Soaring Soy Oil Demand

The Big Crush

Soybean oil used to be so plentiful decades ago that restaurants, food manufacturers and other industries couldn't use it all. Surplus supplies were viewed as a waste product with little value.

How times have changed. The fortunes of soybean oil have come full circle thanks to a renewable diesel fuel boom that is driving soy oil demand, raising expectations for higher commodity prices for farmers and laying the foundation to potentially transform the soybean industry.

Renewable diesel production and demand is soaring, which could increase the floor for soybean and corn prices by at least $3 and $2 per bushel, respectively, explains DTN Lead Analyst Todd Hultman. He likens the rise of the biofuel and commodity prices to the ethanol boom in the mid-2000s.

"It's a new dimension of demand for soybean products that we've never seen before," Hultman says. "It's hard to grasp the potential."

Growing pains are also expected as the renewable diesel industry expands and secures needed feedstocks, namely soybean oil. It appears soybean oil will overtake soybean meal as the primary driver to crush beans.

Hundreds of millions of bushels of new soybean crush capacity is expected to come online over the next few years. It will likely incite a battle for acres and reshape the soybean complex and trade.

"In reality, at times, it's not going to be as rosy as it all looks on the chalkboard now," Hultman contends.

RENEWABLE DIESEL BOOM

Renewable diesel production capacity has exploded. It nearly doubled from 971 million gallons per year in May 2021 to 1.92 billion gallons in May 2022, according to the U.S. Energy Information Administration (EIA). Refiners are quickly ramping up production to satisfy an insatiable demand for the environmentally friendly, low-carbon fuel and cash in on federal and state tax credits. The federal Renewable Fuel Standard (RFS) also generates a potentially lucrative market for renewable identification numbers, or RINs.

Clean Fuels Alliance America (formerly the National Biodiesel Board) says renewable diesel production capacity could hit 5.5 billion gallons by 2026 if announced refinery expansions occur. That's in addition to 2.2 billion gallons of biodiesel production capacity as of May, according to EIA data.

Donnell Rehagen, CEO of Clean Fuels Alliance, says the RFS generates demand for biofuels, but states with low-carbon fuel standard (LCFS) policies are driving renewable diesel use. California, he says, is the top destination for the fuel.

"California has found electrification of transportation is a little more challenging than they thought ... so they've become very reliant on biomass-based diesel (renewable diesel and biodiesel) to meet their carbon reduction goal of 20% by 2030," Rehagen says. "Since renewable diesel is made similarly to petroleum diesel ... it's literally a drop-in replacement and suitable for high blends. California will take all the renewable diesel that can be sent."

Studies show biodiesel greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions are, on average, 80% below petroleum diesel, according to Clean Fuels. Several state and federal agencies concur with the findings, including the California Air Resources Board.

California currently uses more than 1.2 billion gallons of biodiesel and renewable diesel annually, and consumption is increasing rapidly, Rehagen says. "We expect by 2030, that will be well over 3 billion gallons, which is slightly less than our entire industry's production capacity today."

LCFS policies in other states and Canada will also increase renewable diesel demand, Rehagen claims. He adds that companies such as FedEx and Amazon, with policies to reduce their carbon footprints, may be an even bigger demand driver than government mandates.

"You can't move goods without transportation, and many of those companies have decarbonization goals," Rehagen continues. "I think (renewable diesel demand) will continue to grow."

WANTED: SOYBEAN OIL

Soybean oil has the most growth potential of all biomass-based diesel feedstocks to meet future industry needs, according to a recent study by LCM International, an international ag consulting firm. Other feedstocks include animal fat and grease, used cooking oil, corn and canola oil, and more.

The study, "Lipid Feedstocks Outlook to 2030," commissioned by the Advanced Biofuels Association, projects feedstock consumption for biomass-based biodiesel will increase from 19.8 billion pounds in 2020 to 70.5 billion pounds by 2030. Soybean oil currently accounts for nearly half of the feedstocks used.

"Soybean oil will have to carry it (feedstock demand)," Rehagen says, noting other feedstocks have limited growth potential.

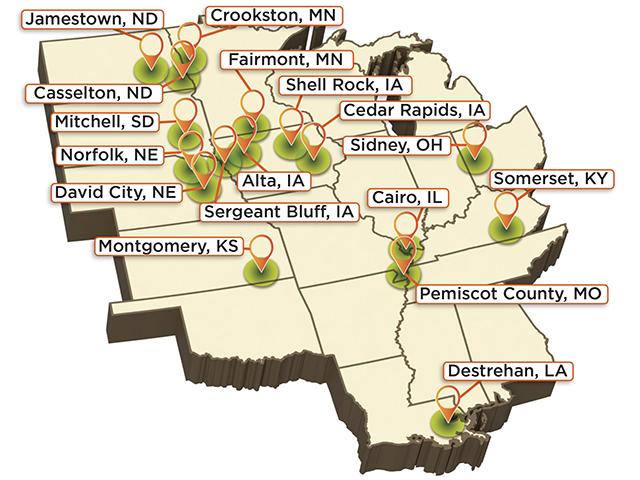

A rapid expansion of U.S. soybean crush capacity is underway to meet future soybean oil demand. At least 17 new soy-processing projects are in various stages of construction, expansion or development, according to recent company announcements.

