Kub's Den

Insanity of Paying 7% on an Asset (Farmland) That Only Earns 2%

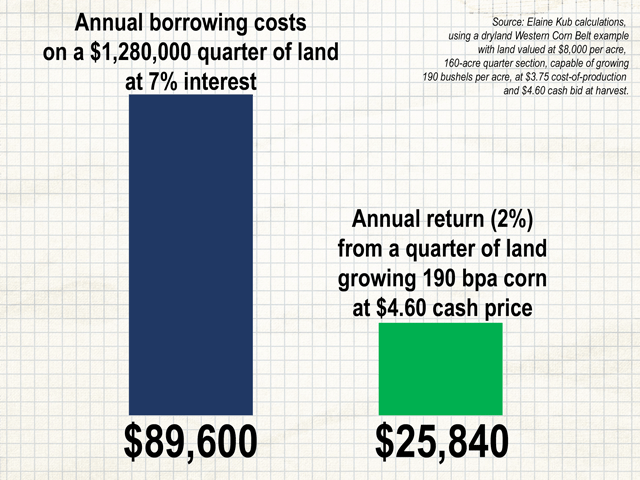

"Don't pay 7% to buy an asset that will only earn you 2%." Straightforward enough, as financial advice goes, but this simple statement landed like a ton of bricks when it was offered to a conference of young and beginning farmers in Omaha earlier this year.

To a roomful of people who want to build their farming businesses by buying land, it was almost like saying, "Give up on your dreams." The advice-giver was Chad Gent, senior vice president of retail credit at Farm Credit Services of America, who actually doesn't believe it's impossible for young farmers to start building a land base, and who has much more nuanced insights about borrowing money and buying farmland in the present environment.

However, when it comes to the reality of how much profit is available on high-priced farmland these days versus the costs and sacrifices required to make those profits, no one can deny it's a challenge.

Here's an example I used while checking the math: Let's say a young farmer could buy a quarter section (160 acres) of non-irrigated land somewhere in the Western Corn Belt for $8,000 per acre. If the mortgage was leveraged 100% with no down payment, and the interest rate was 7%, then the annual debt service on that mortgage would come to $89,600, and that's without considering property taxes or any other cash outflows required. Against that, a farmer might grow 190 bushels per acre of corn on that land and sell the corn for $4.60 in today's market. However, if the cost of production was $3.75 per bushel (a pretty generous assumption), then the farmer's net cash inflow would be only $25,840, or 2% of the value of the asset. Quite a mismatch.

Your mileage may vary -- you could be in a region with land at $2,000 per acre or $12,000 per acre -- but in any example you use, the costs of borrowing money to buy farmland at today's record-high land prices far outweigh the returns of growing commodity grain at today's grain prices.

P[L1] D[0x0] M[300x250] OOP[F] ADUNIT[] T[]

Even for an investor who never intends to set foot on the land, if they're paying $89,600 annually in interest payments, then they have to receive annual cash rent of at least $560 per acre for their cash flow to break even. I know cash rents have been going crazy, but I have yet to see something quite that crazy.

As Chad Gent at Farm Credit Services pointed out, however, "Buyers aren't only looking for an annual cash return from their asset, they're also looking -- and speculating to some degree -- on the long-term capital gain in the value of the asset. For investors, farmland has become an almost trendy alternative investment, and buyers are still really bullish on the capital gains piece because they feel confident the exit price won't go down from where it is today. Quality farmland never depreciates."

This is true not only for out-of-state investors but also for local farmers who may bid willingly for farmland at record-high prices with full knowledge of the grim cashflow prospects. "Established farmers may be thinking of owning land over multiple generations," Gent explained.

So, should farmland prices come down? Is there a bubble that might collapse if everyone in the market suddenly realizes how untenable it is to pay these all-time high land prices? Gent says, "Long term, we typically see farmland returns tracking 10-year Treasuries, which are at 4.4% today. If they get separated, they usually come back together eventually, but they are just so far off today."

One way to see annual returns on farmland improve would be to see land prices suddenly collapse. This seems unlikely, given the supply and demand balance -- both the scarcity of land available for sale and the eagerness of buyers willing to snap up whatever is offered. Another way, of course, would be to see crop prices grow dramatically higher. You can argue all you like that the justified price for the drought-affected 2023 crop should be higher than it is today, but despite any arguments, it's just not, at least not yet. And when thinking about a long-term commitment like a farmland mortgage, buyers need to be making projections not only for this one year's crop but for the next 30 crops. Cash corn at $4.60 for the next 30 years would, frankly, be a gift.

I know from my email inbox that the readers of this column get annoyed and upset when it reveals uncomfortable truths about commodity prices moving lower historically and dipping below many producers' cost of production. This is especially challenging in today's environment when all the inputs' underlying costs keep increasing. Therefore, I can't imagine anyone is going to enjoy reading this, either.

In fact, I suspect readers who want to buy land will find it even less enjoyable because buying land is emotional. It may feel like you only get one chance in your lifetime to own a parcel of farmland when it comes up for sale, and there are so many aspirational examples of wealth being built as the result of land ownership. The idea of not bidding, just because the price is too high or the interest rate environment is unfavorable, may feel like missing out or giving up.

Chad Gent counsels that it is still possible for even young and beginning farmers to get started on land ownership in today's conditions. "Don't give up; building a land base is a valuable long-term pursuit. Just don't take a bigger bite than you can chew. Debt can be great to accelerate growth, but when you have limited capital, you must be careful how you deploy debt. Without the discipline to avoid buying parcels of land that are too big or equipment that is more expensive than you really need, debt can sometimes accelerate failure instead of growth." His advice to young and beginning farmers is to start with agricultural opportunities that don't require a big land base, like custom work or animal feeding.

"Take your energy and intelligence and creativity and put it into a business model that will leave you ready for future opportunities someday, without overleveraging now and sacrificing the whole dream."

**

Comments above are for educational purposes only and are not meant as specific trade recommendations. The buying and selling of grain or grain futures or options involves substantial risk isn't suitable for everyone.

Elaine Kub, CFA is the author of "Mastering the Grain Markets: How Profits Are Really Made" and can be reached at analysis@elainekub.com.

(c) Copyright 2023 DTN, LLC. All rights reserved.