Strikes Reflect New Labor Paradigm

Deere, Kellogg Workers Take a Stand in Tight Labor Market

OMAHA (DTN) -- Workers and their unions in the agricultural supply chain are among the industries taking stands not seen in a generation as the country faces an unusually tight labor market and workers want more pay and benefits, especially when they were considered essential during the pandemic.

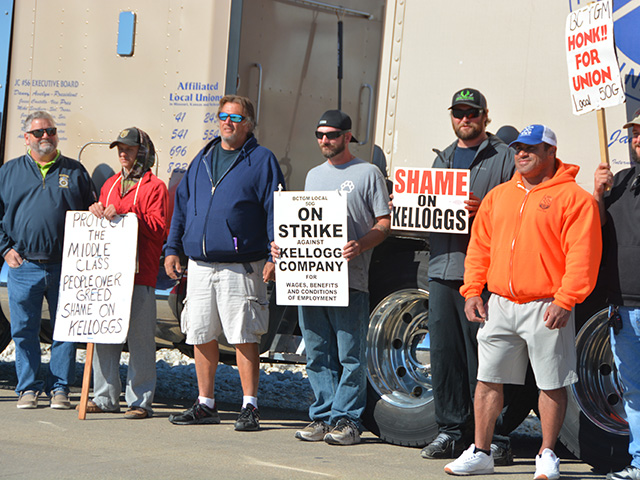

A week before the 10,000 or so Deere and Co. workers went on strike, roughly 1,400 Kellogg workers in Michigan, Nebraska, Pennsylvania and Tennessee went on strike. While Deere workers make the machinery, the Kellogg workers turn corn, wheat, oats, barley, sugar, soybean and canola oils into dozens of ready-to-eat cereals.

Talks are at a standstill between Kellogg and the Bakery, Confectionery, Tobacco Workers and Grain Millers International Union (BCTGM). Kellogg has been posting production positions for its plants on job-hunting websites such as Indeed and brought in contractors to operate the four plants involved.

"They were not willing to talk about moving off of their proposals, which is why we didn't spend any time at the table," said Dan Osborn, president of BCTGM Local 50G in Omaha, where about 480 workers have been on strike since Oct. 5. "They knew it was coming, they wanted it to come. This is their way of breaking the union."

Osborn added that union workers may have to start calling for customers at grocery stores to boycott Kellogg products. Osborn noted there are other options for cereals or snacks -- Kellogg also makes Pringles, Cheez-It crackers and Keebler cookies.

"The way we're going to win is with public support. We're going to start rolling out our boycott plan here."

Osborn said consumers might not appreciate knowing that more Kellogg cereal being sold in the U.S. is now processed in Mexico. The way to check is coding on the top of the box. KN, for instance, is Kellogg's Nebraska. The letters KX or KQ mean that cereal was processed in Mexico.

"Sending our grains down to Mexico to be turned into cereal to be turned around and brought back up here, that ought to be a bipartisan issue. They are starting to bring it up here in droves to keep their shelves full," Osborn said. "That's Mexican cereal with no FDA or OSHA oversight."

PANDEMIC SPARKS WORKER GROUNDSWELL

P[L1] D[0x0] M[300x250] OOP[F] ADUNIT[] T[]

Paul Iversen, a former labor attorney who is now a professor for the University of Iowa's Labor Center, said both the Deere and Kellogg strikes are part of a larger worker groundswell that stems from the pandemic. In both of those companies, workers are pushing back against company demands they might have accepted before the pandemic.

"It's kind of this view that workers have to assert themselves because employers -- big corporations -- don't really care about their workers," Iversen said.

The unemployment rate nationally is at 4.8%, but there are 5 million fewer people working nationally than in February 2020, just before the pandemic lockdowns, the New York Times reported (https://www.nytimes.com/…). The issue isn't just Baby Boomers retiring -- there is a smaller percentage of people ages 25-54 in the labor force, according to the New York Times report.

While companies are now expressing concerns about labor needs, Iversen said workers and their unions have become more aggressive this year in demanding higher pay and better benefits, especially as their parent companies not only weathered 2020, but came out of the pandemic more profitable.

"The only thing workers can do to put pressure on employers to increase wages is to withhold their services and say, 'I'm just not going to sell it for that,'" Iversen said, referring to the value workers are willing to place on selling their labor to companies.

Osborn noted Kellogg profited during the pandemic. Kellogg Co. reported $1.76 billion operating profit in 2020, about 12.8% of net sales, the highest level the company has shown in recent years.

"And that is what they're turning around to do is refuse to negotiate with us and instead go out and advertise for replacement workers," Osborn said. "The status as far as the negotiating table goes, it's radio silence as they continue on with their plans to operate the plant without us."

Kellogg referred questions from DTN to its website on the talks with statements released Oct. 12. There, the company refutes the idea that the company is threatening to move more of its processing capacity to Mexico. Kris Bahner, a spokeswoman for the company, states on the website that Kellogg is ready, willing and able to continue negotiations at any time.

"In the meantime, we have a responsibility to our business, customers and consumers to run our plants, despite the strike. We are continuing operations with other resources and hope that we can reach an agreement soon."

OPPOSITION TO TIERED BENEFITS SYSTEM

The unions for Deere and Kellogg workers also all went on strike in opposition to some form of tiered wage or benefits system that would treat younger or future employees differently. Both Deere and Kellogg unions balked in pension changes for future employees.

"At this point, we have to finally dig in. I believe this is something that has been going on really across the board for years as workers and labor continue to get less as companies continue to take more," Osborn said.

The Deere strike is its first since 1986, while Kellogg workers had not gone on strike since 1972. Deere and Kellogg workers were considered essential early in the pandemic.

"As frontline workers, feeding the front lines, feeding America, there was a pride to that. We embraced all of that," Trevor Bidelman, the BCTGM Local 3G president from Battle Creek, Michigan, said in an interview with Yahoo. "The company was calling us heroes. They were thanking us for everything we did, and less than 12 months later, that hero become a zero just a real quick switch of the letter."

Iverson associated the strikes with farmers pushing for the "right to repair" their software-driven machinery, or livestock producers moving to form their own processing facility because a few packers dominate the market. "We see more opinions that corporations are getting too far removed from the people that have built them up to where they are," Iverson said.

Labor issues are playing out in a lot of ways right now. Just last week, a coalition of agricultural groups wrote Transportation Secretary Pete Buttigieg about supply chain challenges. Labor was the most pressing issue, groups stated. Read more about that here: https://www.dtnpf.com/….

States are responding to tight labor markets in different ways. Iowa Gov. Kim Reynolds on Thursday, with the state sitting at 4% unemployment, issued new requirements for unemployed people starting next year to double the number of job searches required to draw unemployment. Nebraska Gov. Pete Ricketts on Friday issued a news release touting Nebraska's 2% unemployment rate is the lowest in the country, and Nebraska has the third-highest labor-force participation rate at 68.4%, behind only North and South Dakota.

Chris Clayton can be reached at Chris.Clayton@dtn.com

Follow him on Twitter @ChrisClaytonDTN

(c) Copyright 2021 DTN, LLC. All rights reserved.