livestock groups state in their complaint.

HABITAT DECLINE

In its listing of the bird, FWS cited the main requirement for lesser prairie chicken populations is "large, intact, ecologically diverse grasslands." The biggest threats to the lesser prairie chicken include conversion of grassland to crop production; petroleum and natural gas production; wind energy development and power lines; and woody vegetation encroachment; as well as roads and other factors such as livestock grazing.

FWS estimates that the lesser prairie chicken's range has seen more than 4.9 million acres lost as landowners have converted grasslands to crop production.

P[L1] D[0x0] M[300x250] OOP[F] ADUNIT[] T[]

Drew Ricketts, a wildlife specialist at Kansas State University, said on a KSU Extension video that lesser prairie chickens like a lot of short grass for mating season, a lot of dense cover for nesting, and they don't like any trees where predators can eyeball them.

"Areas with zero trees per acre are 40 times more likely to be used (by lesser prairie chickens) than areas with five trees," Ricketts said.

While cultivated farm ground is already considered non-habitat, Ricketts indicated landowners who are looking at land conversions need to be assured they either don't have lesser prairie chickens or any project on their land is far enough away from a population of birds.

"Are there chickens there or not? If you know there are lesser prairie chickens on your land or your neighbor's land, then you need to be careful," Ricketts said.

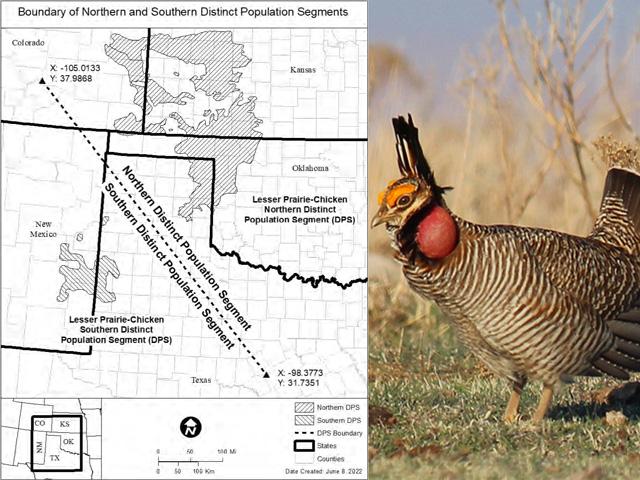

NORTHERN-SOUTHERN SPLIT

For the first time, the Fish and Wildlife Service splits the lesser prairie chicken into two distinct populations. The southern population of lesser prairie chickens will be considered as endangered in parts of western Texas and eastern New Mexico.

The bird would be listed as "threatened" in a larger territory that includes eastern Colorado, western Kansas, western Oklahoma and a few counties in the Texas Panhandle.

The oil and livestock groups, in their lawsuit, call the splitting of lesser prairie chicken into two separate populations as "a divide-and-conquer approach." Texas officials cited that the FWS doesn't explain the reasons for creating the northern-southern populations.

LEKKING SEASON STARTS

The ESA listing also comes at the start of mating season, when more people are venturing out to areas such as western Kansas just to watch the birds' mating rituals.

This weekend, Jim Millensifer starts guided viewing and photography sessions on three western Kansas ranches as lesser prairie chicken mating season begins when male prairie chickens make booming noises, strut and show off their feathers. The morning rituals are dubbed as "leks." Millensifer will take groups out to see leks nearly every weekend for the next two months. He's hosted more than 700 guests from 36 states and 18 countries since he started the guided tours in 2018. The Kansas Audubon Society will also host some tours in April.

"It's a huge deal for birders," Millensifer said. "If they want to see them or photograph them, this is really the only place you can do it."

While his lek viewings are growing in popularity, Millensifer said he expects there will be a decline in the number of lesser prairie chickens his bird watchers see this year. Drought and heat over the past couple of years have hammered the bird's nesting and breeding activities.

Over the longer term, Millensifer also pointed out, the development of wind energy, natural gas and oil exploration, along with the decline in Conservation Reserve Program (CRP) acreage have all combined to reduce habitat for the lesser prairie chickens.

"The listing is definitely warranted, and this is just my personal opinion, and the listing is needed, but I don't know if it's too little too late," he said.

While not a farmer or rancher, Millensifer said the landowners he works with have sought to enhance lesser prairie chicken habitat on their lands, particularly with rotational grazing and not overgrazing their ground.

"All of their activities have helped them become more successful and profitable in ranching but also have significantly benefited the habitat, and that's why they have chickens on their property, but also all of the short-grass prairie wildlife," Millensifer said. "It's also helped them to be more profitable as ranchers."

LONG-STANDING BATTLE

The battle over the lesser prairie chicken listing goes back to 1995 when the Center for Biological Diversity and other groups first petitioned the Fish and Wildlife Service to protect the bird.

In 1998, FWS put the lesser prairie chicken on a "candidate species" list.

The Center for Biological Diversity continued to press the issue, leading to a 2011 settlement requiring FWS to make determinations over hundreds of animals. That prompted FWS to first propose listing the lesser prairie chicken as a "threatened" species in 2012.

FWS went ahead in April 2014, declaring the lesser prairie chicken as a threatened species, which prompted lawsuits in Oklahoma and Texas. In September 2015, the U.S. District Court for Western Texas threw out the FWS decision, stating the agency didn't adequately consider the impact of voluntary and state conservation efforts to evaluate if lesser prairie chickens will decline or increase in population in the future.

Texas officials make the same argument in their new lawsuit, pointing to a $10 million Southern Plains Grasslands program that "will likely result in some future benefits for the lesser prairie chicken. The Texas AG cited FWS doesn't make any projections about the possible benefits of that grassland program."

In September 2016, the Center for Biological Diversity, Defenders of Wildlife and WildEarth Guardians again came back at FWS with a petition, arguing a listing was needed to avoid a "dire risk of extinction" for the birds. That petition also proposed breaking up the FWS listing into three different "Distinct Population Segments."

In 2019, the environmental groups sued the Department of the Interior, alleging that FWS failed to make a listing decision on the lesser prairie chicken. The settlement in that case led to the proposed listing.

Environmental groups again came back in August 2022, citing that if FWS did not move to protect the lesser prairie chickens within 60 days, they would sue. The Department of the Interior filed its listing in mid-November.

U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service 4(d) Rule: https://www.fws.gov/…

KSU Extension interview on lesser prairie chicken: https://www.youtube.com/…

Chris Clayton can be reached at Chris.Clayton@dtn.com

Follow him on Twitter @ChrisClaytonDTN

(c) Copyright 2023 DTN, LLC. All rights reserved.