Succession Strategies Part 2

Cash Is Not Always King

Compensation is a sensitive subject in any industry, but it's especially touchy in a family business like farming and ranching. Agricultural operations tend to be land rich and cash poor. But, there are several ways of looking at compensation besides a cash salary that can help the younger generation feel valued and rewarded for their input, including noncash benefits and equity gifts.

In this second part of Progressive Farmer's Succession Strategies series, we'll explore the complex issues of compensation, management decision-making and training needed to successfully transition the farm to the next generation.

DYNAMIC ROLES DEFINED

The best way to look at this, says Dick Wittman, a farm business and succession consultant since 1980 and retired manager of his family's dryland crop, range cattle and timber operation in northern Idaho, is to review each person's "rewards," which he defines through the three dynamic roles in the family-farm business:

1. The "family" role, which he calls the Circle of Love, is characterized by caring and support, and rewarded by love and gifts.

2. The "business" role, the Circle of Competence, is when performance is tied to objective standards and rewarded by salaries, wages and benefits.

3. The "ownership" role, the Circle of Control, is characterized by wise and prudent control of equity and rewarded through return on investment and dividends.

Sometimes, farm families don't separate these roles, and it can divide a family if the argument becomes, "You don't pay me enough because you don't love me" (not actually said but implied). Or, "You won't let me have more equity because I don't come to work before 9 a.m."

Having a well laid-out compensation structure, Wittman says, with written job descriptions, market-based compensation and regularly scheduled job performance reviews keeps the salary/wage/benefits discussion clearly in the "business" role and help keeps some of the emotion out of the discussion.

NONCASH BENEFITS

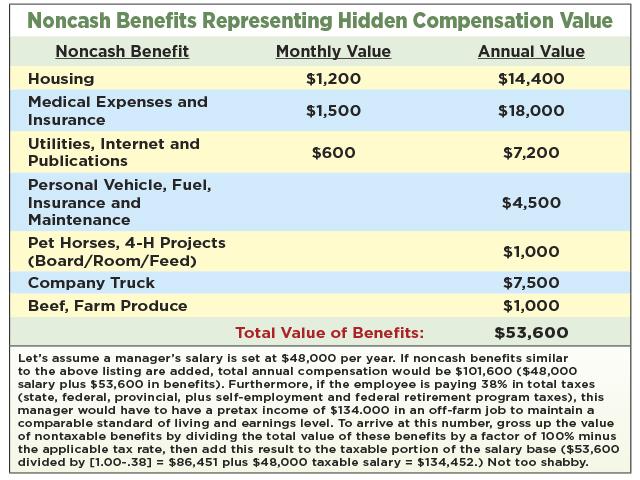

Also, consider under the business role the multiple noncash benefits a family-farm business should factor into the compensation package, he advises. "You need to add in the cost of housing, medical insurance, vehicles, horse boarding, farm produce and anything you don't include in a W-2 wage statement." In his example (see chart accompanying this article), these intangible benefits can tally over $53,000 pretax. If you had to pay for those items after tax on your salary, that would add another 38% to the total.

In Wittman's example of a farm manager being paid $48,000 per year, adding in the noncash benefits provided by the farm business would equate to about a $135,000 off-farm salary.

P[L1] D[0x0] M[300x250] OOP[F] ADUNIT[] T[]

He emphasizes the compensation should be commensurate with the duties and performance of the employee.

COMPENSATE WITH EQUITY

Another option for noncash compensation is gifting equity in the farm business. Often, farm owners will form a limited family partnership or a limited liability company, and gift ownership interests to their children as a way to reduce their estate subject to estate taxes. However, this strategy can also be used to compensate an on-farm heir for his or her "sweat equity."

In 2022, the annual gift tax exclusion amount is $16,000. So, Mom and Dad could gift up to $32,000 in ownership interests per heir to compensate for "sweat equity." The amount could actually be even more since IRS allows a valuation discount because of lack of control and limited marketability in family partnership interests. Expert tax counsel is strongly advised when using this strategy.

