South America Calling

Wet Season Rains Diminishing Early in Brazil

As I explained last week in a blog, (https://www.dtnpf.com/…), planting for the safrinha (second-season) corn in Brazil has been delayed. The states of Parana and Mato Grosso do Sul are significantly behind. While planting in Mato Grosso finished close to the normal time, a significant portion of that crop was planted later than normal, especially when compared to last year.

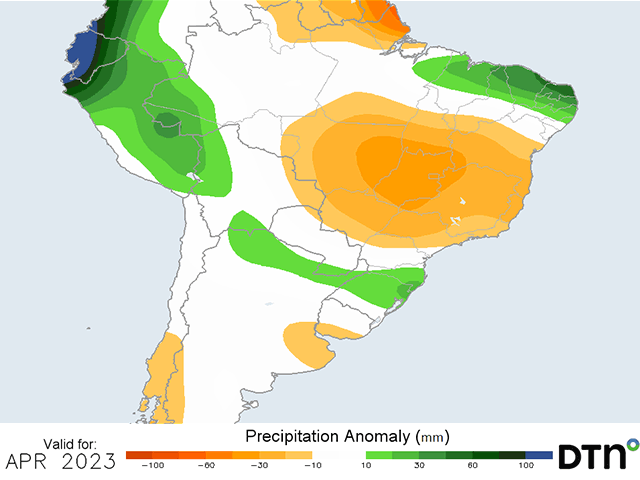

Corn production is going to need to see sustained rainfall for the rest of the wet season, and an extension would be favorable, to not have a concern about production. The wet season typically ends in the middle of Brazil in the first few days of May. That puts the focus squarely on the April precipitation forecast.

Last week, models suggested good rainfall through the rest of March and into early April, with some questions about the end of April. The end of April is still showing those tendencies on this week's model runs. However, models did a quick flip to much drier conditions starting this week.

P[L1] D[0x0] M[300x250] OOP[F] ADUNIT[] T[]

Consistent wet season rains have moved northwest into the Amazon and, as of March 24, are forecast to be much more isolated through the end of the month and into early April. This is of grave importance. If these wet season rains dwindle to measly showers for the bulk of April, we would expect to see reduced corn yields for Brazil farms.

In 2022, wet season rains ended in a somewhat similar fashion. The heavy, consistent rains ended in late March, and very isolated showers continued into April. There was a period in mid-April that did produce a brief period of good precipitation, but the wet season ended for all intents and purposes in late March. Luckily for Brazilian producers, they planted their crop on-time or even slightly early. Around 50% of the safrinha corn crop was planted in early February 2022, but that same progress was about two weeks later in 2023. With temperatures routinely touching the lower to middle 30s Celsius (upper 80s to mid-90s Fahrenheit), crop stresses increase quickly when rains do not occur.

Brazil counts on wet season rains to get the crop through pollination before they shut down and the crop has only subsoil moisture to draw from to fill grain. When the wet season ends early, as it did in the 2020-21 and 2021-22 seasons, potential production will suffer.

USDA estimates that Brazil will produce 125 million metric tons (mmt) of corn for 2022-23, an increase of 9 mmt from 2021-22. Given somewhat similar conditions or worse conditions than last year, there is room for these numbers to go down should the forecast for April verify drier than normal.

Historically, there continues to be a greater risk for frosts in June as well. 2022 did not see those frosts come to fruition in a meaningful way that 2021 did. If they do occur this year, given the later plantings, there is still room for a lot of weather risk to inject itself into corn production beyond just the potential rainfall deficits.

To find more international weather conditions and your local forecast from DTN, visit https://www.dtnpf.com/….

John Baranick can be reached at john.baranick@dtn.com

(c) Copyright 2023 DTN, LLC. All rights reserved.