Kub's Den

Interest Rates Add to Cost of Production

"The increase in interest costs year over year for the 'average farm' has been roughly equivalent to a yield loss of 2 bushels per acre." This was a comment made by Nate Kauffman, senior vice president and Omaha branch executive at the Federal Reserve Bank of Kansas City at a recent presentation. It's shocking when you hear it put that way; rather than keeping the income from those 2 bushels per acre (bpa), farmers are now paying that value to a financial institution in an interest rate environment that is dramatically tougher than it was a year ago at this time ... and probably going to get even tougher yet this week.

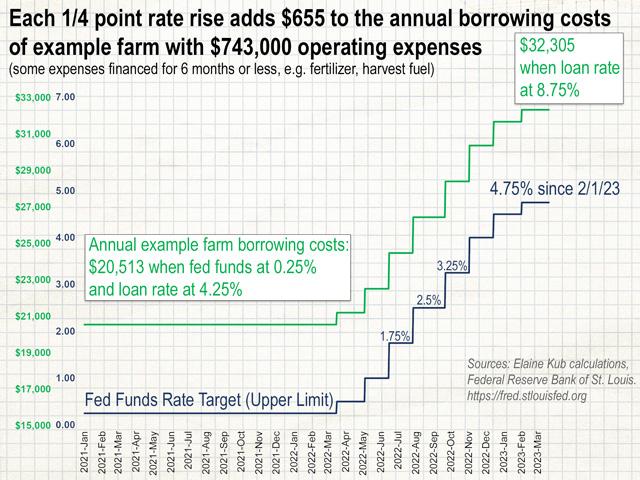

Roughly a year ago, the target fed funds rate was still lingering at 0.25%, the same easy-going, almost-zero level where it had been parked since March of 2020. But starting on March 16, 2022, the U.S. Federal Reserve began a series of rate hikes meant to cool down overheating inflation, going from 0.25% to 0.50% to 1.00% to 1.75% to 2.50% to 3.25% to 4.00% to 4.50% to 4.75% at the start of last month. If a farm is financing its operating expenses with a note set at "Fed Funds Rate plus 4.0%," for instance, then it could be paying 8.75% interest on the various input costs that go into growing crops.

Of course, there is no perfect measure of what an "average" farm is, or what the "average" interest rate is on the operating notes of these "average" farms. Some FSA Direct Operating Loans may still offer an interest rate as low as 4.75% (but only up to a $400,000 maximum loan size), and some borrowers with certain financial characteristics may be borrowing money at 11% or more.

For the purposes of illustrating how this week's potential rate rise could affect the "average" farming operation, I made some calculations assuming a 1,000-acre grain farm in Iowa requires $743,000 in total annual investment to grow 91,000 bushels of corn and 26,000 bushels of soybeans in 2023. This farm wouldn't need to borrow all of that money for an entire year; let's say it has some land expense locked in at 4.5%, plus some machinery on their operating note at 8.75% that must be carried over all 12 months of a year, plus some variable costs that only need to be financed for six months or so (seed, fertilizer, etc.), plus some variable costs that only need to be financed for a month or two before harvest income pays off the note (fuel for the combines, etc.). Given these assumptions, and weighted across these borrowing timeframes, this "average" farm might pay $32,305 annually in borrowing costs.

P[L1] D[0x0] M[300x250] OOP[F] ADUNIT[] T[]

That's $11,792 more than they would have paid on the same sized operating note last year -- a 57% increase. Each 1/4-point rate rise adds $655 to the farm's annual borrowing expense. If a bushel of corn is worth $5, then each 1/4-point rate rise eats up 131 bushels of value from the farm.

Last year, it would have taken 4.1 bpa to pay for the farm's borrowing costs, but this year it will take at least 6.5 bpa to pay for their borrowing costs.

The whole calculation is a moving target. There is an expectation that the U.S. Federal Reserve may boost its target Fed funds rate by another 0.25 points to 5.0% on Wednesday, March 22. Meanwhile, the value of a 2023 bushel of corn may itself change dramatically between now and the moment when it's sold ... and the pending Fed rate decision may itself affect that value.

Higher interest rates inherently drive down the value of income-producing assets like dividend-yielding stocks and even land (theoretically) because the assets' future income streams must be discounted and are worth less today given the time-value of money in a higher-interest-rate environment. That's one reason to wonder if the markets will get wild later this week, to say nothing of the potential for continued uncertainty in the banking sector as bond prices fluctuate.

Meanwhile, commodity markets can't necessarily calculate a "present value" of future income streams to be their fair price, but financial markets are more than arithmetic calculations, anyway. If investors are spooked by the Fed's inflation outlook, or by their determination to boost rates despite vulnerable bank balance sheets -- and if widespread market volatility reigns Wednesday and Thursday -- commodity markets, including the grain markets, will be affected too.

**

Comments above are for educational purposes only and are not meant as specific trade recommendations. The buying and selling of grain or grain futures or options involve substantial risk and are not suitable for everyone.

Elaine Kub, CFA is the author of "Mastering the Grain Markets: How Profits Are Really Made" and can be reached at masteringthegrainmarkets@gmail.com or on Twitter @elainekub.

(c) Copyright 2023 DTN, LLC. All rights reserved.