Altogether, more than 564 million bushels of additional soybean demand is expected in the next few years. (The number is likely tens of millions of bushels low since Cargill and Ag Processing Inc. [AGP] are increasing crush capacity at three existing plants but declined to provide bushel figures to DTN/Progressive Farmer.)

According to the November USDA "World Agricultural Supply and Demand Estimates" report, crush estimate for the 2022-23 marketing year is a little more than 2.2 billion bushels.

"This is significant new demand," says Corey Jorgenson, CEO of Shell Rock Soy Processing. The plant is being built in Shell Rock, Iowa, and is expected to be operational late this year. Crush capacity is 38.5 million bushels annually. "I think it does reset (soybean) prices."

P[L1] D[0x0] M[300x250] OOP[F] ADUNIT[] T[]

COMPETITION SPURS PRICES

Crushers and foreign buyers will battle for whole beans. Biofuel refiners, food companies and other industrial users will vie for soybean oil. As competition heats up, soybean and corn prices are destined to rise with the battle for acres, Hultman explains.

"It's as bullish a change in demand as we've seen since the ethanol boom, and it might be even bigger," he adds. "It's a net positive for farmers overall."

While difficult to predict how average commodity prices will be affected, Hultman says added demand will give prices more support. He "wouldn't be surprised" to see a new floor price for soybeans at roughly $11 per bushel, up from $8 per bushel. For corn, the new support level could easily increase from $3 to up to $5 per bushel.

"Even though commodity prices are high now, and downtimes seem far away, I think it's in the downtimes when the value of biofuels really show up for the farmer," Hultman says.

University of Minnesota Extension released an economic impact and basis analysis report in early 2019 pertaining to Epitome Energy, a new soybean crush plant in Crookston, Minnesota. The plant is securing necessary permits, and construction will commence when that occurs, CEO Dennis Egan tells Progressive Farmer. Annual crush capacity is 42 million bushels.

Soybean basis levels near Crookston are estimated to improve by 10 to 20 cents per bushel, possibly higher in other locations, according to the report. Cash soybean bids at the CHS soybean-processing facility in Fairmont, Minnesota, are routinely 15 to 30 cents per bushel greater than grain elevators within 10 to 30 miles of the town, the report says. CHS recently expanded the plant's crush capacity from 55 to 72 million bushels per year.

Ed Lammers raises soybeans in northeast Nebraska near Hartington. He's looking forward to an economic boon that two new large bidders for soy in the state will bring when crush plants in Norfolk and David City are operational in 2024 and 2025, respectively. The combined crush capacity of the plants is 88.5 million bushels per year. Nebraska produced nearly 351 million bushels of soybeans in 2021, according to USDA data.

Lammers expects competition for bushels will bolster soybean bids within 100 miles of the plants because farmers, like him, aren't afraid to truck soybeans if the price is right.

"My basis will be narrowed. It's a plus for eastern-Nebraska soybean producers and our economy," he surmises.

Illinois farmer Stan Born agrees revenue potential because of more competition for soybeans is exciting, but, "it's always tempered by reality, because there's a lot of hurdles to be able to realize all that excitement."

QUESTIONS PERSIST

Will there be enough soybean acres and production to satisfy growing domestic and foreign demand? Will there be adequate, affordable feedstocks for all renewable diesel and biodiesel plants, both big and small? As crush increases, is there a market for more soybean meal? Can soybeans be bred to produce more oil without sacrificing yield and protein content?

All of these questions are on the mind of John Heisdorffer, who farms near Keota, Iowa. As an investor in Iowa Renewable Energy (IRE), Washington, Iowa, he's most worried about the future of small biodiesel plants like IRE. Its capacity is a little more than 30 million gallons per year.

Heisdorffer calls renewable diesel expansion a double-edged sword. Increased soybean demand and prices are good, but soybean oil and other feedstocks are harder for biodiesel plants to secure and more expensive. That's a burden for small refineries such as IRE.

The average projected price of soybean oil is 69 cents per pound in the 2022-23 marketing year, according to the November USDA "WASDE" report. Soybean oil futures neared a record 90 cents per pound in April, more than triple the price from two years earlier.

Heisdorffer, who's a member of IRE's board of directors, says skyrocketing feedstock costs are making it difficult for the plant to operate in the black. "It's hard for a smaller biodiesel plant to make headway these days, because we don't have the capital to buy soybean oil for a year or make an agreement to buy it for a year."

He's worried about the long-term future of IRE and other small biodiesel refineries as giant petroleum companies jump on the renewable diesel and biodiesel bandwagon, and partner with crushers. Some examples:

-- Chevron recently purchased Renewable Energy Group, the nation's largest biodiesel producer.

-- Chevron invested $600 million to expand two Bunge soybean crush plants for the rights to buy the soy oil to produce renewable diesel and sustainable aviation fuel.

