Kub's Den

Late June Crop Condition Is the Moment of Truth for New Crop Prices

Ask anyone who was farming in 2012 what late June felt like, and they'll remember it vividly -- how the weather turned hot but it didn't rain, and how the low-key dread and worry that is always present when a crop is growing in the field seemed to suddenly turn into collective panic all in one day.

June 2012 sticks out in my own mind for another reason too: 10 years ago this month, my book "Mastering the Grain Markets: How Profits Are Really Made" was first published, just in time to ride the wave of frenzied headlines about $7 corn and "food-versus-fuel."

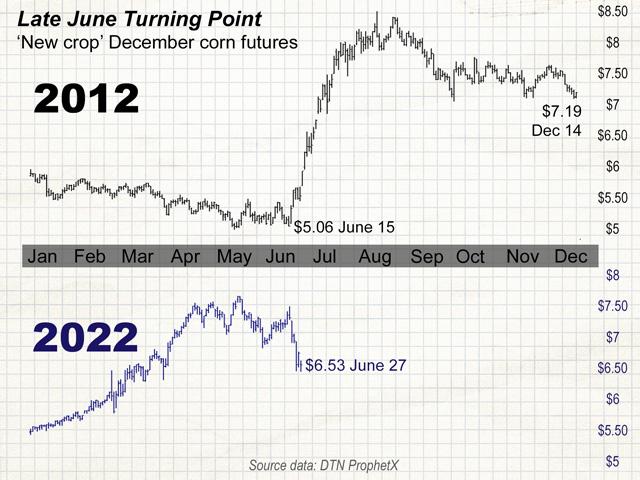

Since that time, I've continued to hear from grateful readers who range from grain traders in Poland or South Korea, cello players in Beverly Hills, big bank analysts on Wall Street and, of course, Midwestern farmers. The grain markets have thrashed through a few summer shortages and languished during the doldrums of normal overabundance. They've seen wet springs, hot summer nights, South American droughts and everything in between. However, for a sheer vertical climb in prices, nothing has compared to the summer of 2012 when the days leading up to the Fourth of July saw corn prices leapfrog gaps higher on the charts and put on nearly $2 per bushel over eight trading sessions.

There is something about this moment in the growing season, when even the late-planted corn is waving knee-high by the Fourth of July, and each producer scouting each field gets a sense of whether or not the crop is going to make it. The rest of the market gets an overall sense of this too.

P[L1] D[0x0] M[300x250] OOP[F] ADUNIT[] T[]

In 2012, the overall sense at this moment was: We are not going to have enough grain.

In 2022, the overall sense seems to be: We're going to make it. There are ongoing bullish influences on global feed grain prices -- inflation, war, etc. -- but it doesn't look like North American scarcity is going to be one of those influences. With the exception of some dry pockets in the West (and North Carolina), the U.S. row crop fields are doing fine -- 67% of corn is rated either "good" or "excellent;" nationwide soybean emergence has caught up to a normal pace, even after the late planting in the northern tier of the Corn Belt, and 65% of those fields are rated "good" or "excellent" too.

In any "normal" crop year, there does tend to be a seasonal pattern in new crop prices, with the markets building in the most risk premium in mid-June when the crops still face the bulk of their weather threats. Usually, that peak in prices can look like the gradual cresting of a hill (reached, on average, around June 18), then a gentle downward coasting until a harvest low is established, and the overall effect may be a subtle path wavering between, say, $3.50 and $4.50 per bushel.

In any not-normal crop year, the grain markets tend to invent much weirder patterns, but they are still influenced by the risks faced by the crop itself and the timing of when those risks change from "uncertainty" into "information." Once the crop's condition becomes reliably observable in late June and much of its yield prospects are already set within the plants, this is the timeframe when opinions about new crop supply are most likely to shift.

Now again in 2022, we seem to be experiencing a late June change in market opinion. That's not to say that another $2 streak (lower this time) is a pre-destined certainty. This move in 2022 may stop with the 57 cents that was lost last week, or it may accelerate during later summer crop tours, or it may just slowly dwindle lower toward harvest -- or there may yet be fresh waves of bullish panic as the world struggles to source its typical flows of food and feed grains during the coming year. Who knows?

Here in the United States, commercial grain buyers have a sense of how much new crop grain farmers have already been confident to commit at relatively high prices and how badly the local market may need it after a depleting summer. Therefore, new crop basis bids offer another source of market sentiment, and they are mostly normal (30 to 40 cents under the December futures contract for the middle of the Corn Belt) or strong (0 to 15 cents under in the dry Southwest near big feedlots). In some cases, they are either predatory (70 to 80 cents under in the Dakotas) or just affected by hefty fuel surcharges in the rail freight rates for grain that must be shipped across long distances. Note that, while the national average cash price for spot corn today remains around $7.50 per bushel, the new crop prices are noticeably less exciting by the time you take a $6.50 December futures price and back off 30 cents ($6.20) or 70 cents ($5.80).

Nevertheless, as we seem to be watching history repeat itself -- but in a reversed mirror image -- there are some timeless lessons that readers of "Mastering the Grain Markets" and of this column over the past decade may have taken to heart. When it comes to the volatile commodity markets, there is a time to buy and, sometimes more importantly, a time to sell.

**

Comments above are for educational purposes only and are not meant as specific trade recommendations. The buying and selling of grain or grain futures or options involve substantial risk and are not suitable for everyone.

Elaine Kub, CFA is the author of "Mastering the Grain Markets: How Profits Are Really Made" and can be reached at masteringthegrainmarkets@gmail.com or on Twitter @elainekub.

(c) Copyright 2022 DTN, LLC. All rights reserved.