Kub's Den

Commodity Market Volatility Possible as December Contracts Go Into Delivery

You know that classic fear of first-time futures traders, that someday they will end up having to pay for 5,000 bushels of real, actual, physical grain instead of merely taking a financial profit or loss as the price of a futures contract changes? Well, now we're in the timeframe when that can become a reality for traders who still have open December futures positions, which will expire in two weeks.

First Notice Day for December corn, oats, wheat, soybean oil and soybean meal was Tuesday, Nov. 30, meaning anyone still holding a long futures position in these contracts could end up paying for and owning the physical stuff, if the other traders still holding short positions decide it's in their best interest to deliver the grain and get paid the prevailing futures price.

With grain prices being as interesting as they are these days, it's worthwhile to consider how much of this delivery action may occur this December. So far in their first daily deliveries report for the expiring December contracts, there were unsurprisingly few delivery intentions for corn (only two) and unsurprisingly many deliveries for wheat (1,054 for the Chicago contract and 350 for the Minneapolis contract). That's because cash prices for actual corn located in warehouses along the Illinois waterway aren't terribly far off from the price of the expiring December futures contract. A small number of deliveries show that the futures price is well supported by reality on the ground -- the two markets are already pretty close to convergence. There's not enough of a gap between the futures price and the real cash price to make the paperwork and rigamarole of commercial warehouse delivery worth the effort.

P[L1] D[0x0] M[300x250] OOP[F] ADUNIT[] T[]

On the other hand, a large number of deliveries shows there is an arbitrage opportunity to be made, and the futures price needs to be pressured lower to converge with the reality of the cash market. This may be true for the excitable wheat futures markets lately. Consider December Minneapolis spring wheat futures, at about $10.40 per bushel, when actual cash prices for spring wheat in Minnesota are about $10.00 per bushel. If you were a grain trading company with physical wheat stored in a registered warehouse and a short futures position in the expiring December contract, you'd be happy to issue a shipping certificate, indicating your intent to deliver physical wheat against that position, then get matched by the exchange with someone who's still stuck holding a long December futures position, and ultimately get paid $10.40 per bushel for physical grain that may actually be worth less than that.

Long position holders, therefore, should be highly motivated to get out of those positions so they don't get stuck paying too much for physical grain in an elevator that they don't really want. In that way, the process motivates traders to pressure the expiring contract's price lower to converge with the reality of the physical market.

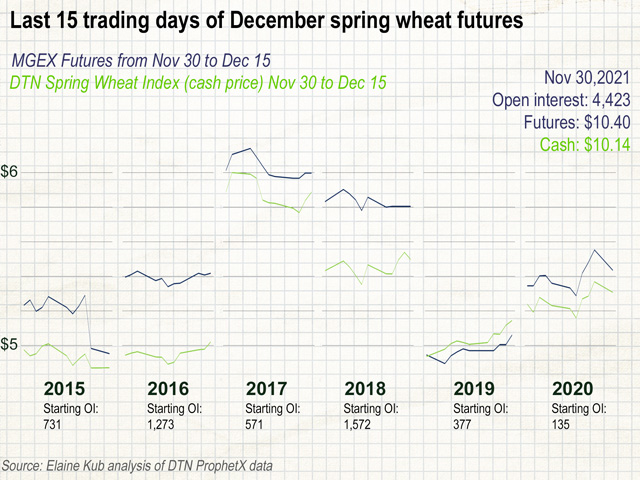

Historically, the last two weeks of trading in the December grain contracts, while they are in delivery, do indeed tend to bring the cash and futures prices closer together, minus some spread for transaction costs or motivation. The most interesting of these contracts this year, in my opinion, is the Minneapolis spring wheat market; it's relatively thinly traded even in the best of times (maybe 20,000 contracts traded on the average day versus 120,000 contracts traded per day in the benchmark Chicago wheat futures market). Once in delivery, all kinds of volatile fireworks could happen day to day.

This is particularly interesting this year because there are still over 4,000 contracts of open interest in the December 2021 Minneapolis spring wheat contract as of First Notice Day. Ordinarily, traders would have exited their trades or rolled over into a deferred contract by now. Last year, when the December 2020 spring wheat contract was expiring, only 135 contracts of open interest remained as of First Notice Day.

Wheat traders, speculators especially, have been herding altogether lately into long futures representing hard milling wheat varieties. As of the Nov. 23 CFTC Commitments of Traders report, "Managed Money" traders owned 21 long spring wheat futures contracts for every short contract (although not necessarily in just the December contract, of course). Within the market for just this December contract, there may now be a rush to get rid of those 4,000 imminently expiring contracts, whether they are long or short. Of course, those getting out of long December positions may simply roll their interest forward into March positions, maintaining the same general stance toward wheat price movements.

Ultimately, the financial fates of individual speculators or grain trading companies who may get stuck taking delivery of spring wheat over the next couple of weeks doesn't do much to affect the real prices paid to other market participants through the rest of the marketing year. As always, it's more important to consider the future prospects of supply and demand for the grain and how that will move the benchmark prices for the March contracts, the May contracts and beyond.

Elaine Kub is the author of "Mastering the Grain Markets: How Profits Are Really Made" and can be reached at masteringthegrainmarkets@gmail.com or on Twitter @elainekub.

(c) Copyright 2021 DTN, LLC. All rights reserved.