Family Legacy Retraced

The Land Still Calls

I'm standing on a rise in a grassy pasture on an early-summer morning in southeast North Dakota, near the tiny town of Fullerton. The air is still, but the temperature is pleasant -- about 70°F.

I try to imagine being here long ago under the very different circumstances faced by my great-grandparents, Peter and Nellie Welander. This is the site of my ancestors' original 160-acre homestead, established in the fall of 1897.

Only months after filing their paperwork with the county -- and in the grip of winter in early 1898 -- the farm well is frozen. The sudden lack of water was an emergency for both them and their livestock.

Peter Welander loaded empty barrels onto a stone boat, a horse-pulled sled on skids so-named because it was most often used to haul rocks out of fields. Then, he, along with 7-year-old son, Palmer, trekked more than three miles cross-country before the gradual descent into the wide valley, shaped by the James River.

A MATTER OF SURVIVAL

Once at the river, the pair were filling the barrels when the ice gave way, and Peter dropped into the freezing water. Chances are the river was only a few feet deep near the shore. Wringing wet, he managed to clamber out of the water but immediately was facing life-threatening, subfreezing temperatures.

Could Peter dry off with anything? Did they finish filling the barrels? Maybe so. After all, the farm still desperately needed water. We don't really know. Then there was the trek back to the farm. We do know they made it home.

But, the success was short-lived. Within three days, Peter took ill and died of pneumonia.

RETRACING STEPS

Now, 125 years later, I'm about to duplicate the hike -- minus the stone boat and fall into icy water -- from the old farmstead to the river.

There is just enough evidence at the site to indicate there was once a homestead. A pile of field rocks, a metal headboard and an old piece of field equipment mark the location. The implement is a grain drill from Monitor Drill Co., once based in Minnesota, which ceased doing business in 1929.

There hasn't been a structure on this spot for 70 years. I knew it was the right place according to the original county plat maps but also because of the knowledge of Joey and Trista Gemar. They are the young farmers (not my relatives) who now own the land.

P[L1] D[0x0] M[300x250] OOP[F] ADUNIT[] T[]

"I couldn't imagine trying to raise a family of six on a quarter section of land now," says Joey Gemar. "Our family oversees the church cemetery, and I look at those gravestones and wonder how so many of them lived as long as they did. This wasn't an easy life."

Certainly not. Hardships that seem unimaginable today were considerably more commonplace then.

As a result of Peter's death, 9-year-old Alfred (my grandfather and the eldest of five siblings) had to quit fifth grade to work their farm. His mother also hired out Alfred as a laborer to other operations to help make ends meet.

As a young adult, Alfred would eventually purchase a nearby quarter section, while his younger brother, Palmer, continued to work the original farm. Alfred married my grandmother, Ethel, in 1912, and by 1916, they built -- mostly by themselves -- a blacksmith shop and a barn. Both buildings still stand today on the Gemars' farm.

STORIES TO TELL

The Gemars love the common history of the farm on which they raise four children. "I wish I knew as much about my own family history as I do yours," Trista tells me. "Down the road, we may have a child or grandkids that live on this farm, and it is pretty amazing to know the stories."

And, there are plenty of those. My grandmother, who grew up one of 13 children on a farm in Ontario, Canada, was sent to live in North Dakota at age 15 to keep house for a 17-year-old homesteading brother. Teenaged Ethel thought she had been exiled to the ends of the earth on North Dakota's treeless prairies.

The farm of Ethel and Alfred, within sight of the original homestead, was the epicenter of myriad stories in which our family is immersed. There were tales of milking cows, caring for and butchering chickens, helping tend Jersey-Duroc pigs, a legendary battle with a marauding badger, living with no indoor plumbing or electricity, and walking cross-country to the one-room township schoolhouse.

REFLECTIONS

Using the field boundaries as a guide, I begin hiking from the homestead to the James River. The biggest danger I'll potentially face is accidentally breaking an ankle by stepping into one of the numerous pocket gopher holes along the field edges.

Today, corn has largely replaced the small grains like wheat, oats and barley that grew here 125 years ago. Homesteading in the region began in the 1870s but took off in earnest in the 1880s as rail lines proliferated, and the railroads -- along with the federal government -- promoted homesteading and town-building along the routes.

