South America Calling

El Nino Likely to Bring Good Weather for South American Crops

It was three straight growing seasons of La Nina-controlled weather in South America, which produced a wide range of weather issues for Argentina and Brazil. 2020-21 was characterized by a delayed start to the wet season and planting in Brazil, followed by significant and widespread frosts for the safrinha corn crops.

The 2021-2022 campaign went better, but we still saw abnormally dry conditions in southern Brazil and Argentina pare back the potential. The 2022-23 season saw a record soybean and corn crop in Brazil, though harvest is still ongoing in southern Brazil because of significant delays in the safrinha (second-season) corn planting. And Argentina had one of its worst droughts in the last century dry up its crops and put it in rough shape for the coming 2023-24 season.

This season will be very different, though. El Nino has developed in the tropical Pacific Ocean, and that phenomenon is usually a good one for South American farmers. El Nino is characterized by above-normal sea-surface temperatures in the tropical Pacific Ocean and changes the weather patterns world-wide. On average, the effects of El Nino are the exact opposite from La Nina for South America.

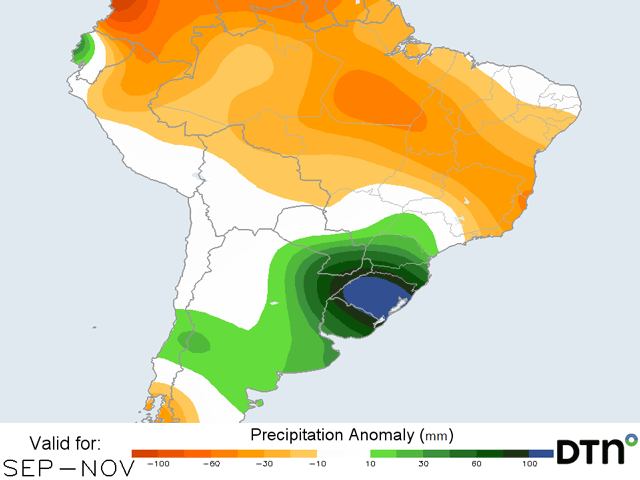

During the growing season, northern Brazil usually sees below-normal rainfall, which can bleed into portions of central Brazil as well. Also, temperatures are usually higher. But the weather pattern across Argentina and southern Brazil is more active, and rainfall amounts trend above normal for the spring and summer.

CENTRAL BRAZIL SEES MIXED CONDITIONS

Central Brazil relies on a timely start to its wet season, when showers and thunderstorms develop nearly every day, to produce a double crop of soybeans followed by corn or sometimes cotton. The beginning usually occurs in late September and lasts through early May.

The seven-month-long period of consistent and heavy rainfall, on the order of 8 to 12 inches of rain per month during the peak, allows for a full soybean crop to be harvested in late January and February, followed by a corn crop that can get to and through pollination before the rains shut down. The crop then relies upon ample subsoil moisture to fill out the kernels and finish out the season.

P[L1] D[0x0] M[300x250] OOP[F] ADUNIT[] T[]

During La Ninas, the wet season is usually retracted. That was certainly the case in the 2020-21 season on both ends. Faster ends to the wet season were noted in both 2022 and 2023, and pared back some of the potential on eventual record corn crops.

The switch to El Nino has little impact on the wet season, though may make the showers less frequent and widespread. That could lead to some areas having longer stretches of dry weather, but when the region averages 8 to 12 inches of rain each month, a little bit of a gap usually is not an issue for the soybean crop. However, the lower rainfall can lead to more limited subsoil moisture for the safrinha crop to draw on once the rains end in April or May. But typically, this area only has minor issues due to El Nino.

Central Brazil has already lucked out with some early rainfall. During the last week, a front moved into and stalled in the region, bringing estimates of 25 to 75 millimeters (1 to 3 inches) of rainfall in some lucky locations.

Producers in the region usually wait until 25 to 50 mm (1 or 2 inches) of rain have fallen from wet season showers to begin planting to ensure good seed-to-soil contact and even germination after a long dry season. With that already having occurred across a fairly wide area, planting may begin early, which would increase the window for both the soybean and safrinha corn seasons. Although, with a drier period now until the actual start to the wet season, producers may hold off a bit to ensure the rains indeed come in a timely fashion later this month. This will bear watching.

SOUTHERN BRAZIL AND ARGENTINA WELCOME EL NINO

It is southern Brazil and Argentina that benefit the most from the Pacific Ocean's warmth. An active feed of moisture into frequent storm systems allows near- or above-normal precipitation across both areas from September through January and sometimes deeper into the season as well.

Northern sections double-crop soybeans with corn like central Brazil, but Argentina may only have a single crop or double crop winter wheat and barley with soybeans, corn or sunflowers. The growing season is expanded, but not enough to have a full soybean and corn crop in the same field in the same marketing year.

With the longer growing season, it allows producers to spread their planting risks in two stages for corn. Early planting begins in late September through October while later planting waits until December and into early January. The reason for the gap is that if a dry spell does occur in Argentina, it is typically in January and corn planted in November would pollinate in January, an inopportune time. However, that may not matter this year as the forecast and typical effects of El Nino lead to the likelihood of better rainfall throughout the period.

As El Nino wanes toward the end of Southern Hemisphere fall, the effects on the atmosphere will wane as well as its benefits. Thus, later-planted crops will not enjoy the full benefits that El Nino has to offer. There is less certainty in the outcome for the safrinha crop in Brazil, or later-planted corn and soybeans in Argentina. Still, if the expected above-normal rainfall occurs, that may not matter as the area would have built up plenty of subsoil moisture to float through some drier stretches toward the end of the season.

Argentina is coming off an historic drought. And although the winter has been active in terms of systems moving through, rainfall has been sparse. Drought still exists for much of the western half of the country's croplands. Eastern areas have fared better.

However, El Nino's active weather appears to be making a promising turn. A front and system this weekend is forecast to bring widespread and locally heavy rainfall through the country. That looks to be followed by a similar system later next week. Both will help to ease drought conditions and raise expectations for better and more on-time planting when compared with the last couple of years.

Unlike Argentina, the active pattern in southern Brazil has been very fruitful in terms of rainfall over the winter. In fact, it has been difficult for producers to harvest the remaining safrinha corn in some areas due to wetter conditions. Winter wheat areas have been very happy to see the rainfall, however.

The rains that come with the two systems appear to be heavy and amounts over 75 or even 100 mm (3 or 4 inches) appears possible. Rain that heavy would not be favorable for either filling wheat or harvesting the remaining corn if flooding occurs. We may see delays to planting and that could throw off the safrinha corn crop in 2024. But overall, soils are well-primed to allow for planting and good early growth once restrictions are lifted later this month.

To find more international weather conditions and your local forecast from DTN, visit https://www.dtnpf.com/….

John Baranick can be reached at john.baranick@dtn.com

(c) Copyright 2023 DTN, LLC. All rights reserved.