Mexican Perspective on GMO Corn Ban

High Stakes in Mexico Plan to Ban US GMO Corn

GUADALAJARA, Mexico (DTN) -- The stakes are high for farmers on both sides of the border to solve the trade issue of whether U.S. genetically modified yellow corn will continue to be exported to Mexico.

While Mexican government officials believe their country can work toward being more self-sufficient in replacing U.S. yellow corn with its own locally grown corn, the ag community is less confident and warns of the impact of losing access to U.S. feed.

Mexico, in the current marketing year, was the top buyer of U.S. corn, with more than 5.5 million metric tons (mmt) shipped and outstanding sales of another 6.5 mmt. Mexico purchased 16.4 mmt for the market year that ended Sept. 1. This year Mexico expects to import 18 mmt.

The big question being asked in the ag sector and by farmers is where the corn will be produced if the 18 mmt is banned from the U.S.: Mexico is currently not self-sufficient in growing yellow corn and, in fact, corn producers have been switching corn production to agave production, a crop used to make tequila. Questions have also been raised about whether food prices could rise because of the decree.

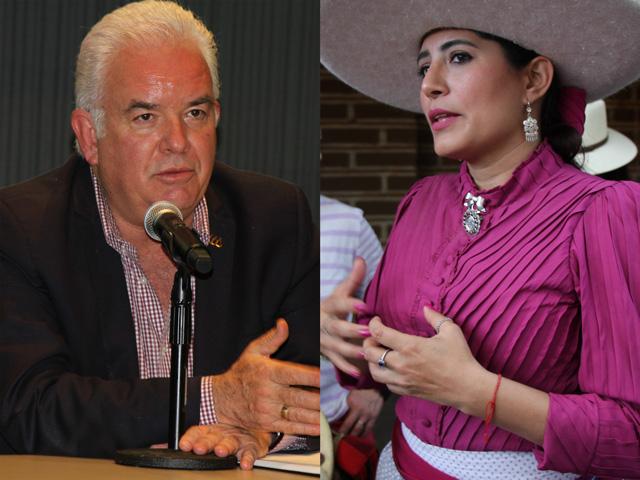

Luis Fernando Haro Encinas, director general of Mexico's National Agricultural Council, which represents 1.8 million producers, spoke at an International Federation of Agricultural Journalists meeting in Guadalajara, Mexico, on Feb. 27. He noted it is prohibited to grow genetically modified corn in Mexico.

"Nevertheless, for decades, we've been consuming genetically modified corn, which we import from the United States. So, there is no congruence here. So, we say you can consume it, but you can't produce it in your country." He said the concern is that native corn can be polluted with GM corn. Mexico has excess production of white corn, used for tortillas, but imports yellow corn.

He added, "Why do we prohibit GM corn, which is not for human consumption?" He said if there was scientific evidence that genetically modified corn causes health damage, "of course, we would be in agreement for it to be prohibited, but there's no scientific evidence, so we cannot agree for it to be prohibited in any of its forms."

As for now, "What could happen if tomorrow, we could not import genetically modified corn?" He explained that, internationally, there isn't enough non-genetically modified corn or even enough non-GM corn seed to meet market needs -- it does not exist.

"All countries -- Brazil, Argentina -- all countries produce (GM corn)," Haro said.

MEXICO BAN

While the issue of U.S. biotech corn entering Mexico has been going on for more than a year, earlier in February, the Mexico government issued a decree that was an immediate ban on the use of biotech corn for products used as food. (https://www.dtnpf.com/…)

U.S. Agriculture Secretary Tom Vilsack said last week the U.S. Trade Representative's Office will begin to have what are called SPS (sanitary and phytosanitary) conversations and consultations, and if it isn't resolved, it will move to a formal dispute settlement case through the United States-Mexico-Canada Agreement (USMCA).

The U.S. has argued that the move by Mexico was not based on a science-based and rules-based system.

Earlier this month, Mexican President Andres Manuel Lopez Obrador withdrew his earlier decree setting a 2024 date to ban glyphosate and genetically modified corn but issued a new modified stance to immediately ban the use of transgenic corn used for human food. The new decree is limited to white corn and "prohibits the use of genetically modified corn for dough and tortillas." In bold, the Mexican government stated this "does not affect trade or imports in any way, among other reasons, because Mexico is self-sufficient in the production of white corn free of transgenics."

P[L1] D[0x0] M[300x250] OOP[F] ADUNIT[] T[]

The decree adds, "What it is about is consolidating such sovereignty and food security in a central input in the culture of Mexicans." The decree also sets up new research "on the possible impacts on people's health of genetically modified corn." The decree stated such studies will be carried out with health agencies in other countries. (https://www.dtnpf.com/…)

DEPENDENT ON U.S. CORN

One of the regions watching closely what happens with the corn import decision is the state of Jalisco, in the western part of Mexico. It's Mexico's most important food supplier, producing 15% of the total value of Mexico's agri-food production -- including eggs, pork, milk, raspberries, avocados and other agricultural products -- 41.2 million tons of food annually, with a production value of more than 10.5 billion pesos -- about $500 million USD.

Jalisco state's Secretary of Agriculture and Rural Development of the Government Ana Lucia Camacho Sevilla told media at an event in Tequila, Mexico, on Feb. 28 that something good is that Mexico has time -- the decree starts in 2025 -- and the country can work to produce the corn that it needs locally, such as for feeding the livestock industry.

