Succession Strategies Part 1

Fair Is Not Equal

Major milestones in a farming career can get your heart pumping with excitement -- as a youth driving a tractor by yourself for the first time, coming back to the farm as an adult, selling grain on your own or buying your first farm. As you near retirement age, however, the next milestone is often approached with trepidation -- planning and executing the transition of your farm to the next generation.

Succession Strategies is a series of articles being introduced in Progressive Farmer to help you approach this signpost with knowledge and insight to avoid a family breakup and provide as smooth a transition as possible. That's a tall order for many farm families, but it can be done.

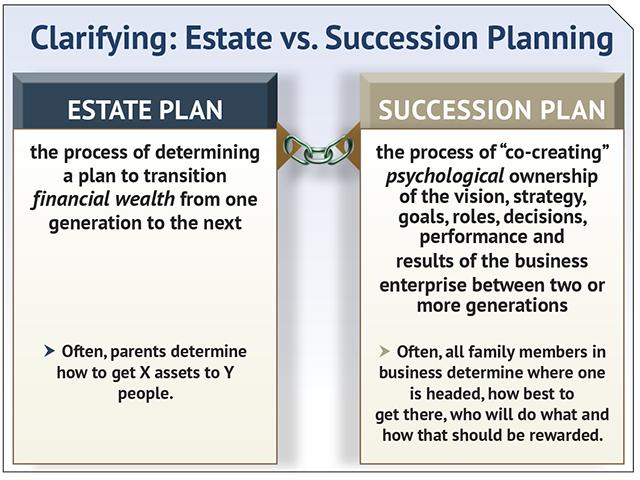

First, a few definitions: Estate planning is not the same as succession planning. Estate planning transfers assets. Succession planning transfers an operating business. Estate planning is relatively straightforward, especially if you have no on-farm heirs. It involves wills, trusts, life insurance, taxes, information you can find at various workshops sponsored by banks, farm consultants, insurance agents, university Extension offices and online.

The thrust of the Succession Strategies series will concentrate on the more complex issue of transitioning your farm business to the younger generation.

The first step is identifying your successor for the farm. Sounds easy enough -- it's your oldest child or the child who has followed you around the farm since he or she was 7. Right?

Not necessarily. Patrick Hatting, Iowa State University Extension farm management specialist in central Iowa says to take a closer look. "Do they have the passion, the intellect and the will to succeed on the farm?" he asks. "They've got to be willing to work long hours for low pay and not gripe," he explains. The older he gets, the more Hatting finds that passion in the next generation is the key to putting in the hard work necessary to survive the risks and profit cycles that inevitably come in agriculture.

For those who are handing over the operating business to the next generation, you need to take a closer look, too. Can you afford to bring the next generation into your operation? Are you willing to give up some of your income? What enterprises can you add that the younger generation can contribute to the farm operation and help cover their living expenses? All are important questions, Hatting explains.

He recalls an example when one eastern-Iowa farmer estimated his operation invested $1 million to $2 million in additional land and livestock for each of his children who returned to the farm to generate enough income to support them. The farmer admitted it wasn't cheap and increased the farm's debt load.

P[L1] D[0x0] M[300x250] OOP[F] ADUNIT[] T[]

Let's say you've already got an on-farm successor, and that person is working out OK. In future articles in this series, we'll explore ways to successfully train, compensate and communicate with your successor.

CONFLICT OR UNITY

For now, let's focus on the big picture: family unity. Your mantra, farm succession-planning experts believe, should be "Fair does not mean equal."

The main conflict for most farm families comes between the on-farm heirs and the off-farm heirs. Some on-farm heirs think they are entitled to all the land and equipment they used in farming when Mom and Dad were alive. Some off-farm heirs think they are entitled to an equal share of all Mom and Dad's assets.

Horror stories abound about farm families feuding over inherited land. In one case, a farmer took his sibling to court several times to get the entire farm. He lost every time, costing him $75,000 in legal fees.

"I encourage families with on- and off-farm heirs to forget 'equal,'â??" explains Alan Hojer, legacy consultant at First Dakota National Bank, based in Yankton, South Dakota. "Their legacy should be about being 'fair.' It's about defining fair. And, in defining fair, it's OK not to be equal."

Hojer advises some farm families to value the farm at some point when all the children were home living on the farm. "There was a point when they were all there. At that point, they each had an equal stake (or no stake) in the farm." Then, there is a point where someone stayed and helped build the farming operation. The off-farm heirs had no hand in that. So, the increased value should go to the person who helped build the wealth, he contends.

DIFFERENT DEFINITIONS

Other families define fair as doing what it takes to keep the farm operation successful. If that's Mom and Dad's goal, off-farm heirs may only receive a discounted value of their share of the farm or a smaller portion of Mom and Dad's assets.

How is that fair? Dave Lubben, who raises corn, soybeans and hay, and has a cow/calf operation with his son, daughter and son-in-law, gives this example: "Let's say the off-farm child makes $65,000 to $70,000 per year. The on-farm child makes only $30,000 in wages but receives $35,000 to $40,000 in farm corporate stock for 'sweat equity.' They wind up with a bigger share of the farm."

Lubben adds farmland that isn't sold is only worth what it can produce. "Just because a broker says it's worth $15,000 per acre doesn't mean it's worth that much if it is never sold," Lubben notes.

Another farmer going through a difficult estate settlement with his family agreed fair does not mean equal. "Did the off-farm heir wake up at 4 in the morning to load hogs and get rammed against the panel by an ornery hog?" asks the farmer who did not want to be identified. "There are risks on the farm that you don't get compensated for along the way. And, if it went the other way, would they feel 'entitled' to help pay off a farm debt of $2 million to $3 million?"

Emotions run high on this issue. "Once a family figures out that it's not about 'equal,' the tension goes away," consultant Hojer explains. "Up until that point, they have this internal battle going on about how can they keep the farm together and equally compensate the off-farm heir."

And, there are other things to consider when treating heirs fair but not equal, he adds, such as if an heir has special needs or mental-health issues, substance abuse or spendthrift tendencies.

"I haven't met a parent yet who doesn't want to enhance the lives of all their children," Hojer notes. "People are on a mission to find peace and purpose to their life. It's a journey," he says. Setting up and communicating a succession and estate plan can help maintain that peace and purpose into the next generation.

[PF_0822]

(c) Copyright 2022 DTN, LLC. All rights reserved.