Revisiting the 1980s Farm Crisis

In New Book, Former North Dakota Ag Commissioner Spotlights Fight to Save Family Farms

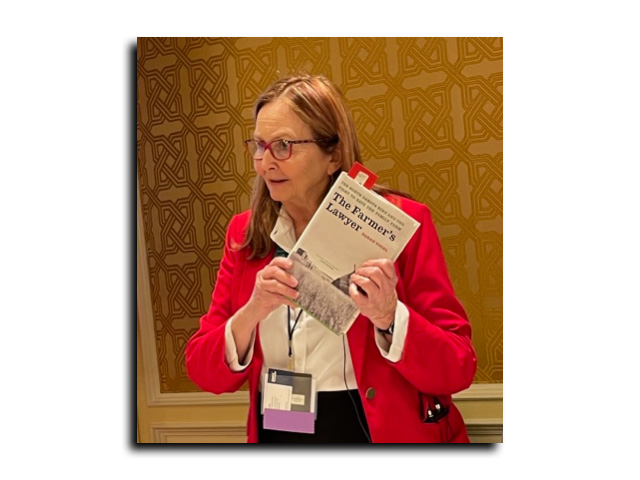

WASHINGTON (DTN) -- Sarah Vogel, the former North Dakota agriculture commissioner who famously won a class-action suit against the Agriculture Department's attempts in the 1980s to foreclose on the farmers it was supposed to help, has written a memoir of that struggle, "The Farmer's Lawyer: The North Dakota Nine and the Fight to Save the Family Farm."

Bloomsbury Press released the book on Nov. 2, and it is available in bookstores and online.

In recent weeks, Vogel has spoken about the book at the annual meeting of the American Agricultural Law Association in Salt Lake City and at events in North Dakota and Minnesota.

In a speech, Vogel told the lawyers she hoped the story of her victory for 240,000 farmers in one class-action suit would show them "the importance of lawyers working with farmers." And she has said at events in Minnesota and North Dakota "there needs to be a big upswell" in support for family farmers through stricter antitrust efforts and aid to young and beginning farmers.

"The Farmer's Lawyer" is an extraordinary mix of a landmark legal case and the personal story of a young single mother who was so determined to use her legal skills to help the farmers that she lost her house and was so stressed she failed at attempts to give up smoking while the case was ongoing. The results of the case can still be seen today in the Agricultural Credit Act of 1987 and reforms to the way the Agriculture Department handles the appeals of farmers who borrow money through USDA and run into trouble.

The backdrop of the case is the farm situation of the 1980s. In the 1970s, the Soviet Union and Middle Eastern countries imported a lot of grain, prices skyrocketed, and market-related farm subsidy payments weren't activated. Earl Butz, the Agriculture secretary in the Nixon administration, urged farmers to "plant fencerow to fencerow." Farmers did plant more acreage, sometimes on land that should never have been farmed, and they bought land at rising prices.

But by the late 1970s, the Federal Reserve raised interest rates in an attempt to curb inflation. Exports declined, President Jimmy Carter halted grain sales to the Soviet Union over the invasion of Afghanistan, and grain was stockpiled. The farmers who had borrowed money from the Farmers Home Administration (FmHA), an agency set up during the New Deal to help the more marginal farmers, had trouble paying off their loans. After President Ronald Reagan's election, David Stockman, director of the Office of the Management and Budget, directed the Agriculture Department to reduce delinquent loans.

P[L1] D[0x0] M[300x250] OOP[F] ADUNIT[] T[]

As USDA was threatening to foreclose on the farmers to which it had lent money, enter Sarah Vogel, a North Dakotan who had gone to law school at New York University and had worked for the New York City Department of Consumer Affairs, the Federal Trade Commission and, ultimately, as a political appointee on consumer affairs at the Treasury Department in the Carter administration. Vogel, who after Carter's defeat had moved back to North Dakota to start a law practice and raise her son, immediately started getting calls from farmers in trouble with FmHA.

After 14 years on the East Coast, the granddaughter of the manager of the state-owned Bank of North Dakota in the 1930s and the daughter of a lawyer who was a North Dakota Supreme Court justice was pulled back into rural life. She had been raised in the tradition of the Nonpartisan League, a leftist political party that defended Midwestern farmers in the early 1900s.

"I was a Vogel, and I had to protect farmers," she said during a recent reading at a bookstore in Fargo, North Dakota.

With her NYU legal education and Washington experience, Vogel initially thought that if she explained to FmHA bureaucrats that they were not following their mission to help farmers, they would back down from what she calls their "starve-outs and foreclosures." But she underestimated the Reagan administration's determination to get delinquent loans off USDA books. More and more farmers all over the country got into trouble. Life magazine sent a reporter to North Dakota to write about what was becoming known as the farm crisis. The Life article, published in November 1982, focused on Vogel. After that, her phone rang off the hook.

Eventually, she got help from other lawyers around the country and decided she had the makings of a class-action case. Most of the book is devoted to the stories of the troubled farmers and the legal strategies behind the case. But that story is leavened with Vogel's personal tale and commitment. She lost her house and was forced to work for her father's law firm and bring her son to live for a time in her parents' basement. But every time the farmers' situation looked hopeless, something positive happened. Finally, in 1984, Federal Judge Bruce Van Sickle issued a permanent injunction stopping the foreclosures on the 240,000 farmers.

In his ruling on Coleman v. Block, Van Sickle said FmHA had been set up "to help farmers retain their land despite droughts and depression," but the agency had become "a far-flung undertaking by the United States government to bolster the credit position of practically all farm operations, farm-related businesses and rural towns and communities." The Reagan administration, he said, had abandoned FmHA's principles in a zealous mission to reduce delinquencies. The judge also issued directives to FmHA to remedy the situation.

Vogel went on to serve two terms as North Dakota's agriculture commissioner, the first woman elected to that position in the country. Later, in private practice, she was one of the lawyers in the successful Keepseagle class-action suit that found USDA had discriminated against American Indian farmers by not providing proper services.

Vogel's memoir has won praise from both Willie Nelson, the entertainer who started Farm Aid, and from lawyer-writer John Grisham.

"Sarah Vogel and I share an ornery persistence in the face of bullies," Nelson said. "This is her real-life story of fighting for farmers as they were pushed off the land by a plan, ordered and carried out by top officials of our government. Sarah's story, told in her unique voice, inspires me -- and I'm sure it will inspire you -- to fight for family farmers."

Grisham said, "This is my kind of story -- the young, inexperienced lawyer facing big odds. It's remarkably well told and heartfelt. I really enjoyed it."

Vogel has turned from practicing law to writing. She recently wrote an essay on F. Scott Fitzgerald's character Jay Gatsby, whom she describes as "the most famous North Dakotan" even though many people have overlooked that.

"The Farmer's Lawyer" is a tale of legal and personal struggle, but it also shows the determination -- indeed, the obsession -- that is needed to change the world, or as Sarah Vogel told her father, "We've gone and made some law."

"The Farmer's Lawyer" can be found at https://sarahmvogel.com/…

Jerry Hagstrom can be reached at jhagstrom@nationaljournal.com

Follow him on Twitter @hagstromreport

(c) Copyright 2021 DTN, LLC. All rights reserved.