Kub's Den

Volatile New-Crop Prices Lead to Higher Crop Insurance Premiums

Due to the nature of physical reality and the inflexibility of the space-time continuum, it doesn't really matter how much corn will be available in this country at 10 o'clock in the morning on Dec. 1, 2021. None of that future corn can be used to meet the demands of livestock feeders and exporters today, or in March, or in July of 2021. The new-crop market and the old-crop market are two totally separate scenarios.

And yet, both markets do tend to move up or down together. The "old-crop" March 2021 corn futures contract, which reflects all the bullishness of last year's production challenges and all the excitement of China's recent buying spree, gained more than $2 per bushel from August to February. The "new-crop" December 2021 corn futures contract gained only 83 cents during that same timeframe.

But why did it gain anything at all? The contract has been traded since 2018 and has generally just displayed the flat chart movement of a basic expectation that corn in today's world should be worth roughly around $4 per bushel, or maybe less than that when it seemed like the globe would fall into a pandemic-related recession. The December 2022 contract, similarly, fluttered around under $4 until recently. Looking back in recent history, the new-crop futures contracts that are tasked with pricing grain in an as-yet unknown future have generally found that something within 15 cents of $4.00 has been a fair starting point before the crop is even in the ground.

What's different now -- with December 2021 corn at $4.70 and November 2021 soybeans at $12.22 -- that hasn't been the case in the past six years? The products still have roughly the same economic value to end users. Yes, there is some pre-existing drought concern ahead of planting season, sure, but isn't there always some sort of weather fretting in the spring?

No, I think it is precisely because the old-crop market is higher than it's been since 2014 that the new-crop market is finally able -- this year -- to attract traders at richer prices. Maybe it doesn't make sense, from a physical reality space-time-continuum standpoint, but humans do things all the time that don't necessarily make sense.

"Anchoring" is the word for this particular cognitive bias. It's a pitfall our treacherous brains fall into that isn't perfectly rational, leading us to rely on one numerical "anchor" when making a decision, no matter if that anchor is a reasonable place to start or not. The classic example is an auction: if the auctioneer starts at $5,000 for that old Minneapolis-Moline tractor, that starting anchor itself will influence how much you think the tractor is worth. Maybe before the auctioneer ever started talking, you would have independently judged the tractor to be worth only $1,500, but now that the anchor number is out there -- $5,000! -- well, maybe it's nicer than you realized! Something like that may be happening in the new-crop corn and soybean futures markets. Merely by seeing the front-month futures prices so high -- $5.50 for corn and $14.00 for soybeans -- traders and producers are now looking at next year's market with a new anchor and a new set of expectations.

Let's not totally discount the projections for demand to remain strong in the 2021 marketing year and for ending stocks to be tight again (especially for soybeans), but I don't think those nebulous projections alone would have been enough to radically shift the new-crop price ranges this far in advance.

The beauty of the timing of this rally, for U.S. grain producers, is that crop insurance policies will be made available next month, according to the prices that the futures markets are trading right now. The average of the February trading session closes for new-crop December corn futures (so far, as of Feb. 23) have been about $4.56 and the average closes for new-crop November soybean futures (so far) have been about $11.79. This shows a 2.59-to-1 price ratio for soybeans over corn, historically higher than usual, suggesting soybeans are receiving relatively more bullish attention than corn; to look at it another way, soybeans are relatively overpriced compared to corn, and in certain fields, they might be relatively more profitable than corn. A farmer looking at new-crop prices for 2021 production might feel relatively more motivated to lock in that soybean price more than the corn price.

Except that I suspect many farmers, seeing a relatively favorable $11.79 new crop soybean opportunity, rather than anchoring it against their own profitability, historical expectations or the soybean-to-corn price ratio, will instead "anchor" it against the $14 old-crop price and think, "Gee, $11.79 seems cheap." They should be aware that a cognitive bias is at play.

For all the grain producers who rightly appreciate this year's opportunity to put some revenue protection in place as a foundation for their 2021 marketing plan, there is one more subtlety to consider: All the lovely (upward) volatility in futures prices lately means that crop insurance premiums are likely to be higher than we've seen in recent years.