My boots and pant legs become soaked with dew as I consider the daily struggles of the pioneers. But, I also can't help but think of the tragedy suffered by the previous residents of the region: Native American people. Nearly all of them were pushed further west or north, sent to reservations or killed so the railroads, homesteaders and eventually towns could move into the region.

In fact, the deadliest "battle" between the U.S. Army and Native Americans in North Dakota history took place in 1863 not 20 miles from where I'm hiking, at a place called Whitestone Hill. In essence, the fight was little more than a massacre as troops attacked a village of 4,000 Sioux, mostly members of the Yanktonais and Hunkpatina bands. As many as 300 men, women and children were killed, along with at least 20 soldiers.

As a result of this bloodshed and others in subsequent years, settlers began to take over the lands.

The town nearest the farm, Fullerton, was surveyed in 1887, and North Dakota became a state in 1889. In October 1897, Peter and Nellie (Tangen) Welander filed a land patent to homestead a quarter section (160 acres) under an 1873 federal act to "encourage the growth of timber on western prairies." The two had emigrated to the U.S. years before -- Peter from Sweden and Nellie from Norway.

I'm out of the corn fields at a high point along a gravel road now, and I can see the James River below in the distance. Peter and Palmer would have likely cut across the couple of farms in between, but I hadn't contacted those owners, so I stick to the road and end up on a newer bridge spanning the waterway.

Looking back in the direction from which I'd come -- and assuming the meanders of the river were similar in 1898 -- I see a spot about 80 yards away that would have been the closest point for my great-grandfather to reach the ice-covered waterway.

The idea Peter would have hiked back home with a stone boat full of water and a small son in tow while wet in freezing weather seems heroic, but he had no other choice.

As for me, I call the farmer, Joey Gemar, to come pick me up for a ride back to the farm.

FINAL THOUGHTS

Palmer Welander would work the original farm into the 1940s, and the operation/land would eventually be sold to his brother, Alfred. The eldest of my generation, Ron Willardsen, 80, remembers being around both farms as a young boy.

"When the sun came up, you went to work," Willardsen says. "I remember holding the tails of the cows while they were being milked, gathering eggs with Grandma Ethel and being introduced to the hoe in the garden."

Despite never returning to school, Alfred would go on to design and build a special eight-sided building to farrow Jersey Duroc pigs, help originate, in 1937, the North Dakota Winter Show (which still takes place annually) and be named Farmer of the Year in 1947 by the Saddle and Sirloin Club at North Dakota State University.

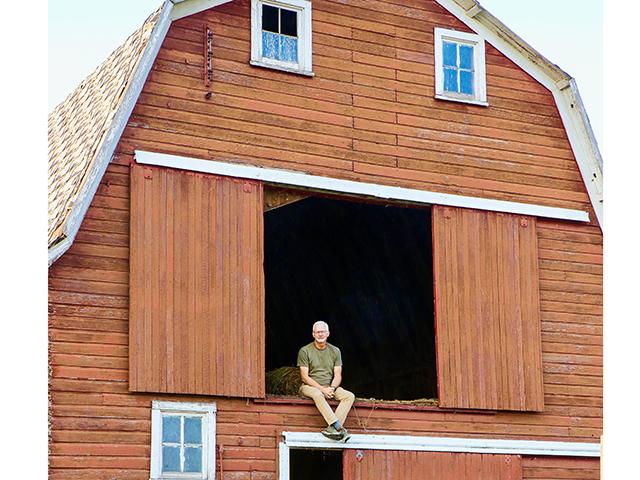

After a sublime homemade dinner at the Gemars' house, we poke around the old barn and the blacksmith shop. The blacksmith shop is tiny and much the worse for wear. The barn's 107-year-old bones are very sturdy, but even Joey confesses: "I'd scarcely been in the barn since we bought the farm." They've never had livestock until recently.

Their children keep a couple of 4-H calves in the barn along with a horse. It's a good bet that horse will never have to be hitched up to a stone boat as part of a life-saving mission to a river beyond our sight.

**

Watch the video: https://www.dtnpf.com/…

[PF_0523]

(c) Copyright 2023 DTN, LLC. All rights reserved.