Kub's Den

Hog Market Needed Clearer, Faster Prop 12 Signals

Lean hog futures prices have hit another patch of volatility -- mostly downward volatility, like last Thursday's (Aug. 19) $2 drop -- and although it's impossible to point the finger at any singular, certain bearish influence, it does make you wonder, as 2022 inches closer, if the markets themselves are finally starting to reflect the uncertainty and industry-wide angst that results from California's Prop 12 measure.

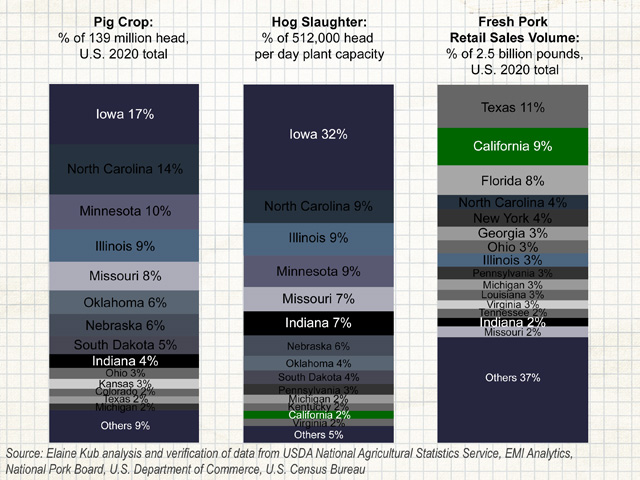

So far, most of the worry for the pork market has been centered on California itself, which voted in 2018 to pass the Farm Animal Confinement Proposition (Prop 12), making it illegal, starting in 2022, to sell pork inside the state unless it can be documented that the pork comes from an animal that was farrowed by a breeding sow that had at least 24 square feet of pen space (and other requirements). Not much of the pork currently available in the United States meets those requirements, so the state of California is expected to experience a dramatic shortage in some of its favorite meats, driving the prices of bacon in the grocery stores and carnitas tacos on the streets of Los Angeles sky high. (https://apnews.com/…)

There are still legal efforts that may prevent California's Prop 12 from disrupting the nationwide pork supply chain (see https://www.dtnpf.com/…), but if it can't be stopped, those of us in the rest of the country need to get ready for a sudden collapse in demand for pork from conventionally-raised hogs. Data from the National Pork Board's Pork Checkoff shows California represented 8% to 9% of fresh pork retail sales and total pork retail sales in 2018, 2019 and 2020, both by dollars spent and volume purchased. Other estimates have suggested California accounts for as much as 15% of the nation's pork consumption. However we slice the ham, if the traditional U.S. pork market suddenly loses 9% to 15% of its customer base because those customers won't be able to legally purchase pork from conventionally raised animals, then prices will fall. There will effectively be two separate pork supply chains -- a high-priced, scarce supply of Prop 12-compliant pork destined to be sold inside California and a glut of oversupplied conventional pork flooding cold storage everywhere else.

P[L1] D[0x0] M[300x250] OOP[F] ADUNIT[] T[]

Lean hog prices typically trail the pork cutout by about $5 per hundredweight. So, if wholesale pork averages about $75 per cwt, then nearby lean hog futures would be expected to trade around $70 per cwt. This week, October pork cutout futures are around $101 per cwt and October lean hog futures are around $88 per cwt. That's a $13 spread, but even that is well within the range of what is sometimes seen in this market, especially in comparison to mid-2020 when packers were struggling to stay open during the COVID-19 pandemic. The average spread through 2020 was $16 per cwt and the worst was $56 in mid-May when pork ($114 per cwt) was hotly demanded at grocery stores but overweight hogs ($58) had to be turned away from some packing plants and destroyed because there simply wasn't enough capacity to process all the animals that reached their market weight on a biological schedule that had been set in motion months before.

Not to get too apocalyptic about this California Prop 12 scenario, but one wonders just how much damage could occur to the lean hog market in January 2022 when the law is scheduled to go into effect. As long as the packing plants stay open and continue to process their usual volume of hogs (approximately 470,000 head per day lately), things should be fine. But without California's 9% to 15% of U.S. demand, what happens to all that pork? Some of it can be exported, sure; some of it can be stashed away in cold storage. But at some point, any market that is oversupplied with a commodity -- in this case, market-weight lean hogs -- will eventually push back with lower prices. Looking at history when the hog market was oversupplied, like 2016-18 when swine herd expansion outpaced slaughter capacity growth, we might expect prices to drop 10% to 20% compared with the pork cutout.

The problem with all of this is the uncertainty. If the industry had known all the details of Prop 12 compliance several years in advance, or even now, if we knew for sure what was going to happen in January 2022, then we would expect the market to work in an orderly way to motivate an appropriate-sized shift from conventional hog production to Prop 12-compliant hog production, and a subsequent reduction in conventional hog production, forestalling any concerns about a sudden glut of oversupply in early 2022. Unfortunately, those market signals haven't happened, or haven't happened clearly enough or fast enough. In fact, Iowa State University's latest estimated returns for a conventional farrow-to-finish operation remain above $50 per head -- highly motivating to expand production, not reduce it. Their estimated returns for hogs sold in June 2021 were $63 per head -- the most profitable this industry has been since August 2014.

Pork that will be on sale in U.S. grocery stores in January 2022 will come from hogs that are slaughtered and processed in December 2021. It takes approximately 17 weeks to finish a hog on calibrated feed rations to reach its target market weight, so those hogs are just now being moved to finishing barns. Prior to that, the animals spent approximately six weeks in a nursery, and before that, approximately three weeks in a farrowing barn from birth to weaning. Therefore, the hogs in question were already born in mid-June. Their sows -- the animals whose production practices determine whether the ultimate product will be Prop 12 compliant or not -- were already bred back in February. Whatever market signals hog farmers needed to receive to adjust their production quantities in a non-chaotic way, they would have been needed months ago. It's too late now to avert the coming crush of conventionally raised pork that will have to be absorbed by the non-California rest of the world. Pork cutout futures have some open interest for the October ($100 per cwt) and December 2021 ($95 per cwt) contracts, but nothing past that yet to indicate the market's price expectations.

Pork packing companies have been communicating with the hog producers who supply their animals to determine what proportion of their market will be Prop-12 compliant by early 2022 and to offer premium bids for such animals, which will be tracked and processed through a separate supply chain destined for the California market. Individual producers have been making decisions about whether those premium prices will be enough to offset the expenses of retrofitting farrowing barns with the necessary group housing arrangements. Packer-owned hog production facilities themselves are perhaps best placed to take advantage of the premiums, having more certainty about what will be required to reach the California market and what the financial rewards might be. In March, Rabobank analysts estimated less than 4% of U.S. sow housing was able to meet the Prop-12 standards. By now, it's likely that portion is somewhat higher after months of frantic installation of new sow feeding and handling equipment across the country. But will it be enough to meet the sudden shift into a two-path U.S. pork supply chain? So far, the futures markets have been only tentative at signaling what might happen.

Elaine Kub is the author of "Mastering the Grain Markets: How Profits Are Really Made" and can be reached at masteringthegrainmarkets@gmail.com or on Twitter @elainekub.

(c) Copyright 2021 DTN, LLC. All rights reserved.