Kub's Den

Soybeans Not 'Bidding' for Acres Because They Don't Have To

Did you ever wonder why a bushel of soybeans costs $15, but a bushel of corn costs "only" $6.91? It's partly a matter of demand, i.e., what customers are willing to pay for soybean meal and soybean oil versus what they'll pay for feed corn or DDGs and ethanol. But the price ratio also represents a competition for supply. One acre of planted corn tends to yield 3.5 times as many bushels as an acre planted to soybeans (173.3 bushels per acre versus 49.5 bushels per acre). So, of course, farmers will demand more money for each bushel of soybeans to make the effort worthwhile for each acre.

Notably, however, they don't demand 3.5 times more money for a bushel of soybeans versus a bushel of corn. That's because soybeans are cheaper to grow in the first place and thus require less revenue per bushel to pay back the farmers.

Specifically, the estimated cost to produce an acre of soybeans in Iowa in 2023 will be $697, according to the latest Ag Decision Maker budgets prepared by Iowa State University Extension economist Alejandro Plastina (see https://www.extension.iastate.edu/…). Growing an acre of corn will cost almost 40% more than that at $968. Assuming these acres each yield either 59 bushels of soybeans or 202 bushels of corn, the breakeven prices turn out to be $11.82 per bushel for soybeans or $4.79 for corn.

Farmers' profitability in 2023, therefore, depends on whether they can produce the grain amid uncertain weather and whether they can sell the grain at prices higher than these costs of production. Right now, new crop cash bids in central Iowa are available around $5.50 for corn and $13.10 for soybeans, but there could be a lot of market movement before much of 2023's grain gets a price tag.

Much discussion will take place over the next few months about a "Battle for Acres" as these two commodity markets shift and change and offer various levels of profitability to the Northern Hemisphere's farmers. In the United States, the real acreage skirmish has already taken place through the month of February, when USDA's Risk Management Agency takes an average of daily new crop futures prices to set a spring reference price for the year's crop insurance policies. These policies serve as the foundational bedrock for farmers' marketing plans and insured profitability through the marketing year, so these reference prices are the data points on which many will make decisions about which crops to plant.

P[L1] D[0x0] M[300x250] OOP[F] ADUNIT[] T[]

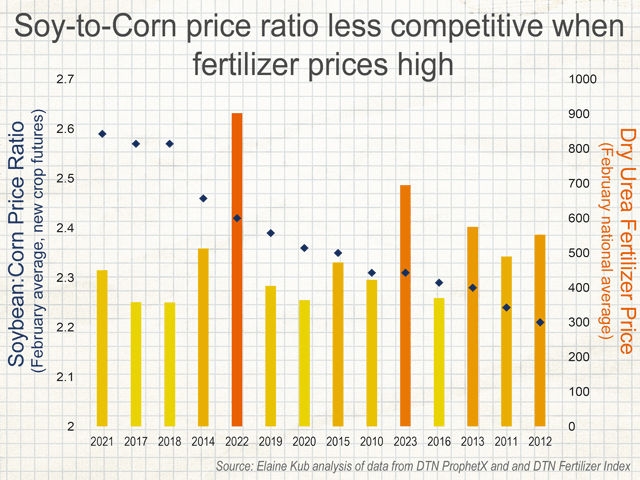

So far (with five trading sessions left in the month), it looks like the corn reference price will be around $5.95, and the soybean reference price will be around $13.76. The soybean-to-corn price ratio is historically low at only 2.31-to-1. Over the past 20 years, this relationship has averaged around 2.5-to-1. By this measure, soybeans look underpriced (according to the Iowa cost of production figures and new crop cash bids, soybeans would be less profitable per acre than corn).

However, using even slightly different assumptions about the amounts and the prices of nitrogen fertilizer applied to corn (but not typically applied to soybeans), the entire momentum of the acreage battle can change. When the University of Nebraska's Extension economists put out their 2023 Nebraska crop budgets back in October, working off fertilizer prices that were easily 15% higher than they are today, the profitability calculations definitely favored soybeans.

Some of the input costs are the same for either of the two crops -- how much a farmer pays for the land, for instance. But the major difference between the two crops' cost of production is fertilizer, which is 23% of corn's cost of production but only 15% of the soybean budget. Since soybeans are themselves a nitrogen-fixing legume, it's the additional nitrogen-based fertilizer necessary for corn that's the real sticking point: $111 per acre in the 2023 ISU estimates, or 11% of the overall cost of production.

In years when fertilizer prices are relatively low, corn production isn't as expensive. Crop prices don't need to reimburse corn farmers so generously for their planting decisions, so the new crop soybean-to-corn price ratio tends to be high. The opposite is also roughly true: When fertilizer prices are relatively high, corn must bid aggressively in the "Battle of Acres." Soybeans aren't "bidding" very hard for 2023 acres, because they don't have to. They don't require the expensive nitrogen input. Therefore, the soybean-to-corn price ratio may be low in 2023 because the soybean market can already feel assured of ample acreage.

If we knew that fertilizer prices would stay stable at today's levels through the spring, then we would dust our hands and draw our conclusion from this and move on with some confident prediction about 2023 planted acreage.

However, the fertilizer market is very volatile. Nitrogen-based fertilizers famously doubled or tripled in price from the fall of 2021 to April of 2022, but have since fallen 33% off that high. All of this has been influenced by the even-more-notoriously volatile natural gas market and, behind all that, the notoriously volatile whims of war-mongering Russia, which makes it hard to predict where it goes from here.

Furthermore, we can't say whether the fertilizer prices faced by decision-makers during planting season this May will be anything like the prices we see today, or whether those decision-makers may have already locked in their fertilizer prices 15% higher back in the fall. Whether soybeans or corn are more favorable to plant for profit depends entirely upon what price is paid for fertilizer, but it's impossible to know everyone's input costs or to generalize beyond each individual operation. Therefore, the overall favorability of soybeans versus corn in this annual "Battle for Acres" remains as uncertain as ever.

**

Comments above are for educational purposes only and are not meant as specific trade recommendations. The buying and selling of grain or grain futures or options involve substantial risk and are not suitable for everyone.

Elaine Kub, CFA is the author of "Mastering the Grain Markets: How Profits Are Really Made" and can be reached at masteringthegrainmarkets@gmail.com or on Twitter @elainekub.

(c) Copyright 2023 DTN, LLC. All rights reserved.