-- Phillips 66 invested in Shell Rock Soy Processing for the rights to buy all of the more than 400 million pounds of crude soybean oil it's projected to produce annually at full capacity. Phillips 66 is converting its Rodeo, California, oil refinery into a biofuel juggernaut capable of making 800 million gallons a year of renewable diesel, renewable gasoline and sustainable aviation fuel.

-- ADM and Marathon Petroleum Corp. are partnering to build a $350-million soybean-processing facility in Spiritwood, North Dakota. When complete in 2023, the facility is expected to produce 600 million pounds of refined soybean oil annually that will produce 75 million gallons of renewable diesel per year.

"We can't get enough feedstocks now to run at full bore," Heisdorffer says, noting more soybean acres will be needed and possibly tweaking breeding programs to change soybean composition. "The next thing, I guess, is pushing the limits of the soybean itself as far as oil content."

SUPPLY CHALLENGES

Mixed opinions and analysis exist about whether soybean acres and feedstocks can be increased enough to allow biomass-based biodiesel production to grow as projected.

As soy acres and yields increase, the LCM International study projects the U.S. won't have an issue producing 70.5 billion pounds of feedstocks needed to meet demand.

In a U.S. Soybean Export Council (USSEC) webinar late last year, LCM founder and ag researcher James Fry says soybean price signals will prompt farmers to plant more. "In the U.S., it will be partly taking land from other crops."

Fry predicts soybean acres will rise to 94 million to 95 million by 2030. Farmers planted 88.3 million acres this year, according to the USDA "Acreage" report released in June.

A Rabobank study, "Soy Oil Fueling Crush Expansion: A Ten-Year Outlook," forecasts a nearly 12-million-acre increase is needed in the short term to cover expanded crush demand for renewable diesel without hurting U.S. soybean exports.

Hultman says that's unlikely, as overall row-crop acres in the U.S. aren't expected to significantly increase. "I think at the end of the day, we're still not going to get very far away from a 50-50 split on corn and soybean acres."

Fry predicts average soybean yields will increase nationwide to 55 bushels per acre (bpa) within the decade, up from 51 bpa in 2020 and 51.4 bpa in 2021, according to USDA data. He also expects seed companies to work harder to edge up the oil content in soybeans.

Chuck Hansen, of Stine Seed, headquartered in Adel, Iowa, says improving yield is always the top priority of the company's breeding program. That's occurring at about 0.8 bpa per breeding generation, he says.

As biofuel demand grows, Hansen knows the drums are beating louder to increase oil content of soybeans without sacrificing protein. Doing so, he says, isn't easy since the two are inversely related, meaning if oil content is increased, protein often goes down and vice versa.

"In our soybean-breeding program, we're analyzing every line that goes into our elite trials, which is the final evaluation before we commercialize a line," Hansen says. "We're specifically identifying lines that will give us higher protein and oil."

RESHAPING SOY EXPORTS

The amount of U.S. soybeans available for export could drop by hundreds of millions of bushels. Is China, the world's largest soybean importer, and other soy importers worried the U.S. will likely have less whole soybeans to sell?

"They are taking notice and asking questions," says Jim Sutter, USSEC CEO. "We think we'll still have a good, solid supply of soybeans to export."

He acknowledges soy oil exports will eventually decline. However, he considers the probable change in export dynamics an opportunity. Crushing is a value-added proposition, and the U.S. will eventually have more soybean meal to sell that many countries in the European Union, Southeast Asia and elsewhere crave.

Sutter foresees:

-- better soybean economics relative to other crops for farmers to attract additional soybean acres.

-- competitive feed costs for livestock producers as soybean meal prices reach levels to ensure demand grows along with supply.

-- U.S. soybean meal exports to double in the next decade depending on future soybean acres and how much crush capacity is actually built.

-- worldwide protein needs to continue to escalate.

Sutter believes a market will be available for all the soybean products produced in the U.S.

"More crush is a good thing," Sutter says. "We've been preparing for this for years by promoting the nutritional benefits of soybean meal produced from U.S. soybeans, such as enhanced amino acid profile and energy levels."

**

DID YOU KNOW:

-- According to the American Soybean Association and Clean Fuels Alliance America, all biodiesel isn't the same. Biodiesel is a mono-alkyl ester of long-chain fatty acids. In simple terms, a fat or oil (soybean oil) is reacted with an alcohol-like methanol in the presence of a catalyst. This process yields biodiesel and crude glycerin. Biodiesel is typically used in blends with petroleum diesel from 2 to 20%. Renewable diesel is a hydrocarbon, which is the same chemical as petroleum-based fuels. It's produced through hydrotreating, a high-temperature and high-pressure process such as a traditional refinery operation. Renewable diesel can be used in diesel engines at blends up to 100%.

-- Follow the latest from Matthew Wilde, Crops Editor, by visiting the Production Blogs at https://www.dtnpf.com/… or following him on Twitter @progressivwilde

[PF_1222]

(c) Copyright 2022 DTN, LLC. All rights reserved.