A BIG PILL TO SWALLOW

Jeff and Roxi Thompson, who farm in Harmony, Minnesota, wanted to keep expanding their business and bring the next generation into their operation. "Our son, Tom, was farming with us on the side while he went to school to be a John Deere tech. After a couple years, he said, 'If I don't come home to farm full-time, we'll never expand to where we want,'" Roxi Thompson recalls. "He was right. I give him credit for speaking up.

"When he came back, we paid him a manager's salary. That was a big pill to swallow," she admits, "but it was the right thing to do." With Tom's agronomic input, the Thompson farm increased yields, and the family was able to expand its acreage 50% and, within a couple of years, doubled their farm acreage.

If you have more than one heir coming back to the farm, Wittman says not all family members warrant equal pay. "You need to look at their skill sets, job responsibilities and tenure. That's what other businesses do."

For Dave Lubben, who farms with his daughter, son-in-law and son in Monticello, Iowa, the dispute about who was putting in more hours was settled by paying by the hour and keeping track of hours worked via a cell phone app. "We clock in when we show up and clock out when we leave. So, if you're not working, you're not getting paid. We found out I put in more hours on the farm than the younger generation, because I rarely take weekends off, and they occasionally like their weekends off," says Lubben, who often gets the cattle-feeding weekend chores.

TRAINING A MANAGER

Payment isn't the only measuring stick in valuing the next generation. Giving them management opportunities is also important in ensuring a successful transition in a farm operation.

It's important to train the next generation to be a manager, advises Ethan Smith, family business consultant with KCoe Isom. "There is a big difference between a laborer and a manager."

"I view myself as a coach and a mentor to my children," Lubben notes. "If my son says, 'I've got this new idea,' we'll try it out on a test plot and see how it works. I'm willing to try new ideas on a small scale first."

You need to give your child the opportunity to make small mistakes, notes Patrick Hatting, Iowa State University Extension farm management specialist in central Iowa. "You may be quicker at fixing things, but stop and ask your adult child, "What do think?" Give them the opportunity to take a leadership role. Your attitude should be, 'Let's give it a try.' Let them learn by making small mistakes," he advises.

Depending on the interest and skill set of your adult children, some decisions are easier to relinquish control than others.

"With agronomy in row crops changing so fast, it was easy for us to put our son, Tom, in charge of agronomy. And, he's been making tremendous progress on yields by fine-tuning nutrients and changing row widths," Roxi Thompson explains. "He's also taken on the lion's share of responsibility for marketing our grain.

"However, if I got hit by a bus, the business would be in trouble. None of the other managers know how to pay a bill," she admits. "I need to do a better job in pulling Tom into the process of putting together the budget, communicating with the lender and running our financial software."

EXECUTIVE TRAINING PROGRAM

Running a successful business demands lifelong learning. And, in agriculture, there are plenty of opportunities to learn new techniques, skills and ways to operate a business through workshops, seminars and conferences sponsored by state Extension services, lenders, commodity groups, farm input companies, brokerage firms, agricultural consulting companies and agricultural media companies.

Allowing your farming son or daughter to attend educational seminars is another way to value their contribution to your farm.

One of the most intensive and extensive agriculture business training courses for mid-level farm business managers is The Executive Program for Agricultural Producers (TEPAP), coordinated by Texas A&M University. For one week in January (Jan. 8-14, 2023) in Texas, participants get master-class-equivalent instruction in family business management, financial and strategic management, negotiation techniques, succession planning, employee relations, sales, leadership and macroeconomic outlook. It's a two-week course with Part 1 the first year followed by Part 2 the next.

The program is not geared to those early in their farm careers but to mid-level managers who have been farming around 10 years or more, and are willing to invest the time and money to advance to the next level of managing their business.

**

For Part 1 of this series, please go to https://www.dtnpf.com/…

[PF_0922]

(c) Copyright 2022 DTN, LLC. All rights reserved.