P[L1] D[0x0] M[300x250] OOP[F] ADUNIT[] T[]

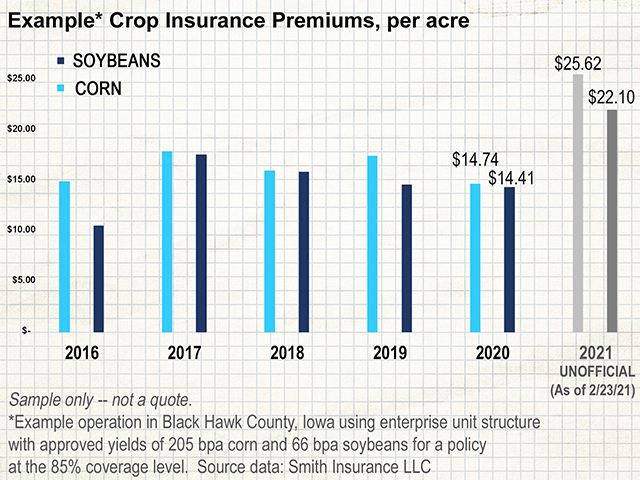

This was first pointed out to me by George Vande Vorde, an owner/agent of Smith Insurance LLC in Lamont, Iowa, www.smithinsurancellc.com, whose willingness to nerd out on the inner workings of crop insurance makes the system seem approachable. "Generally, I do not give abbreviated answers to questions relating to crop insurance," George told me, but I was able to convince him to share a clear example. Take the case of a farmer in Black Hawk County, Iowa, using an enterprise unit structure, with an approved yield around 205 bushels of corn and 66 bushels of soybeans. Last year, that farmer maybe paid crop insurance premiums about $14 per acre for coverage at the 85% coverage level. This year, because the volatility of the underlying markets makes the world less predictable for the insurance companies, premiums could be something like $25 per acre for corn and $22 per acre for soybeans.

Here's historically what that farmer's crop insurance premiums may have been (per acre):

2016 corn: $14.99

2016 soybeans: $10.61

2017 corn: $17.99

2017 soybeans: $17.63

2018 corn: $16.04

2018 soybeans: $15.94

2019 corn: $17.51

2019 soybeans: $14.68

2020 corn: $14.74

2020 soybeans: $14.41

2021 corn: $25.62

2021 soybeans: $22.10

This Iowa example is also pretty consistent with a similar example calculated by the University of Illinois Weekly Farm Economics, which can be read here: https://farmdocdaily.illinois.edu/…

The underlying math will be the same everywhere else, too -- more market volatility means more uncertainty, which means more expensive insurance.

Curiously, the "volatility" used to calculate these insurance premiums is measured only during the last five trading sessions of February. So, when November soybeans shot up 10 cents on Tuesday, on the one hand, farmers may have cheered because it bumped up the month-long average by a penny. But on the other hand, it bumped up the volatility too. In the crop insurance programs, the "volatility factor" is calculated as the implied volatility from the Black-Scholes options-pricing model, modified by a time term (sort of unannualized to reflect the growing season timeframe that the insurance policies are covering).

Earlier this month, new-crop corn volatility factor looked like it was going to be about 0.24 instead of the 0.15 it has been in more recent, calmer years. At the start of this week, the new-crop corn market's annualized implied volatility was about 0.28, which once adjusted for time becomes a volatility factor of 0.22 to be used in the crop insurance premium calculations. Anyway, long story short (or as George Vande Vorde would say, "That's the two-dollar version when maybe you wanted the 25-cent version."): This esoteric volatility math translates into real dollars out of farmers' pockets. Crop insurance premiums are going to be higher this year, perhaps as much as $10 per acre higher than last year.

But this year, with these boosted new-crop reference prices, they're going to be worth it.

Elaine Kub is the author of "Mastering the Grain Markets: How Profits Are Really Made" and can be reached at masteringthegrainmarkets@gmail.com or on Twitter @elainekub.

(c) Copyright 2021 DTN, LLC. All rights reserved.