She doesn't believe there will be a problem growing the yellow corn they need, and Mexicans can start to build programs for local producers to grow the corn.

"We are, of course, working on these areas of sanitary and phytosanitary, in plant and animal health. And it's very important for us, not only for the international markets, but (also local markets). And of course there is a policy for constantly looking for new markets around the world," she said.

As for the U.S. threat to file a formal USMCA dispute about the Mexican ban, Camacho Sevilla said the U.S. has the right to do it, because she understands Mexico is transgressing the trade established by the USMCA treaty.

MEXICO BENEFITS FROM U.S. CORN

Haro pointed out that Mexico benefits from importing subsidized corn from the U.S. "The producers of farmers of the U.S. are subsidized. We're also importing that water with which that corn is produced, maybe that water in our own country in some regions is not enough to produce corn. And also, what we were saying, we are giving an added value to this corn, we change it, we transform it into animal protein, and we sell it as dairy or meat products or egg products."

Haro added that without evidence of genetically modified corn being damaging to health, "We'll continue importing, we have to continue importing because we don't have the production to substitute those exports, so we will continue doing it logically, and I see this as very complicated.

"Since we had decades of studies by many universities and research centers, we have no scientific evidence that genetically modified corn causes damages to health, then I see, if this is prohibited worldwide, there's going to be a food catastrophe because where will the world's population be fed from?"

He said if Mexico is unable to use GM corn, this would cause terrible damage for livestock production, including producing meat, eggs and dairy. "That would be the greatest impact, since we would not have a way to feed the livestock, feed the pigs or the poultry, if we don't have corn available, whether genetically modified or not."

HOW MUCH MORE CAN MEXICO GROW?

Mexico imports 18 mmt of genetically modified corn and currently doesn't import corn that's not genetically modified, said Haro.

Based on average production, Haro said 5 million hectares (12.3 million acres) would be needed to grow the non-GM corn the country needs under the decree. "So, we don't have a plan in the government to begin with for that to happen. There is no plan for us to be able to substitute those 18 mmt by producing it ourselves in Mexico.

"Possibly, if there is a plan, then we would have to invest in resources in seeds, which right now, there's not enough supply of seeds by the companies that produce those seeds, there's not enough supply. So that would take decades in order to achieve that," Haro said.

He also asked how feasible it would be regarding production. "How profitable would it be for all regions in our country?" He used the example of the largest, most efficient production area of the country can produce 17-18 metric tons per hectare. He said there was no capacity to increase production there, because of seasonal rainwater and climate change.

WORKING WITH OTHER COUNTRIES

Haros talked about his organization having a very good relationship with producer organizations in the U.S. and Canada, as well as with U.S. grain producers. While the corn ban is a big issue, he added there are other problems they are working on -- such as migration, labor, food safety and drugs -- that needs to be resolved for what's best for the entire region, not just one country.

He said under USMCA rules, the U.S. can have its dispute panel. "So, of course, this worries us, but we are working with the federal government, our government, to try to convince and try to share that this decision can be not very good for our country. But we are working with our counterparts in the other two countries from the United States to Mexico, and we want to avoid any commercial barrier."

"We import from the U.S. a lot of grains and oil-producing seeds. And what we believe is that we can give added value to primary production. We transform this into animal protein meats, eggs, dairy. So, we add value to these products. And that's why it's so important this trade relationship, this free trade agreement -- we import more than 40 million (metric tons) grains and oilseeds -- just corn, it's about 18 mmt."

He noted, "70% of all vegetables imported into the U.S., it's from Mexico, more than 50% of fruits imported by the U.S. is from Mexico. This is why this free trade agreement is so important, and this is why it is so important to take care of the trade relation we have with the U.S. and avoid having any unnecessary conflicts which could put at risk the trade relation."

BAYER ASKS FOR SCIENCE-BASED DECISIONS

Laura Tamayo, director for public affairs, communication and sustainability for Bayer in Mexico, said the company's point of view on the decree is that biotechnology and glyphosate have been researched, "and all the results have been that they don't have anything to do with human health, or environmentally."

Tamayo added, "So, we think, and we ask the government, that their decision must be based on science ... "We consider that this decree that had to do with glyphosate, we are worried about that, but we are working on that. So, as a company, we are willing to have all the conversations with the Mexican government, with their researchers, and to share all our information so they can make the decision, but with science as a foundation, so they can do like a macro analysis with the universities and researchers. And so, they can make this decision, but based on science, and this is the best for agricultural people and consumers."

Tamayo said Bayer is very worried because the government forbid glyphosate: "We can have very high prices and waste and economical losses, talking about Mexican producers. So, at the end of the day, we respect the Mexican government and their decisions, well, are the decisions that we are going to follow because our company respects and follows the law very closely. So, if the Mexican government says there will be no more glyphosate, so we will take that decision and ... with a lot of tools, we will follow those rules.

"But as I mentioned, (this is very worrying) for us, because we believe that according to our data, this will be very bad news for our country and will create production problems and also economical losses for producers and also for third parties -- for consumers -- because producers will charge an overprice for the loss of productivity for their crops."

(With files from DTN Ag Policy Editor Chris Clayton)

Elaine Shein can be reached at elaine.shein@dtn.com

Follow her on Twitter @elaineshein

(c) Copyright 2023 DTN, LLC. All rights reserved.